Route Develpment -The First Rule of Dig Club

I had broken the First Rule of Dig Club. The First Rule of Dig Club is: you do not talk about Dig Club. The First Rule prevents the public from seeing and reacting to the removal of vegetation and therefore maintains their naïve ideas about the origin of rock climbs. It also keeps Diggers in the closet, equally naïve about how to develop a route of quality.

Fingers curl over the top edge of a dirt mound. Hands cinch down. My legs straighten. It was a tug of war, me versus the roots that anchor the mud mound to the cliff. I pull. The roots pull back. My knees bend in defeat, then push against the wall. I pull again, halfheartedly. I slump. “More cutting,” I gasp between breaths. The red light of the video camera blinks and turns dark. To share my excitement about the new terrain in Squamish, I posted the video online.

“Take down the video, post your topo when your route is finished, and keep quiet about it,” a member of the Establishment muttered. Why was he offended? I was only trying to make Squamish better.

I had broken the First Rule of Dig Club. The First Rule of Dig Club is: you do not talk about Dig Club. The First Rule prevents the public from seeing and reacting to the removal of vegetation and therefore maintains their naïve ideas about the origin of rock climbs. It also keeps Diggers in the closet, equally naïve about how to develop a route of quality.

Something Clicked

Hoping to give something back to the Squamish community, I developed my first climb in 2003. After a climb up Birds of Prey 5.10b, a partner and I walked along the top of the cliff for 50m, wrapped a sling around a tree, and explored on rappel. The cleaner features seemed to mostly link together. It looked good to me. In seven days of work, I dug and scrubbed the route then spread the word. It was time for the community to reap the benefit of Optimus Prime 5.10c.

“Have you climbed Optimus yet?” I asked a friend. He paused. “No. We went up to try. We looked around and couldn’t find the start. So we climbed Birds of Prey instead.” I had hoped he’d climb it and like it. I felt disappointed. Over the coming years, the route filled in with needles and began to regrow. Optimus Prime was both my favorite Transformer as a child and a climbing route from my Digging infancy.

Optimus starts up an obscure chimney. From the base, you can’t see more than 10 feet of the climb. Everything else you see is dirty. In hindsight, I can see why my friend wasn’t drawn to it. While developing Optimus, I thought more about connecting features and not nearly enough about the fresh user’s experience. Something clicked. What would it be like to try this climb for the first time?

“So you drilled the bolts?”

Fast-forward eight years. I saunter up to the base of the Shannon Wall and tilt my head back. The falls hiss white noise and mist tourists. A pair of climbers disappears behind the horizon 100m above. Another party passes hardware back and forth at the second belay. Cams and biners clatter on a chap’s harness as he scuttles down the descent trail to the base. “How was it?” I ask. Two weeks earlier, I had opened this five-pitch 5.8 route called Skywalker. Gripped reported, the Squamish Climbing website tweeted, Sonnie Trotter blogged and Skywalker caught fire.

Within two weeks, the route had line-ups sometimes four hours deep. Anticipation of this moment-hearing the rolling boil of enthusiasm in the voice of a stranger-kept me digging through the long, clammy winter. Equipped with a mattock, scrub brushes, pliers, a sidewalk crack scraper and lessons from 60-odd pitches of route development in the intervening years, I had finally nailed it. I had an instant classic and Squamish was the better for it.

“So you drilled the bolts?” he queried. “Well, yes, but…” What he could see is the dot of the ‘i’-the bolts. What he couldn’t see was the full signature, the metric tons of composting organics in the forest below.

The climbing public loved the result. Varied face, crack, and slab climbing opens the adventure on the first pitch. An acute corner on the second pitch demands either technique or stamina. Exposed finger-locking on the third pitch ramp is “like licking chocolate off ice cream,” said gent on his second trip up the climb that month. Standing at the belay before the Skywalker Traverse pitch, you look rightward at a vertical wall intersecting a slab that rolls off below.

The climbing looks sloping and exposed. Your partner places a few pieces then disappears around a corner as you pay out rope. Your mind begins to drift. That looks slippery and scary. A tiny plaque under a bolt hanger whispers encouragement: “May the force be with you.” After the anxiety comes a release. The climbing is easier than you expected. You reach the top of the wall and turn around. Howe Sound stretches 180 degrees below. The sun retreats toward the mountains on the opposite side. Life is good.

After the route had been cleaned, Martin Chabot in the 5.8 crux corner of Skywalker during the first ascent.

After the route had been cleaned, Martin Chabot in the 5.8 crux corner of Skywalker during the first ascent.

