Two to Peru

Their plan was simple. Drive south through Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica and Panama to the end of the road at Panama City, hitting every bar and beach along the way. Leave the car in Panama, fly to Bogota in COlombia, travel by bus through Colombia and Ecuador into Peru, and try to climb at least one 6,000 m peak.

“My government and the Ministry of Tourism welcome you to Peru. Your flight was good? You arrived today?”

“Thank you, Senor. Yes, we arrived in Lima this morning, but we didn’t fly. We came all the way by land.”

“I think that you are the first ones from Canada to climb in our country. There are how many in your party?”

“Right now we have two, but there is a good chance that we’ll get a third. We left most of our gear in Panama, so we’re hoping that we can borrow a few things like ice-axes and crampons from some local climbers.”

“You come by land from Canada, and you have no equipment? And you are only two, or maybe three? You have a big country, with many mountains, so I would think of more climbers. Which mountains do you wish to climb?”

“We were hoping you could help us decide that.”

It was April 1965, and Hamish Mutch was talking to Caesar Morales Arnao, the Ministry of Tourism official responsible for assisting foreign climbing expeditions to Peru, who was also president of the Andean Club of Peru. Morales was not impressed.

Two University of British Columbia students, Gordie Dunham and Hamish Mutch had decided to take a year out of school, and spend part of that time travelling overland to Peru and doing some climbing in the Andes. Although they both lived in Vancouver, this trip really started and ended in Yosemite, where Hamish had planned to spend most of the fall of 1964 climbing with his close friend Jim Baldwin. Unfortunately, Baldwin had died in a rappelling accident earlier that summer, so Hamish travelled to Yosemite by himself. Here he was lucky to pair up with another young climber named Jim Bridwell, who was also living in Camp Four for an extended time.

The weeks became months, and while routes were being climbed, the sunshine turned to rain, and the rain turned to snow. Gordie, who was working in a pulp mill on Vancouver Island, had promised to show up sometime after Christmas, when he had saved enough money. The snow gradually got deeper, until by early January even Bridwell had seen enough, and he left for the comforts of San Jose, leaving Hamish as the only climber in Camp Four, and indeed in the whole valley. Most of his time was now spent in the lodge, drinking coffee and trying to stay warm and dry. He also studied Teach Yourself Spanish and de la Vega’s classic The Incas, as preparation for the long journey south. In the middle of the month, Gordie drove up in his worn old Pontiac, and the trip officially began.

* *

Their plan was simple. Drive south through Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica and Panama to the end of the road at Panama City, hitting every bar and beach along the way. Leave the car in Panama, fly to Bogota in Colombia, travel by bus through Colombia and Ecuador into Peru, and try to climb at least one 6,000m peak. Then repeat the whole trip, backwards this time, picking up the car again in Panama, and visiting any bars and beaches missed on the way south. By and large, this plan worked very well, although the pair admit to missing one or two of the beaches.

(Tom Wells drifts from Equador to Peru)

The first stop was a quick side-trip to San Jose to pick up Bridwell, who had insisted that the three of them spend a couple of days at Pinnacles National Monument, to climb some farewell routes. Later, he looked a little wistful as he watched his two friends head south for months of sun, sand and cervezas. His own first trip to South America would not take place until fourteen years later, for his iconic ascent of Cerro Torre.

After checking the sights of Mexico City, it was time to try an ascent of Popocateptl 5452m, to see how they fared at altitude. They spent the night in a small hut at 4725m, and cramponned easily to the chilly summit the next morning. They then drove to Acapulco for a week on the beach, before climbing Iztaccihuatl 5286m. With misplaced confidence they decided to attempt this as a day trip from the car. Since considerable energy would be required, they each ate half a chocolate cake and drank a large Coke before starting out. On reaching the ridge at 4725m the effects of chocolate cake and a week at sea level caught up, with predictable results.

(A youthful Jim Bridwell at Pinnacles, New Mexico)

The pair had originally planned to pitch a small tent every night, and cook their own meals. After a couple of days they switched to sleeping in the car, and eating the ‘comida del dia’ specials at the local restaurants. Since sleeping on the front seat was more comfortable than the back, they changed places every night. At Tapachula on the Mexico/Guatemala border, visa problems dragged on for a week. There was no rush, so they spent the days swimming at nearby Puerto Morales, and the nights in the car, with the windows open. Unfortunately, Tapachula was a major malaria centre, and a visit to a doctor later confirmed that Hamish was suffering from ‘el paludismo’. Quinine was readily available, and large doses solved the problem.

