Get to Know the Diggers

While steep, hard climbs are naturally cleaner, moderate routes are covered in vegetation. To become rock climbs, they require the work of the Diggers, a leaderless, non-organized collective of otherwise ordinary climbers.

The original Diggers were 17th century English farmers who sought a more equal society. In 1968, the second coming of the Diggers in San Francisco created a free city in which food, drugs, and music cost nothing.

A third coming of the Diggers emerged recently in Squamish; these Diggers jumar fixed ropes with shovels and scrub brushes, seeking to unearth the next free climb.

While steep, hard climbs are naturally cleaner, moderate routes are covered in vegetation. To become rock climbs, they require the work of the Diggers, a leaderless, non-organized collective of otherwise ordinary climbers. While the previous incarnation of the Diggers were united with a cause and a handshake, the Squamish Diggers are a few dozen climbers who operate solo. We sat down with five Diggers to get their take on their inspiration, process, and philosophy.

Learning Curve

Squamish old-timers tell of climbing Diedre with only a rack of slings, for protecting the many trees. Most of these trees are no more, revealing a clean finger-locking corner. For moderate climbs to become clean, someone has to unearth them. Neither the government, nor the parks, nor the access societies do the work or support it financially. Moderate route development is by the people-individual climbers who independently pick a line, invest their time, effort, money, personal safety and comfort. They dig in the dirt, scrub in the rain, and then open the route for all to enjoy.

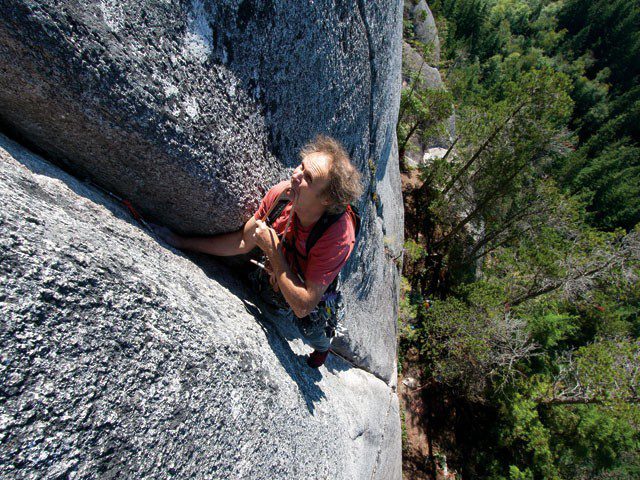

Don represents a new kind of Digger in Squamish. Being Vancouver-based and somewhat removed from the local Squamish community, Don approached digging without a mentor. “Route setting is really nebulous: nobody knows anything about it. You can’t go out and get one of those how-to books at MEC for $8.99.” This doesn’t thwart his compulsion to haul shovel and crowbar up the wall.

Just as new climbers gradually learn efficient ways on the rock, so do the Diggers on the dirt. Also Vancouver-based and newer to Digging, Damien’s infectious excitement makes him stand out in line at the Zephyr Café. With virtually no route development experience, Damien explored the wall that spawned Wiretap: “I hiked all the way around with ropes. I was so scared that I would get trapped on the wall and I had no idea about drilling bolts. So I went up with a double rack and pitons so that there would be no way that I couldn’t rap off this wall.”

While most Diggers set fixed ropes and leave them up for the duration of the cleaning process, Damien didn’t know that at first: “When I started, I didn’t even consider fixing my line. I just rapped. I had a belay device and a prussik. I would wrap the rope around my leg and tie a stopper knot.” Pausing, Damien realizes his mistake, “Cleaning is like climbing. If you take it on with no contact with anyone who’s done it before, you are so obviously at risk of learning it the hard way or making a serious mistake.”

The Diggers:

