A PhD in the School of Rock and Snow

There is an old saying "those who cannot do, teach." The ACMG is an exception; you have to be able to do both.

For some, a professional career starts with an academic degree and takes patience, hard work, a blinding obsession and years of education. Becoming an Association of Canadian Mountain Guides, guide takes a similar amount of work. Instructors and guides work tirelessly to achieve a standard with which they can confidently lead the public in rock and alpine environments. This devotion is why the ACMG certification is so revered and those who have achieved it are so dependable. Now it’s time to find out if you have what it takes.

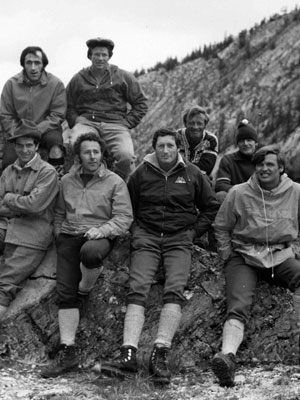

With the wind whistling overhead and thousands of metres of exposure on either side, you can only imagine what the small team of cowboys were thinking when they were guided and gently teased, across the north ridge of Lake Louise’s Mount Victoria. “Stand up, you won’t bump your head boys, it’s only the sky…” was the taunting line from Walter Perren, the knowledgeable Swiss-born guide who led them. This was to be the first team of Canadian mountain guides.

European-born guides like Perren worked to maintain standards of professionalism and to carry out rescues, but they received little help on rescues from the park wardens. “If I can’t ride there, I ain’t going,” said one ranger. It took many more years and a few more tragedies before Parks Canada finally took Perren’s suggestion for a sound and rigorous standard of mountain rescue seriously.

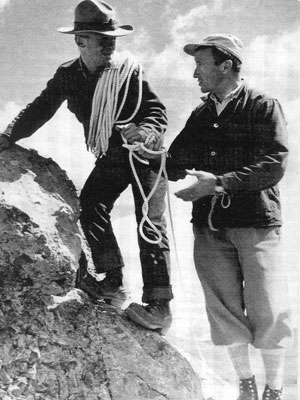

(below: Lloyd Gallagher teaaching a client to rappel in 1967)

In 1963, his idea came into fruition as the Association of Canadian Mountain Guides (ACMG). The founding members were Hans Gmoser, Eric Lomas, Peter Fuhrmann, Brian Greenwood, Willi Pfisterer, Dick Lofthouse, Leo Grillmair and Heinz Kahl. Parks Canada hired Perren to teach their staff mountain skills. Perren changed them from cowboys to mountaineers, roping them up and giving them the competence to operate above the tree line. The certifications eventually spread from Alberta into British Columbia, becoming the governing standard in the west. The ACMG quickly became the first non-European member of the IFMGA (International Federation of Mountain Guides Association). A code of conduct was developed to ensure the safety, health and welfare of clients and the public.

The Highest Standard Possible

“Early on, it became obvious that many candidates seriously underestimated requirements for obtaining a guide certification. High failure rates were common along with accusations of the ACMG being a closed shop and complaints of unrealistically high standards,” claims the history section on the ACMG website.

Citing pressures from aspiring guides, the association broke its certification into three streams, allowing for specialization in Ski, Rock and Alpine environments. Additional demands led to the apprenticeship program, also known as the assistant guide certification. It allows candidates for the rock, alpine and ski certifications to work in the industry prior to taking the full guiding exams. Indoor gym certifications, hiking guide certification and most recently an outdoor top rope instructor certification were developed as well, creating a hierarchy of instructing and guiding standards that currently span the country.

So What Does it Take?

There is an old saying “those who cannot do, teach.” The ACMG is an exception; you have to be able to do both.

“A paramount attitude to safety, immaculate technical skills, lateral thinking and problem solving, the ability to correct mistakes, professional appearance and client care that would earn a guide fabulous tips were they a waiter in a restaurant, … This could be a long list …” says Barry Blanchard, a UIAGM/IFMGA Mountain Guide. He has been involved in the guiding industry and its associated examinations since 1983. Blanchard remembers his own exam as being extremely stressful and arduous. “My [Summer Assistant Guide] exam was 21 days of mountaineering and rock climbing under the watchful eyes of Rudi Kranabitter and Pierre Lemire; there were multitudinous opportunities to fail.”

The long exam format offers candidates chances to redeem themselves and provides examiners with a sense of what each candidate is capable of. “At one point we climbed the north face of Athabasca one day, and the north ridge the next” says Blanchard. “Huge days, stressful days, but hey, mountain guiding is a stressful job, and at times incredibly so, so suck it up, buttercup.

School of Hard Rocks

Today, the ACMG Rock Guide exam, alone, requires you to be comfortable climbing 5.11 traditional and sport multi-pitch routes on any type of rock. This is high compared to our neighbours in the United States who require a 5.10+ standard and reflects the similarly high standards that exist in Europe. “Don’t let your climbing be the thing that makes you nervous on the exam.” Says Sarah Hueniken, an alpine guide who lives in the Canadian Rockies. “You should be climbing much stronger than they want you to climb so that you can focus on the guiding part and not on the ‘not falling’ part.”

Climbing a 5.9 traditional route might be a piece of cake for you, but imagine the same climb in a snowstorm with four inexperienced clients on your eighth straight day of work. Now it becomes a whole new adventure. It is here that having guides who are confident climbing many grades above what they are guiding begins to make sense.

If you are looking to be a full Mountain Guide, both the full Ski Guide and Alpine Guide certifications are required. “It is a lifestyle decision, the ACMG has much to do with the preparation,” says Blanchard, who is fully aware of the time commitment and sacrifices that guiding demands.

