Out of Nowhere – Nathan Kutcher

If you looked at the roster for the men's competition this past January, you probably wouldn't have picked first-time competitor Nathan Kutcher of St. Catharines to win top honors. "Nobody in the competition had ever even heard of this guy," competition director and Ouray Ice Park co-founder Bill Whitt said. "But he came and dominated."

Clipping the anchor of the 40-foot long dry tooling route, I leaned back and squinted up into the winter mist. From my stance, a long, arching roof peppered with fixed draws formed a dramatic finish to the top of the crag at St. Alban, Quebec. Having just completed my first dry-tooling route, I was ready to be lowered by my belayer, Nathan Kutcher, to my thermos of hot chocolate.

“Ok, go ahead and take!” I called, as snow began to fly. Instead of the expected welcome tug at my harness, nothing happened.

“You should keep going!” Nate’s voice floated back up to me a moment later. “You walked that thing!”

“That proves you weren’t watching,” I called back, glancing warily at the looming overhang. “Besides, there aren’t any holds!”

“Give it a shot!” Nate answered with a Cheshire-cat grin, paying out just enough slack to make the first clip out the roof.

Although it was our first day climbing together, I already knew it was pointless to argue. Clipping the draw, I torqued a pick in a shallow seam, gingerly placed a front point on a dime-edge, stood up and promptly skated into oblivion. A few more attempts brought similar results and back on the ground, I wondered aloud how such a route was even possible.

It was the winter of 2009, and I was one of many people who had no idea who Nathan Kutcher was. Our paths crossed over the years through various climbing forums and emails until an opportunity to sample the mixed climbing in Quebec gave us the chance to meet in person. While I was happy to bumble my way along and hopefully not impale myself on a tool, it was clear that Nate was a climber. Before the day was out, he had climbed most of the routes at the small cliff hiking nearly every line he got on. Strong as a bull with a quiet persona, Nate coached me through the basics of mixed climbing, citing the importance of things like steinpulls and not taking a tool to the face. Although he had been ice climbing just a year more than I, he was light years beyond me technique-wise and had a sense of balance on mixed ground that was astounding. Three years later, I wouldn’t be the only one astounded and many more people would know his name.

Each year, the Ouray Ice Festival in Ouray, Colorado hosts North America’s premier mixed climbing competition. Over the last 17 years, the best mixed climbers of North America and the biggest names in Europe have competed for bragging rights at the festival, which attracts over 3,000 people each year. Talents such as Will Gadd, Ines Papert and Josh Wharton have all claimed top honors at Ouray, and the festival continues to attract some of the best mixed climbers in the world.

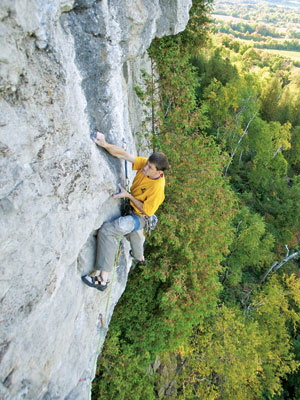

By contrast, southern Ontario is everything Ouray is not. The climbing scene is mostly relegated to widely-dispersed limestone and granite crags with more than a few access issues. Short, fickle winters and smaller cliffs (in comparison to the west) have most locals looking at mixed climbing as more of a way to pass the time until the next rock season than as a pursuit by itself.

If you looked at the roster for the men’s competition this past January, you probably wouldn’t have picked first-time competitor Nathan Kutcher of St. Catharines to win top honors. “Nobody in the competition had ever even heard of this guy,” competition director and Ouray Ice Park co-founder Bill Whitt said. “But he came and dominated.”

Kutcher became only one of two competitors to even finish the route and the first Eastern North American to ever win the overall competition. After dashing up the M10 line with 1:20 to spare, Kutcher collected his trophy and returned to Ontario, leaving a flabbergasted Colorado community to figure out what the hell just happened.

Those of us paying attention will remember seeing Kutcher’s name cross the headlines in 2011 prior to his performance at Ouray with the first ascents of the Centipede and Mandatory Overtime, Ontario’s two most difficult mixed routes. Checking in at a sandbagged grade of M10, these lines, along with dozens of other routes in the area, have established Kutcher as the driving force behind the progression of the small Ontario mixed scene.

