Hot Rock, Cold Water: Canadian Deep Water Soloing

While most climbers don't associate Canada with deep water soloing, there have been a number of areas developed for the sport over the years. Here is a story about Canadian deep water soloing from Gripped's 2009 summer issue

Many climbers believe that deep water soloing (DWS) is the latest trend, but climbing above water existed long before climbers knew what to call it. Its purest form happens every time kids go swimming, scramble up rocks and jump back into water. The most recent version encourages difficult climbing and the competitiveness found in conventional roped ascents.

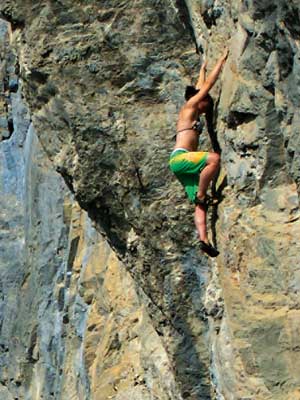

Jason Holowach shivered from a combination of excitement and hypothermia. His last attempt on a new route resulted in a 13 m fall into a glacier-fed lake. The frigid water instantly reduced the swelling in his forearms and temporarily shrunk his man-parts. With the possibility of another appendage-shriveling plunge, most climbers would abandon the route. But Jason, a simple beer-and-bacon boy from Saskatoon who has competed in many world cup climbing competitions, was unfazed by this sort of pressure. On his next attempt, he easily climbed to his high point, paused briefly and continued to the top, completing the route with a celebratory jump into the lake. The new climb, Heavy Flow 5.13 a/b was Alberta’s first serious Deep Water Solo.

Many climbers believe that deep water soloing is the latest trend, but climbing above water existed long before climbers knew what to call it. Its purest form happens every time kids go swimming, scramble up rocks and jump back into the water. Climbers have been doing the same anywhere the right conditions exist. Like kids, they view it as an opportunity to escape the heat and enjoy the thrill of ropeless climbing. The most recent version of DWS however, the version that encourages difficult climbing and the competitiveness found in conventional roped ascents, was introduced to North Americans only recently.

A 2004 film trailer tore through the online climbing community. The clip starred Klem Loskot attempting a route on an immaculate limestone wall – nothing new. The twist came when viewers realized he was unroped and climbing above the turbulent ocean off the coast of Spain. The perspective was nauseating and with the huge fall potential, the filmmakers must have been overjoyed to capture such an improbable scene. The clip’s climax involved Loskot coiling up and firing a massive dyno for a distant pocket. The action slowed, his hand came close and then he was off into the abyss, falling for what seemed like minutes before being swallowed by the violent foaming ocean. Seconds later he bobbed up for air, swam to a small ledge, rested and attempted the route again. Deep Water Soloing had suddenly been unleashed on the North American scene.

Normally associated with the sunny weather and warm oceans around the Mediterranean, the sport actually emerged from the dark and dreary UK climbing scene. As an island with an immense coastal cliff line, bolting restrictions and a group of dedicated climbers willing to climb on almost any rock and in any weather, the conditions were ideal for exploring difficult ropeless climbing above the ocean. It helped that the UK climbing media covered the activities, which eventually morphed into the influential DWS festivals. The sport would have likely remained on the island and viewed as just another British climbing oddity if not for the proximity of the European coastal cliffs and inexpensive flights.

The combination allowed British DWS proponents an opportunity to export the sport to more hospitable terrain. Suddenly the weather was warmer, the cliffs were taller and the water less frigid – the trifecta for deep water soloing. But these ideal conditions also highlighted the limitations of this new sport. Outside of certain countries like France and Spain, finding climbable rock is challenging and now that rock needed to be above deep water in regions with hot sunny weather. Other than the obvious Mediterranean locations, not many places could claim these conditions and for the sport to develop, new areas were required. Rather than look at existing sport climbing venues, DWS enthusiasts broadened their scope towards Southeast Asia.

Places like Thailand and Vietnam were originally promoted as the next great sport climbing destinations, but the complex travel logistics, humid weather and non-climbing temptations competed against climbing standards. Most climbers now see these areas as relaxing vacation spots, ideal for a little bit of climbing between lounging and beer drinking. These less-than-perfect climbing conditions however are ideal for DWS. In fact, the laidback pace of the region actually suits the relaxed nature of the sport, complementing the late starts, climbing attempts and evening festivities. Purists striving to increase the sport’s difficulties frown upon such distractions, but this emphasis on just seems to go with DWS. With pure difficulty and the need for perfect conditions and terrain removed from the equation, the viability of DWS locations suddenly broadens.

The pattern is not unlike what happened with traditional climbing, sport climbing and bouldering. All were originally associated with iconic sport-defining locations (Yosemite, Buoux and Fontainebleau) but only grew when climbers embraced their smaller, local areas. Limiting DWS to the flawless limestone shorelines of Spain, Thailand and Vietnam ensures its obscurity, but embracing local potential will help the sport grow. With this approach, Canada seems perfectly positioned to become a future DWS hotspot. For most climbers this is shocking statement, but Canada has all the necessary components for DWS climbing including an almost unlimited amount of coast/shoreline.

And while the country may lack Spain’s long sweeping limestone cliffs, much of Canada’s most accessible DWS is found on the Canadian Shield, with climbing on bulletproof ancient granite rising out of tranquil lakes and no risk of being swept away by rogue waves. The scene may not have the bikini-clad coconut-scented flavour of the more exotic DWS locations, but the rock is better and the climates warmer than what the Brits contend with. Perhaps our scene, like much of Canadian rock climbing is destined to be less sport-defining and more local in its appeal.