Skywalker was a hit. If the numbers and words are any indication, the public decidedly loved the result. Over a decade of trying, I had finally stumbled upon the secret ingredients to developing popular routes. What should I do with these ingredients? As I prepare to leave Squamish for a psychology professor post at the University of Winnipeg, do I take my stories with me? Or do I leave them in Squamish where they might do some more good? Do route developers want to know? Do climbers?

How would they feel if they saw my mattock tearing into the triangular column of dirt that filled the corner that is now the finger locking crux second pitch on Skywalker? What kind of taste would it leave if they saw me hacking at a tree then pinching the roots poking on the chocolate-on-ice-cream pitch? Would they pause if they watched me felling live trees off the Skywalker Traverse pitch?

Fear in Between

When it comes to route development, climbers cherish the after; the splitter cracks, the clean slabs, the crisp edges. Before Diedre 5.8 became what it is today, the corner was filled with earthy, native plant life. The before and the after look and feel good to us.

“Watch this!” I click the sideways triangle and a video animates. A figure cloaked in yellow raingear hunches over. His chainsaw growls. The treetop quivers, then wavers, then arcs toward the ground. I look at my friend for resonant excitement. A new climb is on the way.

“That’s sad.”

I am taken aback and offended. That tree was growing out a climb that I was developing for the greater good. It was the climb or the tree. The tree had to go. “What is sad?” I asked.

“That the tree had to die for our enjoyment.” What happens in between before and after stoked sadness and revulsion. Is this aversive feeling the motivation for the First Rule?

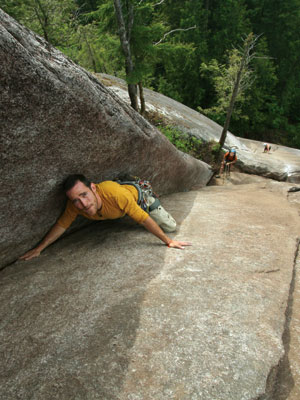

The author in a tug of war with a dirt mound during the development of Milk Road on Tantalus Wall

The author in a tug of war with a dirt mound during the development of Milk Road on Tantalus Wall

I wonder if climbing is like eating hamburgers. Lots of people love eating burgers. Lots of people love climbing. The after is good.

Lots of people think cows are cute (from a distance). Lots of people find native vegetation endearing, grounding. The before is good too.

Think of what happens in between. Everyone knows that a cow has to die for it to become hamburgers. But knowing doesn’t make it feel any better. Everyone eats dead things every day. Even vegetarians. Lettuce lives. And everyone who has walked on a trail anywhere near Squamish has walked over a spot where a tree was cut down. We all know it. We’d rather just not think about it.

One way I could react is to call my critics hypocrites. I could say, “don’t eat what you won’t kill. And keep your morals off my mattock and broom.” Another way to react is to get excited by the ‘nonsense’. Psychology has taught me that oddities are opportunities for learning. People are complicated. Climbers are just as complicated.

And that’s OK. That’s better than OK. That’s fascinating.

One Layer Beneath the Surface

Branches were everywhere. My saw swung wildly, making quick work. While developing the Skywalker descent trail, the saw’s efficiency turned reckless. One hand lost track of the other. Blood dripped out of seven small punctures in my left wrist. I stumbled backwards, away from the edge of the wall and leaned against a boulder. “Sit down. Don’t pass out. You are on an exposed ledge.”

Having cut through a tendon completely, I required emergency surgery. I wanted the surgeon to put me under. I don’t want to see. I don’t want to know. My surgeon chose to use local anesthetic. I was awake throughout. The injury I was OK with. And a splinted wrist would be OK too. My fear was of the between. As she sat down with my left wrist, I turned my head to the right. Think of something else. Think of Jenny. Think of Peru. She has a scalpel. Oh gosh.

The scalpel sliced into my wrist. It felt like she was softly drawing on my wrist with a pen. The anesthetic was working. It didn’t hurt.

She offered that I take a look. Fear and disgust swept over me again. “No thanks,” I returned as my Mountain Man façade went for a hike. She encouraged me again. I finally agreed. Then something strange happened.

I lifted my head to have a look. An intact tendon looked like a yellow rubber band, only thicker. The severed tendon looked like the end of a strand of linguine. I expected disgust. Instead, I was fascinated. My mind simulated what it would feel like to look inside of my wrist. It turned out to be dead wrong. The in between was nothing like what I expected it to be.

I wonder if the First Rule is a product of the same paranoid fear produced by our complex, rusty mental simulator. Maybe The Establishment thinks that talking about Digging will make people feel disgusted. In reality, might people actually be intrigued?

