Mountaineer Dee Molenaar Dies at 101 Years Old

He was a member of the famous 1953 American K2 expedition

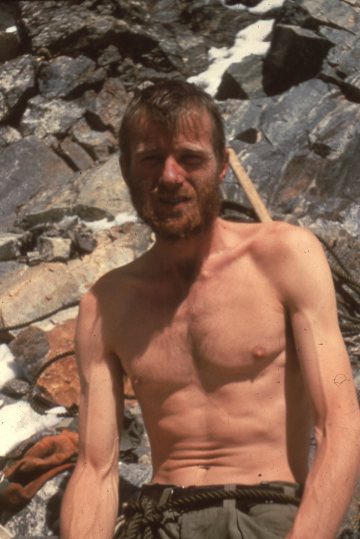

Legendary American mountaineer and artist Dee Molenaar passed away this week. He was 101 years old. He was known for having climbed Mount Rainier, where he guided over half-a-century ago, over 50 times.

Born to Dutch immigrants in June 1918, Molenaar spent much of his climbing the mountains of southern California. He soon ventured north to explore the glaciated peaks of the Pacific Northwest, where he served as a park ranger and mountain guide at Mount Rainier National Park.

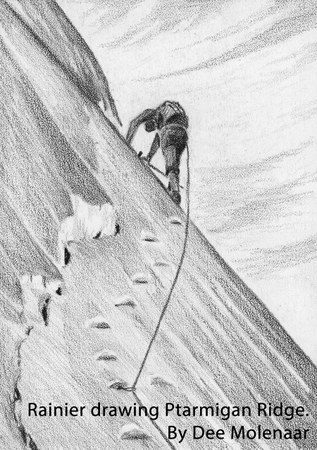

He wrote a book called The Challenge of Rainier, considered by many to be the definitive history on the mountain. Watercolors by Molenaar appeared throughout his book, in journals and in Mountaineering: The Freedom of the Hills.

In the Northwest Mountaineering Journal, Molenaar talked about his early climbing days: The event that shaped my destiny more than any other was my visit to Mount Rainier in the summer of 1939, with my brother Cornelius (known as “K”) and two Los Angeles friends. Arriving at the Paradise Ranger Station in my 1928 Model A Ford, we sought permission to climb the mountain without hiring guides.

After much questioning about our experience in mountain climbing (“We’ve just done Lassen, Shasta and Hood”), we were issued the required permit for a one-dollar fee. We promptly visited the nearby Guide House to check on the rental price of equipment. There we met Clark Schurman, Chief Guide of the Rainier National Park Company (RNPCo). Little did I realize that meeting this intense little man would be the most providential contact of my life.

Schurman noted our homemade ice axes and smooth soled, knee-length boots—better suited for hiking the Mojave Desert of our native California—and said he’d rent us what we needed at half the normal price. Somehow he seemed to take a liking to us, perhaps through empathy for our combined enthusiasm and obvious lack of much experience climbing these glacier-clad volcanoes.

Fortunately for us, the weather did not cooperate and we were stormed off the mountain at 11,000 feet by a massive cloud cap on the summit.

We continued our trip around the western U.S., and upon returning to L.A. I sent Schurman a small watercolor of the mountain, asking if he remembered the four poorly-equipped kids in the Model A Ford. Schurman responded immediately and wondered what I was doing with my life. When I said I was milking cows on my uncle’s dairy he suggested that I go to college and study art and come to work for him the next summer.

Somehow the old scoutmaster had perceived in my thank-you note and painting a youth who would fit into his world of mountains. He took a chance and invited me to guide on the mountain, starting in the summer of 1940. Following World War II and several years earning a geology degree at the University of Washington, the door was opened to my serving in the Park Service at Mount Rainier and eventually a career in geology.

During World War II, he served in the U.S. Coast Guard in the Aleutians and Western Pacific. In 1950, he earned a degree in geology at the University of Washington and served as civilian adviser in the Army’s Mountain & Cold Weather Training Command at Camp Hale, Colorado. His career in geology took him across the western U.S. and he retired from the U.S. Geological Survey in 1983.

He climbed peaks throughout the U.S., Canada, Alaska, Himalayas, New Zealand and Antarctica. In Alaska, he made the second ascent of Mount St. Elias in 1946. Nearly 20 years later, he made the first ascent of Mount Kennedy in Yukon, next to Sen. Robert. F. Kennedy, which they named for president John F. Kennedy.

He was also a member of the Mountain Rescue and Safety Council, a group formed by Mountaineers members which eventually grew into the national Mountain Rescue Association. Molenaar was a member of The Mountaineers for 79 years. He received an Honorary Mountaineers award in the early 1990s and honoured with the Mountaineers Lifetime Achievement Award in 2017.

In Mountaineer magazine in 2017, Mary Hsue talked about his time with Moleneer: “A musty odor wafts up as we descend the narrow, creaky staircase into the basement. I’m following a surefooted 92-year-old man down the steps and into a cold, well-lit room. Paint, brushes, books, and stacks of papers cover every available surface. ‘It’s here,’ he says as he gestures me to follow him towards a large table.

“Under a cloth-covered canvas is a portfolio that contains a watercolor he painted at 26,000 feet.’ I think I can get in the Guinness Book of World records for this,’ he says proudly as he carefully hands me the painting. ‘I painted it in our tent during the storm.’ He’s referring to the storm on the American Karakoram Expedition to K2 that gained fame not for summiting the peak but for an act of heroism and a single belay, or as mountaineers around the world know it, ‘the belay.'”

Molenaar was part of a famous 1953 fall during an American attempt on K2 known as “the belay” that saw six climbers saved to one climber’s ice axe. On K2, Molenaar had also painted the world’s highest watercolour.

Back in the early 1950s, few attempts and only two successful climbs of 8,000-meter peaks had been made and high altitude sickness wasn’t understood. Dr. Charles Houston, Dee Molenaar, Art Gilkey, Bob Craig, Tony Streather, George Bell, Bob Bates and Pete Schoening were the team on K2. They reached nearly 26,000 feet but were trapped in a violent storm.

After nine days, Gilkey collapsed and Houston determined that he had blood clots in his left calf, a condition called thrombophlebitis. If a clot broke loose and reached his lungs, it could be fatal. His only chance was evacuation from camp VIII.

Gilkey was wrapped in a sleeping bag and tent and the others tried to lower him. Reaching 24,700 feet on unknown terrain down a ridge, they stopped at the top of a steep gully leading to camp VII. Schoening was lowering Gilkey in the makeshift stretcher, using his ice ax as an anchor. The rope ran over the boulder, around the ax, and around his waist and hip to his hand.

Craig had moved to Camp VII to set up two tents. Five other climbers were divided among three ropes, two of which were tied to Gilkey. All were exhausted by effort and altitude when Bell slipped. He pulled Streather down onto the rope between Houston and Bates, knocking them off their feet, then Streather hit Molenaar. As they careened toward a cliff, their weight came across Gilkey and the rope to Schoening.

Schoening stood his ground. Somehow he managed to hold all six climbers and stop the fall.

Houston was knocked out, three others injured. Craig, Bates, and Streather anchored Gilkey on the slope and helped set up the tents to regroup. When two returned for Gilkey, he was gone, apparently swept away in an avalanche.

What remains of the story is the tale of closeness and solidarity in great danger. The stuff of great legends. Houston concluded, “We all returned the very best of friends, and we remain the best of friends to this day.”