Two months after leaving Yosemite they reached the end of the road at Panama City. The Darien Gap which links Central America to South America is a massive swamp, which is impassable to vehicles. After storing the car, they flew to Bogota, Colombia and caught a bus. They had decided to leave all of their climbing equipment except warm clothes, sleeping bags and boots, hoping to borrow the rest from climbers in Lima, if they could find any.

The roads in South America varied between bad and very bad, and the busses were worse. Progress was steady but uncomfortable until they reached the Rio Zarumilla, which forms the Ecuador/Peru border. Relations between the two countries were strained, and neither would consent to building a bridge for fear of being invaded by the other. Here they met American Tom Wells, who was driving a Land Rover and also looking for a way to cross the river. He offered them a welcome and more comfortable ride. Two days later, without finding a bridge, they reached a small riverside village where the main activity was floating bananas across the river into Peru, on balsa wood rafts. Another two days went by while the villagers built a larger raft, which they claimed was capable of floating the Land Rover across. Somewhat doubtful about this, and feeling rather guilty, Gordie and Hamish took their packs out of the car, and watched nervously from the bank as Wells and his vehicle wobbled across the river, on a raft barely bigger than the car. When the raft had landed safely in Peru, some distance downstream, the two friends rode across in a dug-out canoe.

Further south, they took the train up the Rio Santa valley to check out the weather and snow level in the Cordillera Blanca. They spent a memorable week in Yungay, hiking by day while learning to play Casino and drinking beer with the locals at night. Conditions looked reasonable, so on to Lima to get organized. Arriving there in the back of a potato truck, they asked for directions to ‘the cheapest hotel in town.’ They were sent to the Hotel Hawaii, where they were astonished to meet their friend John Ricker, also from Vancouver. John had been working in Antarctica over the southern summer, had ridden to Buenos Aires on an ice-breaker, caught the train across the continent to Lima, asked for ‘the cheapest hotel in town’, and arrived at the Hawaii thirty minutes before the other two. What were the chances of that? John quickly agreed to join the trip.

Following several meetings with Morales, and making a hand-drawn copy of the local map, the trio decided to climb in the upper Ishinca valley. Some essential purchases were made in Lima, two plastic sheets in place of a tent, a kerosene burning stove and forty-five feet of skinny hemp rope. Gordie and Hamish left first and John would follow a few days later. They took John’s nylon rope, ice-axe and crampons. After borrowing another axe and crampons they now had enough essential equipment for two people. A couple of days were spent in Huaraz, scouring the market and stores in a vain attempt to find some tasty lightweight food. Finally they settled on an unappetizing menu of oatmeal, canned pilchards, powdered soup, bread rolls and Jello. They would eat these five items in various harsh combinations and permutations for the next two weeks. Based on prior experience, they ruled out any chocolate cake. After adding a large can of kerosene, they were now ready for the high peaks.

The two friends took turns sitting on the ground, putting on their overloaded Trapper Nelson packs, and pulling each other upright again. Their hand-copied map indicated a small settlement called Collon several kilometres up the narrow track. They hoped that this would be a good place for hiring a burro, to carry their loads further into the mountains. Unfortunately Collon was only a farm, where all the men were engaged in the spring ploughing, using teams of oxen, and no burros were to be seen. Somewhat discouraged by this, they continued slowly up the path. Small bundles of firewood lying beside the trail told them when one or more of the local women was hiding cautiously in the brush. The first night was spent in an empty grass-roofed hut, where they happily traded a can of pilchards for a night’s rest and copious disappointing hits of coca paste while the overhanging side of a large boulder served as camp two. On the third day, they reached the end of the Ishinca valley and turned south up the steeper Yanaraju branch to finally arrive at an old stone hut, which had been built for alluvion control. At this height, the daily rain showers had changed to heavy snow, and their plastic sheets were used to fix the roof.