The full mountain certification requires movement up to 5.10 in rock shoes, 5.8 in mountain boots, alpine ice to 70 degrees, and waterfall ice to Grade 4. This necessitates training in multiple seasons and exams that are mobile, taking candidates to different terrain across the mountains. It is easy to see that in order to be a full Mountain Guide you need to put in the time; it’s a long process. “Mountain Guiding is experiential education. There is no short-cutting the fact that you need hundreds of days in each of the disciplines to pass the exams” says Blanchard. “It is not for everyone, indeed not for most” says Blanchard, making it clear that guiding is both a career and a lifestyle; not a part-time job.

Failure rates, especially on guiding exams used to be a problem. “[failures] used to be in a range of 50 to 60 per cent or higher” says executive director, Peter Tucker. “That is way down now, between ten and fifteen per cent.” The ACMG hasn’t lowered their requirements and maintains that examinations haven’t gotten easier. “I think people are better prepared” says Tucker. ” They are still tough, and they should be tough.”

ACMG WEBSITE: http://www.acmg.ca/03public/courses/mountainguide.asp

More than Just the Ropes

Being a guide goes far beyond knowing the ropes. The leadership and so-called ‘soft’ skills are just as important as the technical skills. Assistant Rock Guide, Will Stanhope acknowledges the importance of this, stating that he loves to guide “especially when the client is stoked, and he or she is making a breakthrough is some way.” That breakthrough is where the ACMG training plays an essential role. If you cannot reach your clients then you won’t be successful in helping them experience a new environment. The how-to of people management is a big part of what ACMG offers. “The ACMG made me as a guide” says Stanhope, who is a world-renowned professional climber from the west coast.

(Below: Walter Perren coaches 1950s Park Warden Ollie Hermanrude)

Teaching skills are particularly emphasized in the climbing gym instructor and top-rope courses. Beyond requirements for personal top roping and leading standards, candidates are expected to plan and teach lessons incorporating a number of different learning styles. They are also expected to demonstrate a profound understanding of risk management. Leo Van Ulden is one man who sees value in that. He is the owner of the Wallnuts Climbing Center in St. Johns, Newfoundland. He has taken the time to get certified in outdoor top rope and indoor climbing instruction. He notes, “Even if you know everything, it is still worthwhile to go get the certification to know that you know everything.” He has also offered financial aid to his instructors to go further west and get certified. He noticed the difference when they returned. “They came back understanding what their role was. They have more confidence and understand their liability.” There is a sense of integrity from a critical and thorough certification. For all guide and instructor exam courses there is an opportunity for retesting, but never in the professionalism or risk management categories.

Membership and Recognition

After enduring a training course and exam, successful candidates have the option of registering to become a member of the ACMG. Beyond the front window excitement of pro-deals and a market for your services, the ACMG offers group liability insurance, group accident/disability insurance and permits for a variety of public land agencies.

A board of directors manages seven to eight committees and holds meetings throughout the year to insure that members are operating within their certification levels, and to audit continuing professional development attendances to make sure that guides stay current. Leo Van Ulden sees the standards as an instrument in his own gym’s insurance. “My insurance [company] recognizes that we teach by the ACMG standard, and that does make a difference. It sets a baseline for liability. Knowing there is a national standard and knowing we teach by it makes us confident that we will be covered in court” he says. Van Ulden sends his staff to Toronto to get their certifications. “It is difficult for us, but it is so important” he says.

Eastbound

One of the hardest transitions for the ACMG has been the shift into eastern Canada. There are two factors that make this a challenge. First of all, there is a considerable stretch of flatland between the Rockies and eastern climbing, making it difficult for the organization to offer courses and certified instructors. The next factor is the difference in climbing terrain.

Van Ulden has been working on becoming a Level 3 Climbing Gym Instructor. He wants to get this so he can certify his staff without sending them to Toronto. Leo has also been trying to operate an outdoor climbing venture to inspire and guide more advanced clientele on some of the magnificent east coast granite. The limitations however, of being a Top Rope Climbing Instructor (single pitch, and top rope only) keep him from being able to instruct lead climbing outside. As a business owner he can’t justify spending the time and money to go west to get a rock guide certification even though he has years of experience on single pitch crags of his area.

The ACMG would like to offer “whatever courses the terrain is able to offer” says Tucker. Acknowledging limitations, having no glaciers to travel and no alpine available, the ACMG is still looking forward to expanding Assistant Rock Guide courses and Hiking Guide certification courses into eastern Canada as soon as possible. To date, there has been considerable success in the Climbing Gym Instructor courses into southern Ontario and effort has been made to start implementing the Top Rope Instructors course as well.

Very recently, Tucker was excited to tell me that discussions have been successful with the FQME (Fédération québécoise de la montagne et de l’escalade), creating a bond that will extend instructor training and program development.

A Canadian Standard

There have been many victories in the development of the ACMG. Recently, Tucker remarked that BC crown lands are once again accessible to guides. This is thanks to countless hours of lobbying and minister meetings. It is a big breakthrough made possible by the dedication of many volunteers. There is no question that the reputation and size of the ACMG greatly contributes to the success. Having a national standard could help to increase access in climbing locations across the country.

” The key purpose is protection of the public. If it can be simpler for the public to make that decision on who to chose as a guide, ultimately the risk management will be better” says Tucker.

The ACMG is constantly re-assessing their system and associated programs, to make them more accessible without compromising standards. The baseline requirements for any certifications are risk management skills, a willingness to share your passion and exemplification of a personal devotion to the lifestyle of climbing. It is an association that is constantly improving and re-inventing itself, working to meet the needs of Canadian climbers. “I think that the ACMG has a solid future with an increasing membership and presence in Canadian mountain culture. I hope that by the time I retire most Canadians will know what a mountain guide is,” says Barry Blanchard.

Lauren is a top-rope guide living in Toronto.