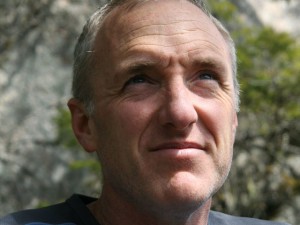

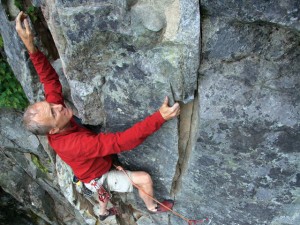

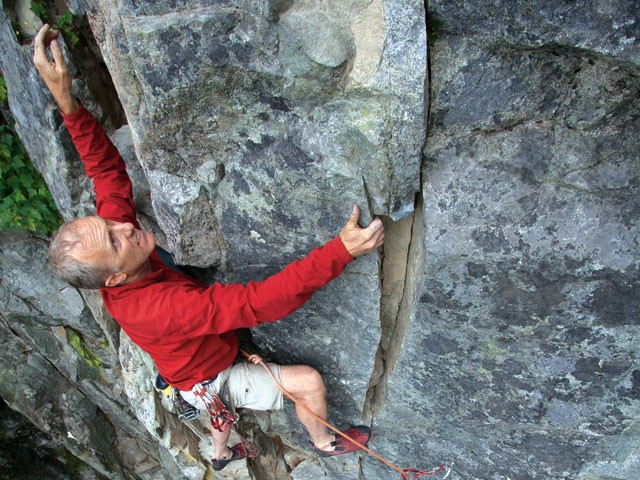

Dirty Harry Young

Occupation: Backhoe Operator

Age: 60s

Years Digging: 15

Routes: Tunnel Rock, Funarama (east side), The Great Drain, Bullethead East, The Feather, Squeamishness, Dean Channel, Chimp Dip, Cruising to Infinity, Black Zawn

Secret Weapon: Sleeman Pale Ale, Greasy Hamburgers

Damien McCombs

Occupation: teacher, guide. mechanical engineer in training

Age: 30s

Years Digging: 5

Routes: Wiretap Area, Everything Under the Sun

Secret Weapon: needle-nose pliers

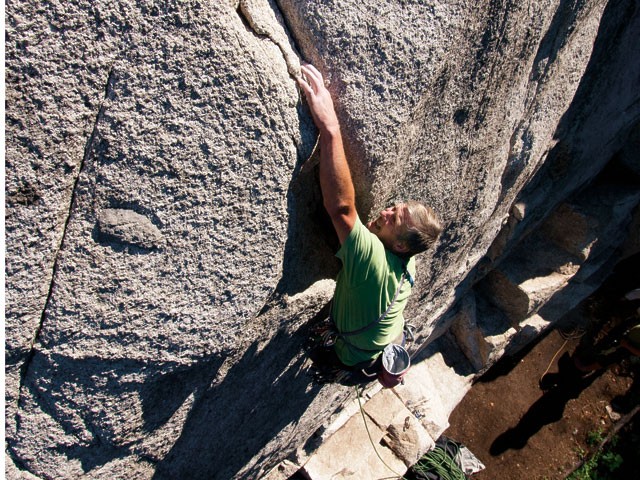

Don Cann

Occupation: Tech Ed/ Art teacher at a teen Psychiatric hospital

Age: 50s

Years Digging: 3

Routes: Area 44 (with Andre Lechner)

Secret Weapon: wire brush

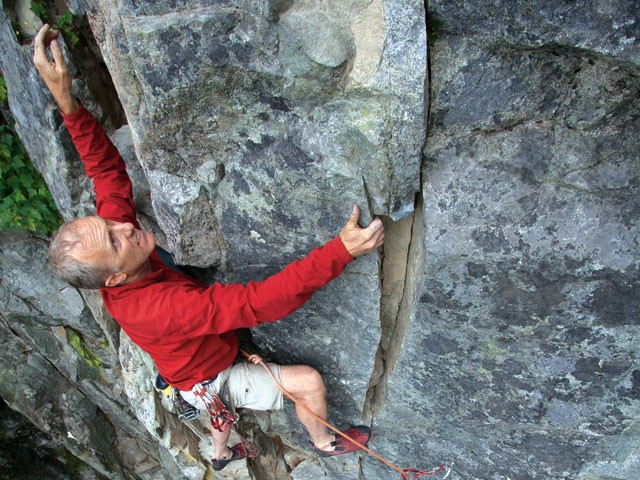

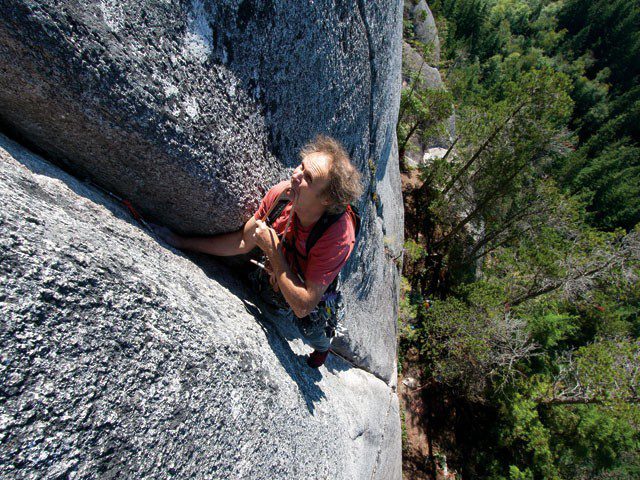

Kris Wild

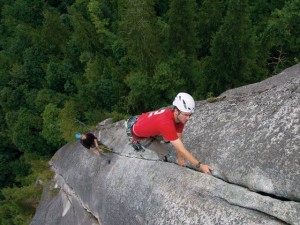

Occupation: Cabinet maker/rope access technician

Age: 30s

Years Digging: 18

Routes: Calculus Crack, Ultimate Everything, Polaris, Peasant’s Route, Millennium Falcon

