First All-Canadian Climb of El Capitan in 1969

"We were just a couple of twenty-year-olds from Squamish. We could do this, Couldn't we? The Nose was one of the biggest climbs of its type in the world in 1969 and at 31 pitches, two or three times longer than the longest climb we had done. It was big, psychologically and physically"

The following was written by Canadian climbing legend Neil Bennett for a 2011 issue of Gripped magazine.

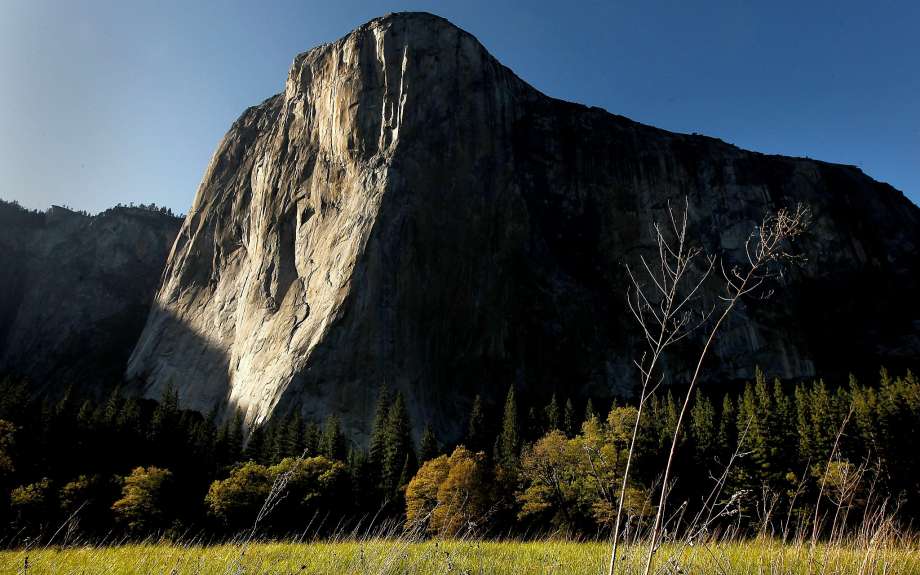

Morning in Yosemite Valley, the spring of 1969. Eggs by headlamp then off to the climb. I jump out of the car only to realize I am still in moccasins. Butterflies in my stomach. Back to camp, change footwear, and then back to the climb. To see the top of El Capitan, I have to hold on to the rock to avoid falling over backwards. Do the Nose? We’re just a couple of twenty-year-olds from Squamish. We can do this, can’t we? The Nose was one of the biggest climbs of its type in the world in 1969 and at 31 pitches, two or three times longer than the longest climb we had done. It was big, psychologically and physically.

Gordie Smaill and I had been climbing our guts out in Squamish during the summer of 1968 and it was his idea to head to Yosemite that fall. After a very long bus ride we were in the Valley and it looked like the sky had turned into clean granite. Unlike Squamish, there was no moss or lichen and no dirt and bushes in the cracks. During our couple of weeks we climbed the four pitches to Sickle Ledge on the Nose. That was how the Nose became one of the projects for the spring of ’69.

In those days we climbed and climbed and climbed – short stuff, long stuff, hard stuff, easy stuff, all training towards doing the Nose. We were fit and strong. We were also broke. For the Nose we had to borrow a haul line as we only had one rope but we couldn’t lead on the borrowed rope as it had taken a few falls. We wanted to take a bolt kit just in case, but we didn’t have one of those either. We borrowed a drill bit, but it didn’t have a holder, so we came up with a plan to hammer on the end of the drill bit only, just in case. Thank god we didn’t have to try it.

Gordie had read every publication he could find about Valley climbing and concluded that by the fall of ’68 the Nose had been climbed 17 times. We could be one of the first twenty parties to climb it. He also found that the fastest time was with two bivvies. We could do that. Canadian climber Jim Baldwin had assisted a couple of Americans in putting up El Cap’s Dihedral Wall with a couple of Americans – ours would be the first all-Canadian trip up the Captain.

Why was there so much aid? Well, gear was different – no cams or nuts – and shoes were pretty big and clunky. This was well before the advent of sticky rubber. And we climbed pretty heavy – we probably had 75 pins and 75 biners. Gordie called this “the usual shoulder bruising load” and it was all carried on 1″ wide slings. Aid climbing is inherently slow. You climb up your aiders, look at the crack and decide which pin will fit, take it off the gear loop, hammer it in, clip a biner, clip your other aider, move into that one, clip the climbing line, avoid rope drag at all costs and continue to the end of the lead. Build an anchor, tie off the climbing line so your partner can remove all the iron you just drove, then haul the bag, tidy up the gear sling so the handover to your partner is smooth and fast, maybe take a picture or two, drink a bit of water then belay your partner – on a hip belay – on the next pitch. Despite the inherent slowness of aiding, we had developed some techniques to make it as fast as we could and we intended to see if we could pull off a three day ascent of The Nose.

Back to El Cap. The four pitches to Sickle Ledge were familiar but after that it was all new, steep ground. You quickly realize how big the climb is as the top looks no closer from Sickle Ledge than it does from the ground. A few pitches higher, somewhere around the top of the Dolt Cracks, I started hearing voices. When you hear voices and you don’t think anyone is around, well, you begin to wonder if you have gone around the bend already. It was far too early in the climb for that.

