New Troll Wall Film, and a Canadian’s Story About a Norway Climbing Trip

Watch a new film with Pete Whittaker, and read a story by Ontario climber Tom Valis about a trip to the famous big wall

The Troll Wall is one of Europe’s most famous big walls, with a history that dates back decades. The wall is notoriously loose, with huge sections collapsing every few years.

In 1998, a portion of the 1965 British Route fell down. The rockfall measured 2.5 on the Richter scale. Local climber Sindre Saether has left a significant mark on the wall, being the first to free aid lines which were previously thought unfreeable.

Top trad climber Pete Whittaker has just released a film about an ascent of the wall that he made with Mari Augusta Salvesen. Scroll down for a story that first appeared in Gripped in 2012 by Ontario climber Tom Valis about a trip to Norway and the Troll Wall.

Troll Wall by Tom Valis

There were two grading systems that mattered when I started climbing. One real, the other imagined. There was the decimal system that had found its way from Yosemite Valley and Eldorado Canyon to the crags of Southern Ontario. It’s pronouncements of success or failure a measure of, above all else, talent. The double digit end of the scale provided entry into the ranks of hard men: willful violators of social expectations that I had, by then, occasionally met.

But, as trips to the library made me aware, a second, Roman numeral grading system indicated how committed you were to the game. I had to guess at what a route more committing than grade III was like, since that was the grade of the longest climb I could drive to. Was a long-weekend of climbing at the 100m tall Bon Echo the equivalent of a grade IV in the Sierras? What about winter camping combined with a season at Rattlesnake Point?

The equipment and methods necessary for climbing routes with numerals V and VI, were equally speculative. How many ropes were required? One at Rattlesnake, two at Bon Echo: so three for bigger things? The thought of managing three ropes twenty or thirty pitches up seemed tricky. But what if one got cut, or slid away? Having two left would offer a reassuring level of redundancy and a chance to retreat if things got really bad.

This calculus of consequence continued until I found myself in a climbing shop in Stockholm in 1984 with enough money to buy two ropes to add to the one that I had started with two years before. The manager asked me if I preferred a supple, easy handling rope, or one that was stiffer and more durable. There seemed no obvious answer, as I had never climbed anything longer than the 100m-long five pitch Ottawa Route 5.8 at Bon Echo. “I’ll take one of each,” I said, thinking to hedge my bets and not realizing you bought double-nines as a set. I figured I’d double my rack with whomever I’d find to climb with.

I took a borrowed Renault in mid-August on the road to Norway from the familiar lakes and forests of central Sweden. By rights, I should have been heading past Thunder Bay on my way to the Rockies, but that trip was another year away. Sweden had been my summer home since childhood, and so the closest mountains lay along the North Sea coast rather than the western cordillera. Broad valleys gave way to narrower ones, rain was never absent, and the distances between towns became greater. Cinnamon buns and coffee were the necessities of every rest stop.

A morning later, I turned off the engine at a gravel parking lot frequented by local fishermen and asked for directions to the base to the Trollveggen (Troll Wall). No angler was quite sure, but they had seen some English visitors in the area. Sure enough, an hour later, some appeared from the adjacent boulder field looking rather wet and offered me directions to their base camp. Apparently, they had been here a week waiting out the rain. And one of them, Simon, was looking for a partner.

It was as if I’d just fallen into the pages of a Chris Bonington hardcover book: plastic sheeting rigged to make a cooking shelter, route discussions, gear sorting and musings about events taking place in France with bolts. Brew-ups and biscuits punctuated each day as a steady downpour prevented us from actually seeing the 5,000 foot face above our camp. From the discussions of strategy and tactics, I’d gathered that two ropes would suffice and that sleeping ledges would appear. I made no mention of a third rope.

Simon and I did a warm-up climb on one of the gun-metal sides of the Romsdal valley. I recall the following exchange some pitches up, after having led a sustained stretch and come to a belay. Water was coursing down the crack system we were following:

“Man, that was hard, my pants are soaked.”

“It’s always easier seconding, only my trousers got wet.”

It quickly became apparent that the this style of climbing lay somewhere between the strict adherence to free climbing I knew on the Escarpment and the occult world of aid climbing that I’d read about in the Chouinard catalogue. As the Brits told one another: it was matter of getting on with it.

“No matter what,” was left unsaid.

Going into town was a daily ritual. The most important thing was to look at the self-explanatory weather forecast in the local tabloid: closed umbrellas, half-open umbrellas, or open umbrellas (as was usually the case). There was also the bookstore, from which we sketched out the route description on a piece of paper from the book, Walks and Climbs in Romsdal. A rather unassuming title, I thought. Why buy it, when there was only one route in it that mattered?

The day the tabloid announced a succession of closed umbrellas all along the Norweigan coast, there was not a moment to waste. Not that there was much packing to do: a litre of water, some bread and cheese, a hat, a recently acquired shell and a bivy sac. That was pretty much it before setting off in jeans and the new “fire boots” (Boreal Fires) that had come on the market that summer promising levels of adhesion usually found only in Formula 1racing.