So, how exactly does someone from an ice climbing backwater establish such cutting edge routes, not to mention pulling off what is likely the biggest upset in the history of the Ouray competition? A strong background in rock, a penchant for first ascents, and an ultra-driven personality are all factors, but perhaps the biggest role in Kutcher’s success is his sheer love of climbing and for the process of projecting hard lines. Kutcher discovered climbing in his teens and fell in love with sport immediately, tramping out to small, often chossy cliffs in his native Minnesota and neighboring Wisconsin, bumbling through his first top ropes and jumping into leading as soon as he could buy a rack. Without a mentor, Kutcher resorted to reading everything he could beg, borrow or steal on the subject. Taking the sharp end early on meant placing gear, and he cut his teeth on traditional routes out of necessity; unlike today, sport routes were limited and there weren’t many options under 5.10. If you wanted to climb, it usually meant top roping and trad climbing, not clipping bolts.

“It was all climbing to me. It seems today that it’s either sport or trad. It’s not just rock climbing anymore,” says Kutcher.

Little of Kutcher matches the mold of a typical top climber. He is unsponsored and works a full time job as an estimator at a lumber yard to support his climbing habit, a necessity which occupies a minimum of 50 hours each week. Prior to this, he worked as carpenter for nearly 10 years, capitalizing on opportunities for extended climbing trips, trading long shifts at the job site with long shifts at the wheel from Wisconsin to crags throughout the southwest. In 2006, he moved to Ontario after his wife, Rebecca, a native Canadian was seriously injured in a climbing accident. Full-time work and Ontario’s escarpment rock left a lot to be desired. Going to more established locations like the Gunks or the Red River Gorge meant 10 hours in the car, unpractical for the typical weekend trip. Kutcher, who was redpointing 5.12 gear routes, found the isolation of his new home beyond frustrating.

“Moving to Ontario felt like I’d been sentenced to prison,” he says with a laugh.

Prison or not, Kutcher was determined to find a way to keep developing as a climber. While the Ontario offerings were less than ideal, he found salvation in a few very motivating steep sections of cliff. He also learned to reevaluate his climbing goals, an approach which has paid off. Since moving to Ontario, Kutcher has flashed 5.13 and made a rare redpoint ascent of the 35-foot monster roof crack The Monument 12d at White Bluff.

Before ending up in Ontario, Kutcher and his wife had initially planned to move to Calgary. Forced to find a winter activity or hate life for half the year, Kutcher turned to ice climbing. An afternoon out top roping at a scrappy little cliff not far from his current home served as an introduction. Lacking any real ice gear, Kutcher borrowed tools and ended up climbing for the afternoon without crampons in a pair of old hunting boots.

“I think I was hooked the instant the tool first struck the ice,” he remembers. Kutcher immediately dumped over $2,000 on ice gear. Although a mid- winter thaw had melted any local climbing he gamely made the drive to the Adirondacks for whatever ice was left and immediately jumped on the sharp end after a quick lesson in ice screw placement.

While there were a lot of transferable skills from rock to ice, he also quickly realized there was a steep learning curve. The classic Scottish-style WI3+ Haggis and Cold Toast nearly ended his mixed career early. After negotiating the steep crux pillar, the novice Kutcher struck and loosened a surfboard-size slab of ice in the exit gully. Committed with his last gear out of sight, a terrified Kutcher gently stemmed on rock up and around the precarious slab, fearing the slightest touch would dislodge it. Sketching the remaining distance to the top, Kutcher took home a valuable lesson and a new interest in mixed terrain. “Over the first couple of years, getting on ice at the beginning of each season felt like I was basically starting over,” he remembers. “Now, I usually feel more confident dry tooling than I do rock climbing… at least until a tool pops.”

Back in Ontario, Kutcher didn’t have to look far for engaging mixed projects. Choss that was too precarious for summer rock climbing became more feasible with winter temps, and he began exploring new lines. Although the winter freeze made things more stable overall, it remained exciting. One route fell down completely just one season after it was established. Undeterred, Kutcher kept hunting for new routes and ways to develop his climbing, putting up Employee of the Month M9 in just his second season.