(Gordie and John on the summit)

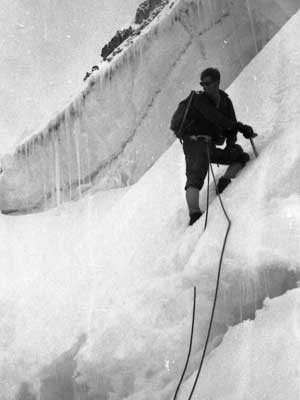

The next few days were spent hiking near the hut to acclimatize, getting mildly snow-blind, recovering, and making a relaxed ascent of Nevada Ishinca 5,535m. By now, John had arrived, and the three made a recce towards Nevada Ochkapalca, an unclimbed peak nearby. After a rest day they decided to make an attempt on Nevada Ranrapalca 6,166m. Since they were now three people, with only two axes and two sets of crampons, some compromise had to be reached. John would lead, using his own axe and crampons. Hamish would come second, with an axe to belay John, but no crampons, while Gordie would be third, with crampons, but no axe. Gordie had found two large sticks in the hut, and he substituted these for an axe. Fortunately, the effectiveness of this system was never put to the test.

They had no idea where the regular route went, but had spotted a likely line from Ishinca. Leaving at 6 a.m. they kicked steps up to about 19,000′ on the north east face, before retreating at noon, due to softening snow. After another rest day, they left the hut at 3 a.m. and made good progress in their frozen tracks, to their previous high point. Here the slope got steeper and icier, while their progress slowed accordingly. The weather was deteriorating fast, as they crossed the summit plateau on a breakable crust, to reach the peak a little after 12. By now, there was nothing to see except clouds and fog. Since they had forgotten to bring a Canadian flag, they had to make do with an orange tea towel purchased in Mexico. Their descent was described in Hamish’s diary:

“We start down and reach the summit ridge at 1.15, weather socked in. Gets slowly worse as we move down the ice pitches. Steps covered in new snow/hail which pours down the face like sand. Reach the bottom of this at 4.30. Powder snow all piled up, dangerous avalanche conditions. Continue down to couloir using both ropes for more speed. [the second rope was made of thin hemp]. Lower we can’t see f.a. Expect an avalanche any minute. Finally find the spot to cross the schrund–a complete whiteout. Head in the general direction, and fortunately spot our old tracks. Several inches of new snow. Leave the glacier at 6.00”

With lots of food and fuel left, they spent the next day relaxing and discussing their next move. They had two options. Either set up a high camp and attempt the unclimbed Nevada Ochkapalca, or move across the valley and attempt Nevada Toclaraju. This decision was made for them the following morning, when the pump for the stove fell into the fuel tank. On day 13 they headed down to Huaraz.

Later, back in Lima, the three said their farewells. John was staying on in Peru, to do some more climbing when the real climbing season arrived, in a couple more months. They agreed to get together in Vancouver that fall for a few beers and a slide-show. By riding the busses for up to 22 hours a day, the other two made good time back through Ecuador and Colombia. They picked up the old Pontiac in Panama, and continued northwards. It was snowing lightly as they drove over Tioga Pass and into Yosemite, during the third week of June. In Camp Four they were warmly greeted by their old friends Bridwell and the Bircheff brothers, and happily accepted an invitation to share their site. After supper they all headed to the Meadows, to check on the progress made that day by Yvon Chouinard and TM Herbert, who were about one third of the way up El Capitan, on their first ascent of the Muir Wall. They had been away for 153 days, and it was good to be back.

–For various reasons, such as the fact that the trip occurred at least two months before the normal season started, did not use the customary high camp, and was by far the earliest date that a 6,000m peak had been climbed, this ascent was not recognized by the Peruvian authorities for several years.

–John stayed on in Peru for many years, working as a consulting geologist and amassing an impressive list of ascents. He later wrote Yurak Janca, the first guidebook to the Cordillera Blanca, and a true classic in Canadian mountaineering literature.

–The planned meeting in Vancouver did not occur for 27 years. There was no slide-show.

–Later that summer, five members of an American party tumbled down the same face on Ranrapalca. Two of them died from the fall.

–Gordie tried to take one of his sticks back home as a souvenir, but left it on a bus in northern Peru by mistake. He earned the nickname of ‘Stickman’.

–In 1970 a massive earthquake and subsequent alluvion engulfed Yungay, at an estimated speed of 300 km per hour, killing all 17,000 inhabitants. Another 60,000 people living in the Rio Santa valley also perished.