On our way up the approach slabs we were stopped by some sort of ice hose. Given that Simon was from Devon (where it never snows) he got a free pass. Getting up this sentinel in search of a north wall seemed my responsibility. “No matter what” become my mantra as I found some sharp looking rocks and began step cutting while recalling Conrad Kain’s heroics on the Mount Robson. The pointed toes of my shoes worked remarkably well as rubber monopoints. I kept telling myself to keep my weight over them.

After a few pitches we reached the first bivy where we found a jar with notes. This was our final chance to flee before being judged by geologic forces that had stacked blocks of gneiss above us. We wrote our names and respective countries and screwed the lid. Perhaps the umbrellas would reopen open tomorrow and we could claim a sporting defeat before heading to the pub.

Morning arrived with Nordic summer radiance, lighting every possible corrugation of the wall’s mammoth geometry. A sense of resolute action took hold of us as we climbed up the The Rimmon Route VI 5.10 900 m, reassured by old pins pins and decaying slings not unlike those I had gotten to know above Lake Mazinaw in Ontario. By noon, our efforts got us to the base of the so called Great Wall, four pitches of cleaved angular steepness beyond which retreat was outside of our rigging abilities. Between us and the Greatness was strung some agricultural rope left behind by a Polish winter expedition a few years back. Using it would save us a pitch or two of downclimbing. Recalling that speed is safety from the Canadian Rockies guidebook (which I owned, but hadn’t actually used) I clipped in to the rope while tightly holding a #1 Friend that I could place one got to the other side. Both of us across, we felt we had done the business with fate. There was more to do: swapping leads infused with twenty-something strength and singing silly love songs to shake off the belief that each hanging stance would be our last. At the end of those four pitches I discovered that a soft, supple rope will wind its way around a stiffer one, necessitating frequent (and somewhat terrifying) untying. I also realized that a liter of water is good for about a thousand feet of climbing and that jeans fray in the absence of free-climbing etiquette.

Above the Great Wall we encountered a pitch called The Black Cleft. Neither of us, in our combined months of climbing experience had ever climbed something so brutish, dank, and unprotected. And more past that, until dusk found us on a small ledge with just enough wet moss to suck some water out to quell our thirsts.

Another bright morning and off we went, becoming self styled masters of the corner layback, following a route that was the considered a masterpiece of route finding at the time of its first ascent in 1965. Pitch followed pitch, the demin tore at both knees, the occasional bouldery move appeared, clouds rolled in, and before long we had little sense of where we were. In those hours, the serenity of purpose, so often described in climbing writing, took hold of our beings. All peripheral thoughts were dislodged, all sensation directed to the tips of our fingers. No awareness of cold or dampness, no words spoken between us. All a great experience if nothing went wrong. And nothing did until I saw Simon in outlined against a jagged cirque. It was the exact composition of the black and white Troll harness ad I’d seen in British Mountain magazine. This had to be the top, I yelled. Sure enough, it was and we shook hands atop the highest wall in Europe. Rubble, fog, and the realization that there was a descent: “Did you write it down? ”

“No, I thought you did.”

We should have been more thorough at the bookstore.

The sound of waterfalls in the distance. Boulder fields with uncertain gradients. The chaotic swirl of fog revealing snow patches. No sense of direction as darkness fell and we spent another night out. No sun to greet us the next day, Fire boots blowing out, seeking purchase on wet lichen, we followed a blind gradient, hoping to avoid the hydrographic abyss. With our harnessess back on, we forded streams whose currents were too fast for our liking. Hours of this passed until we heard the sound of a car, and then another. The sense of an ending.

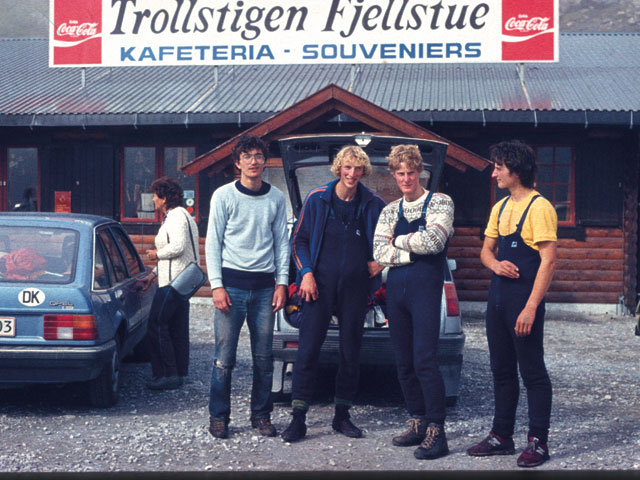

All that remained was to get to the warmth of a roadside snack shop, catch a ride down valley, and find our way to camp. After the fact bravado, the splitting of gear, the arctic sun granting us a few more hours of sun before it was time to say good bye.

The drive back across the Norwegian mountains to the Swedish border was a coffee fueled coda through midnight, as rain overpowered the wipers. A hallucinatory co-pilot convinced me that I could rely entirely on the dashboard instruments to steer. Lights appeared and disappeared in the darkness as cities in flight. At some point, I had the sense to pull over and fall asleep. A final bivy before the mountains evaporated with morning fog. Soon I would be back to the flatness of lakes and the reassurance of pine forests. – Tom Valis is a regular contributor and book reviewer for Gripped. This story was written for the summer 2012 issue of Gripped.