Secret Weapon: ice axe, ibruprofen

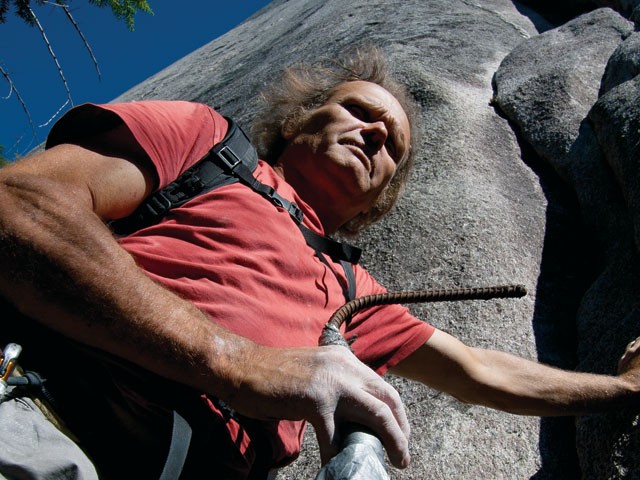

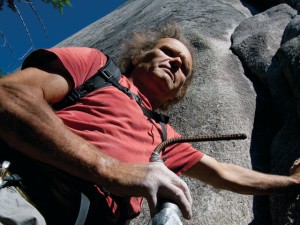

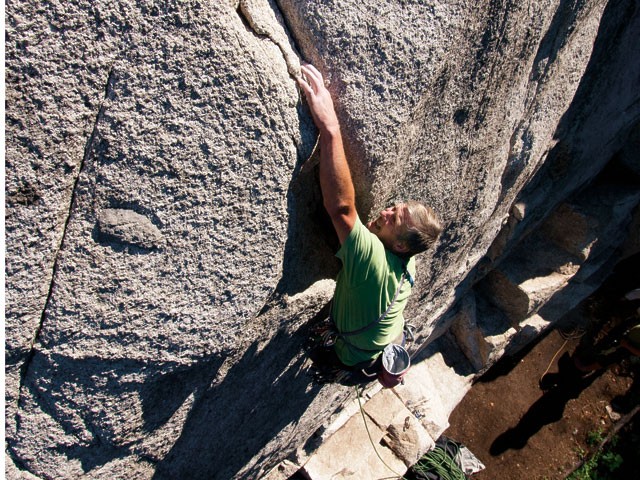

Hevy Duty (Alan Stevenson)

Occupation: business owner (HevyHuups)

Age: 60s

Years New Routing: 47

Years Real Digging (Squamish Style): 3

Routes: Funarama Centre, Lumberland

Secret Weapon: 20″ Estwing framing hammer

Incognito or Over Cappuccino?

Some Diggers are sufficiently concerned about criticism surrounding route development that they actively avoid the public’s eye. Area 51 is a top-secret compound where the US Military is thought to keep space aliens; similarly, Don and Andre’s climbing spot, called Area 44, was a secret project for two years. Don recalls being “very secretive initially because we didn’t want people coming in… So we’d wait until there were no cars on the highway before ducking into the forest. We wouldn’t put our helmets on.”

Dirty Harry is a kind-hearted Digger who speaks softly and carries a big pick. In some ways, Humble Harry might be a better nickname. Although Harry has scrubbed some amazing lines like The Great Drain and White Feather, he often deflects praise for his work to someone else’s vision or claims that he’s just “rescrubbed” someone else’s route. After years digging alongside Robin Barley, Harry seems worn out from controversy associated with route development.

Hevy Duty is an expat Brit in his early 60s; his roughened, lined hands tell of a life well lived. Unlike some of the other Diggers, Hevy is anything but shy. His short, bleached blond hair contrasts with the streaked blue pigtail on the side of his coif. His personality is as spirited as his haircut: in an English accent as thick as an old growth cedar, he’ll willingly tell anyone about his work.

It’s All Part of the Process

“Route cleaning is hard work,” said Hevy. “It’s just like doing concrete. There’s no easy way around it… Swinging a pick works you.” Digging is like a blue-collar job, only the work is more dangerous and money flows the opposite direction. Tools, hardware, and rope might run a Digger about $200 per pitch. They work on repetitive tasks leaving joints sore and knuckles bloody.

Each Digger develops a unique assortment of tools, such as scrub brushes, bent pieces of rebar for digging cracks, mattocks (like a big miner’s pick), crowbars, saws, ice axes, and shovels. Some Digging situations are too much for any of these standard weapons, and call for creativity and unconventional tools. Atop Lumberland (the crag), Hevy found a car-sized block perched on a slab. Even his 8-foot crowbar wouldn’t set it free. “If it’s not happening, you just go for a walk,” he recalls. Hevy soon returned with a car jack: “You just put the bar in, go like this ‘ching-ching-ching’ and the block went out.”