Turns out there were four guys trying a new route off to the right somewhere. They gave up their climb and had to rap right over us on their descent. We were soon penduluming into the amazing Stoveleg Cracks, the only crack system in an otherwise unbroken expanse of steep granite – no need of a topo there. We freed some, we aided some, all in a crack system maybe 1000 feet off the ground. How sweet was that? The rock was so smooth there was nowhere for the haul bag to get fouled.

We bivvied on Dolt Tower, 11 pitches up and a thousand feet off the ground. Not as fast as we had wanted but OK. On to El Cap Tower early the next day and we found gallons of water from the party that had descended. This was important as we were trying to get by on one American gallon per day for the two of us and we filled our empty bottles. Above were Texas and Boot Flakes. Boot Flake expanded like crazy when we pounder iron behind it. I don’t recall if anything fell out below me but two things are certain: the pins were really easy for Gordie to remove and some day Boot Flake will be rubble at the bottom of El Cap.

The pendulum off Boot Flake is known as the King Swing. It is very exposed, tricky and 1,600 feet off the deck. Getting the haul bag across proved difficult. In lowering our haul bag off Boot we dislodged a rock from the only loose rock on the Nose – the grey bands. Moments later, to our horror, there was much yelling below us and we thought that we had killed someone.

“Do you want a rescue?” came up faintly from below. “Wave your arms if you want a rescue.” We stayed still.

We bivvied at Camp Four and we knew we had a long way to go to the top the next day. We were close to 1,800 feet off the ground and 20 pitches up – 11 to go. I don’t think we talked about it, we didn’t have to. We listened to the Hell’s Angels in the valley below and tried to sleep. We rose as the first light came into the valley, getting stiff hands to move, shoving down raisins and peanuts and, as always, taking care with the water.

Aid climbing is inherently hard on hands and knuckles. Nobody taped their hands in those days and rock crystals are sharp. After a while, the combination of dried blood, the black from handling aluminum carabiners, sweat, dirt and raisin goo make your hand into a kind of mitt: stick your hammer in and you’re good to go.

I was wishing I had brought my toothbrush.

The first pitch on our third day was the Great Roof and the view from the end of it is incredible, both up and down. The tiny little stance at the end of the pitch is some 2,000 feet off the ground and probably one of the most exposed belays on the climb. The 1,000 feet of the upper dihedral is an amazing place by any measure. There was pitch after pitch of glorious climbing – corners, straight-in cracks, free, aid, mostly great belays, and incredible photo ops.

A few times I felt someone tap me on the shoulder while I was on lead, far above Gordie. Or so it seemed. Turns out it was just the wind carrying up the haul line in a huge loop and that line was tapping me on the shoulder. It was a bit unnerving the first time it happened.

Somewhere around Camp Five a rock whistled by. We thought it was someone throwing rocks off, but curiously they were all about the same size. I watched one drop until it spread its wings and soared up. They were Chimney Swifts playing in the wind currents of the upper dihedral.

We were like climbing automatons – so fast, so smooth, so perfect. It was an incredible day in an airy, incredible place, a long way off the ground. It was the most amazing day of my climbing life up to that point.

We reached Camp Six by mid-afternoon, 26 pitches and half-a-mile up. “C’mon man, we can do this,” we said to each other.

By the time the sun was getting low, but we were close to the top so we knew we would finish that day. Gordie had the last lead over the summit bolt ladder and I think he did that mostly using Braille as he did not have the headlamp. This caused him to tie off to a little tree a yard or two from a really big bolt (after all, trees worked in Squamish). The base of the buttress, 3,000 feet below, was bathed in moonlight, and the big pine trees at the bottom looked like model railroad bushes as I cleaned the bolt ladder. Above was flat ground and sleep.

All day long, we had the rock that had fallen from the grey bands in our minds.

The next day we post-holed through spring snow and Manzanita to the Yosemite Falls Trail and headed down. Part way down, we sat where the spray from the falls drifted across us. A woman came up the trail and breezily enquired “Have you boys been camping?” We were draped in ropes and climbing gear, sweat runnels down dirty faces, hands showing much wear – yeah, we had been camping.

We snuck into Camp Four and casually enquired about an accident a couple of days before on The Nose, ready to make a dash for the park gates. Turns out the people who were below us were in the Stovelegs where the leader had fallen and broken a bone. It hadn’t been caused by our rock fall after all.

I had mixed feelings upon getting to the top. I was glad to have done the climb, and to have done it in three days. Yet it had been such an incredible climb I was sad to see it end. Who would not want to keep climbing at such a high calibre, in such an incredible place, on a climb with this much history and in such perfect weather? Afterwards, it was almost as though the air was let out of a balloon – I stayed in the Valley for a while to do more, but the weather changed and that was OK as my heart wasn’t in it any longer. I went home.

There were so few routes on El Cap in 1969 that after the party below us descended it was entirely likely that we were the only people on an El Cap wall route. Our record – having completed the climb at the highest standard of the day – lasted only as long as it took another team to best it, but, I think it is fair to say though that our ascent of the Nose opened the door to many more Canadians climbing hard in the Valley. It was a significant achievement for us personally and for Canadian climbing.