While he was developing mixed routes out of necessity, the joy of doing unclimbed aesthetic lines has always been his first love in climbing. He continues to spend much of his time establishing FAs of all grades, not just those that suit his current pursuits.

“I just like climbing cool lines. It doesn’t matter if they are easy as long as they follow a strong visual feature and have good movement.”

During his third winter mixed climbing, Kutcher would find a route that would not only inspire and focus his mixed climbing efforts for the next several years, but would also play an indirect role in his success at Ouray. While climbing at Diamond Lake he came across a line that would eventually become Metamorphosis M10 R. Featuring a steep headwall capped by a precarious hanging dagger, the route remained unclimbed despite attempts by other climbers. Kutcher knew that while he could bolt and likely climb it that season, but better style called for him to raise his skill to the route by establishing it ground up using as few bolts as possible.

To prepare himself, Kutcher continued to establish difficult sport mixed routes but also set out and climbed as many difficult ice and traditionally protected mixed routes as he could find. Although he worked on several long-term projects during this time, the gem at Diamond Lake remained at the forefront of his mind. Over the course of several seasons, Kutcher tried the route as conditions and his skills allowed, making slow progress up the cliff but big advances in his climbing.

While he continuing to climb mostly throughout Ontario, he also made short visits to other winter areas as opportunity allowed. Ice and mixed crags such as Pont Rouge and St. Alban in Quebec provided an ideal proving ground for climbing difficult routes and testing his drytooling skills. During one trip back to Minnesota, a friend and strong mixed climber James Loveridge introduced him to his training crag of Casket Quarry. Kutcher went on to onsight all the hardest routes over a couple of visits. Watching him onsight the second ascent of the area’s most difficult route, Extra Dry Vermouth M9, Loveridge suggested he consider applying to compete at Ouray. Although competitions in general had never interested him, after spurring by his wife he finally applied a few years later.

Unsure if he would even be accepted to compete at Ouray, Kutcher began training hard, rationalizing that even if he didn’t go, it would hopefully enable him to finally complete the Diamond Lake project. While not even considering the possibility of winning, being accepted to compete as an unknown from Ontario was a victory in itself. With the idea that Ouray was just another opportunity to push himself in a new environment, Kutcher arrived in Colorado that January excited to test himself and ready to enjoy the experience of climbing on a world stage. Surrounded by strong, experienced competitors like Will Mayo and Simon Duverney, no one was expecting an underdog to take home the prize, including Kutcher himself.

When he became the first competitor to complete the route, he was thrilled but did not expect to be in first place for long. “I climbed fifth, so I knew that there were plenty of people capable of finishing faster who hadn’t climbed yet.”

Not as thrilled was route setter Vince Anderson, who, after seeing an unknown waltz his route, was concerned he had made it too easy. “I didn’t know how good of a climber he was, and I worried, if this guy can do the climb, maybe everyone else will too.”

But, one by one, the contestants succumbed to slipped tools, pump factor or were simply outmatched by the severity of the climbing. Kutcher watched as climber after climber plunged into the abyss until there were no climbers left. When it was all over, he could hardly believe what was happening and was unsure if he had actually won.

“I have a lot of pride knowing I did it coming from Ontario and basically building everything from scratch. Ouray has opened my eyes to what I might be capable of.” Two weeks after his victory at Ouray, Kutcher finally sent Metamorphosis.

While returning to Ouray is on his mind, Kutcher isn’t preoccupied with it. He’s convinced that part of the reason for his success at the 2012 festival was the lack of expectation and pressure due to his anonymity, something which he won’t have the luxury of if he returns this January. While he plans to participate in the Ice Climbing World Cup events this coming winter, he is most excited about repeating a long list of difficult mixed testpieces in more established areas.

And as for his one-time prison of Ontario? “I have learned to like it, but I can’t wait to break out,” he laughs. “There is still more potential around here for some great lines, but I’m really excited to see what I can do in other, mixed areas around the world.”

Matt Desenberg is a rock and ice climber living in New England. Despite having climbed for 13 years, he still can’t drytool very well.