Where to DWS in Canada

The Rockies: A small group of local climbers is exploring the opportunities in Dacsawia near Canmore. This pristine spot has beautiful rock jutting up from a tranquil lake and is the most developed and documented DWS area in Alberta. This is also the location of Holowach’s Heavy Flow 5.13a/b and other more moderate routes like Foreplay 5.10. Numerous variations exist, including some futuristic looking lines, but climbers with less mutant-like abilities should explore some of the easier routes still awaiting an ascent.

Holowach points out that “all the routes were done in a true ground-up style with no top-rope rehearsal. We loved the sense of discovery and exploration every time we launched into a new line. Without a rope and gear, it felt like we were soloing, but without the negative consequences if we fell. I became so captivated with the area that during the summer I would go there and run endless laps on those routes as training. I’d climb until I was tired and then just jump off.” Although Holowach is a big DWS proponent, he not naive about the difficult Alberta conditions, “The biggest challenge with DWS in Alberta and BC is water temperature.”

It’s true that the glacier-fed Rockies lakes are cold, but during the short summer season, an occasional refreshing plunge can be refreshing. Holowach also believes “there’s potential for more DWS in the Rockies, you just need to get out there and look and be willing to deal with the cold water.”

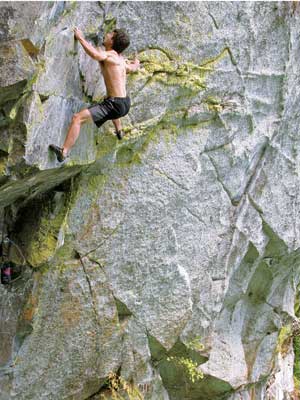

The West Coast: The BC scene is an interesting mix of boundary-pushing DWS enthusiasts and climbers simply enjoy some easy climbing above the water. Unfortunately, the lower angle of much of the glaciated rock eliminates many viable-looking DWS areas, but potential still exists. The most established areas are around Squamish and are a result of the vision and drive of one local climber: Matt Maddaloni.

As one of Canada’s most experienced deep water soloists, he’s been critical in developing the scene around Squamish including the Ocean’s Wall near the Squamish windsurfing spit, Lower Cheakamus River near the Paradise/ Squamish Valley bridge and the region’s most popular spot, Heaven along the middle of the Cheakamus River. For Maddaloni DWS represents the ultimate freedom for the climber.”You are unencumbered by rope and gear. You can push yourself to your limit with no fear of consequence. Your flow is not interrupted by placing gear, clipping bolts or worrying about a belayer.”

Maddaloni also acknowledges that “there may be routes in Revelstoke, Powell River and up along the coast, but climbers don’t take the sport seriously enough to record new routes.” As with much of the west coast, weather plays a huge role and cooler water temps and the long stretches of rain limiting activity. Finally, the long ocean-side traverse at Lighthouse Park in Vancouver is a classic example of climbers pursuing DWS even before it was formally recognized.

Canada’s East Coast: Canada’s eastern shoreline is guarded by immense unexplored cliffs rising out of the ocean. Local climbers have explored these areas for years and found exceptional bouldering and phenomenal ice climbing but the untapped potential for DWS is staggering. Much of the shore consists of immense menacing rocky outcrops pounded by the Atlantic but on calm sunny days the setting appears like something plucked from any number of articlecards promoting distant and exotic travel locations.

Access to these cliffs varies from easy park-and-play approaches to epic hikes requiring boat access but the biggest hurdle east coast climbers must overcome is the water. The Atlantic Ocean hovers at a bracing temperature during most of the year with only minor warmth increases during the summer months. As with much of the emerging DWS scene, ascents are not documented and the climbing lends itself to exploratory adventures rather than the paint-by-number climbing often encountered on well-documented crags.

Ontario and Quebec: The greatest DWS potential may lie in two of the most overlooked regions of the country: Ontario and Quebec. Both of these provinces have an abundance of warm water and extended hot summer temps – critical elements necessary for DWS. Combined with the almost limitless granite-lined lakes and limestone coastline, DWS opportunities in these provinces are almost endless. In Quebec the only established DWS area is near Le Lac Long west of Quebec City, but the prospects for DWS traverses and routes are incredible. Ontario is no different, with similar DWS possibilities in the Muskoka, Parry Sound and Northern Ontario regions as well as the limestone coastlines of the Niagara Escarpment.

Dave Voltan has recently become a DWS fan and raves about the Ontario scene. “During the summer, the temps are way too hot for climbing, but with DWS you can still get out on the rock. It combines the best of roped climbing and bouldering without the hassles of either and the water feels great on summer days.” As with much of the Canadian climbing scene, the DWS in Ontario and Quebec has its challenges and during the early summer, this can include maddening numbers of mosquitoes and black flies. And while the smell of DEET is no substitute for Pina Colada scented sunscreen lotions, there is something uniquely Canadian about it – like hockey, maple syrup and a Tim Horton’s double-double.

Climbers still not convinced about the DWS opportunities in Canada should remember that we have some of the most impressive pieces of untouched rock blasting through the currently frozen waters in the North; if global warming continues at its current rate this region could yield the world’s best DWS. But while we wait for these areas to thaw out, Canadian climbers should enjoy the more accessible local opportunities available in their home provinces.