George Corbett working a come-along to pull a resilient cedar stump out of the first pitch of Rambles. Along with a sledgehammer and six-foor crowbar, the stump eventually gave way.

Where is the Conflict?

Two weeks after surgery, with arm in splint, a friend joined me to finish the trail. I directed and he cut. I motioned at a small cedar in the middle of the trail. He started cutting. Then another strange thing happened. A voice yelled “No!” The tree was dying and someone was protesting. That someone was a voice inside my own head.

Just a minute before, I had made the decision to chop it down. And now I was internally revolting. What was happening? Why had my feelings changed so quickly? If this was happening in me, a Digger myself, then maybe the First Rule isn’t only the result of shoddy forecasting and fear of what we don’t know. Maybe it’s something even more fundamentally human-a conflict within each of us.

During my studies in psychology, I’ve come across a lesson over and over. When people try to navigate important decisions, different sentiments arise at the same time. Sometimes emotions lead us one direction. Harm to a living things (like cows and tree) summons empathy and says “stop”. And sometimes reason leads us the other direction. Maybe removing a few trees in a healthy ecosystem or humanely slaughtering a cow is acceptable as long as it produces a good climb or tasty nourishment.

This conflict between ‘yes’ and ‘no’ makes us feel rotten. Not talking about it might make us feel better at the time. But it creates a new problem: the First Rule of Dig Club. The First Rule kept me in the dark when I cut my teeth on Optimus Prime.

Lessons Learned

Squamish, I leave you with four lessons that I’ve learned.

Less is More.

I haven’t done a systematic study about it, but my hunch is that five times more people climb 5.9 than 5.10. And five times more people climb 5.8 than 5.9. And so on. As my route development goal morphed into the greatest good for the greatest number, lower grades became the objective. Lesser grades mean more traffic. Almost everyone loves a 5-pitch 5.8.

More is More.

Inviting routes tend to be low-angle. Low angle rock collect falling needles and dirt more so than steeper terrain. Some of the best features are buried under years of debris. Skywalker was a jungle in 2010. Traffic keeps popular routes clean. Unpopular routes overgrow. This sets up a dilemma, a gamble. Digging deep is more work but can have bigger pay-off. More popular routes generally require more digging. More is more. Research many lines. Find a fantastic one and bet it all.

With their eyes.

On a morning commute from Squamish to Vancouver on Highway 99, out your front windshield, at the base of the Apron, is a freshly scrubbed diagonal crack. You are looking at Rambles, a 5.8 route that runs four pitches. The fact that it thrusts itself into your view was no accident. I want my climbs to pop out at you from the road or a trail. I invest a huge amount into making approaches easy to find and intuitive to follow. From the base of the climb, I want you to be able to see most of the climb. From each belay, I want you to see the next pitch clearly. I want the climb to be so intuitive that you don’t need a topo to follow it. People climb with their eyes.

Get in their head.

While developing a route, think about the route from the perspective of a new climber. Go to every single spot on the climb and look up. Look down. Look left. Look right. What do you see? How does it look? Is it clean? Is it obvious where to go next? Is what you see inviting? Be honest with yourself. A dirt streak beside the route but within the visual range is an eyesore and affects how the climber feels. The underside of little overlaps or overhangs may not affect the climbing directly but they are highly visible from below. A root sticking out of a crack looks like death. If something is ugly, make it beautiful. If you are on one of my climbs and experience the surroundings in a positive way, that experience was the product of deliberate choices. You’ll likely never know about all the unpleasant experiences you never had.

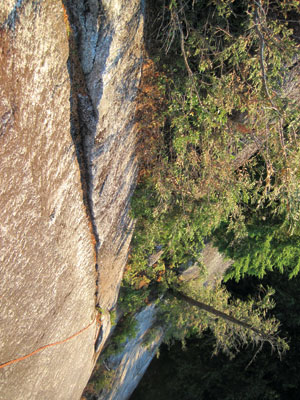

Before work on pitch two (The Flume) of Skywalker in September 2010, on the first exploration of the wall

Before work on pitch two (The Flume) of Skywalker in September 2010, on the first exploration of the wall

My Hope

All of these ingredients require effort. On Optimus Prime, I wanted to but didn’t know how to apply myself. The result was not unlike that of many new climbs that went the way of the moss. My hope is that future Diggers will rely on the collective experience of Diggers past. My hope is that Diggers will share their stories openly, learn from each other the easy way and feel appreciated for the investment they make in their community.

Farewell, Squamish. May the force be with you.

Jeremy Frimer is climber and route developer who has recently left Squamish for a post in the department of Psychology at the University of Winnipeg.