Cleaning means long hours working on the wall, hanging in a harness, with intense focus on manicuring the rock. “I was so uncomfortable I didn’t notice I was in pain,” recalls Don. “My balls are getting crushed, I’m hanging off a wall, and I’m super thirsty.”

Onsight

Kris comes across as an “ordinary” guy. Yet he is a master of detail and meticulous in his approach to route development. His research is thorough and his quality-control the highest. Just as different people have different standards of cleanliness for their homes, the Diggers have standards in the vertical world. While some leave roots poking out of cracks, others, like Kris, operate by a strict code, “I don’t want your fingers touching anything in the crack. I want pure skin on stone.”

Virtually every climb Kris develops becomes a five-star classic. Yet his structured work ethic is coupled with a free-flowing love of unconventional adventure. “Calculus Crack was a vertical line of shrubbery, which is exactly what it was like when Fred [Beckey] climbed it back in 1966,” recalls Kris. “They were just kicking toeholds into the heather. I climbed it a couple times like that just for fun. We’d go up there, tunnelling through the heather, grabbing handfuls of it. It was just hilarious.”

A big part of the process is research. Hoping and betting that a crack underlies a strip of greenery, the Digger takes a closer look. “I work my way down and poke my finger into the mat of moss and figure out if you could actually climb the features,” explains Damien. What seems consistent to the various Diggers is the hope of uncovering an interesting climbing feature from under a layer of vegetation. “You pull off a bit of stuff and it’s a surprise,” explains Damien. “It’s like Christmas. You just keep on opening presents all day.” What lies beneath the moss and vegetation is ultimately a mystery. To Hevy, “each route is a surprise. You’ve got to have an open mind and believe in the rock.”

Dark Side of the Broom

Digging isn’t all gleaming granite, first ascents, and fist bumps with climbing buddies. Most of the hours are in the company of only the pouring rain. The Digger becomes intimate with dirt and water. “The days can get pretty gross,” reflected Damien. “You’re rapping and there’s a line of brown slop coming out of your belay device right into your crotch.” Diggers endure these conditions all for a higher purpose.

One way or another, digging seems to be a means to an end of being part of and contributing to community. The end goal doesn’t always play out in a simple way. Spending many days working alone, Damien recalls “coming down from working alone all day for 10 hours and just being black with dirt and chafed and mosquito-bitten. Walking through the campground and all these people are having so much fun. It was hard because they had no idea what I had been doing… People would be talking about all the climbs they did that day and I couldn’t really interact. I felt like an outsider.”

At other times, Digging leads to not just distance but also outright conflict. Harry described a time when his friend, a well-known Digger (who will remain anonymous), questioned his choice to work on Tunnel Rock, asking, “What are you cleaning this piece of shit for?” While all Diggers have relatively thick skin (both literally and figuratively), criticism seems to breach it.

Good Old Days

Is Squamish nearly all dug out? According to Hevy, not even close. “There’s so much potential on the Chief. There’s more unclimbed rock I can see than in the whole of the UK.” To Hevy, these are the good old days. “This place will rise and it will be cool, it’ll be a climbers’ town. Everywhere has its time. And Squamish’s time has not come yet. It’s coming and it’s a magic spot. And I’m lucky to be in its second Golden Age.”

A Digging Manifesto

Why does the Digger dig? Perhaps Diggers get something from the process, like respite from other worries. “You get pissed off with life and you swing the mattock that much harder,” confesses Hevy. Digging can also keep the idle mind busy, giving the Digger a goal worthy of effort; the process becomes the reward. In the words of Harry, “When you start something, you have to finish it. To finish it becomes the ultimate goal.” The motivation to dig may reduce to simpler pay-offs yet, like the rewards that come when crossing paths with thankful climbers at the pub. To Harry (and perhaps others), this anticipated pay-off is all about the “beautiful women… and lots of beer.”

Then again, The Diggers’ investment of effort and money seems to far outweigh the pay off (in terms of recognition, women, and beer) they may receive. While none of the 2011 Squamish Diggers would likely think of themselves as counterculturalists (unlike like the previous incarnations), the same utopian vision may be part of their motivation. Damien, for example, originally decided that he should put up one pitch every year. “Considering how much I get out of Squamish, it just seemed like a way to give back. That’s kinda funny because I didn’t even know whom I was giving back to.”

Don wonders if an extraordinary vision underlies Digging: “We have a money economy. You want something done, you’ve got to give me some of your resources and I give you something in exchange. But there are a lot of different economies out there that get ignored. Climbers, at their own expense, go out and make a climb, pay for it themselves, and it’s always free. We are involved in something pretty special beyond just climbing. It’s this thing that’s free. Where else does that happen? What else is free?”