Facts Over Fiction: C4HP Brings A New Age of Training

A conversation with Dr. Tyler Nelson on Camp4 Human Performance, training theory, full-crimp hangboarding and finger-curl concentrics

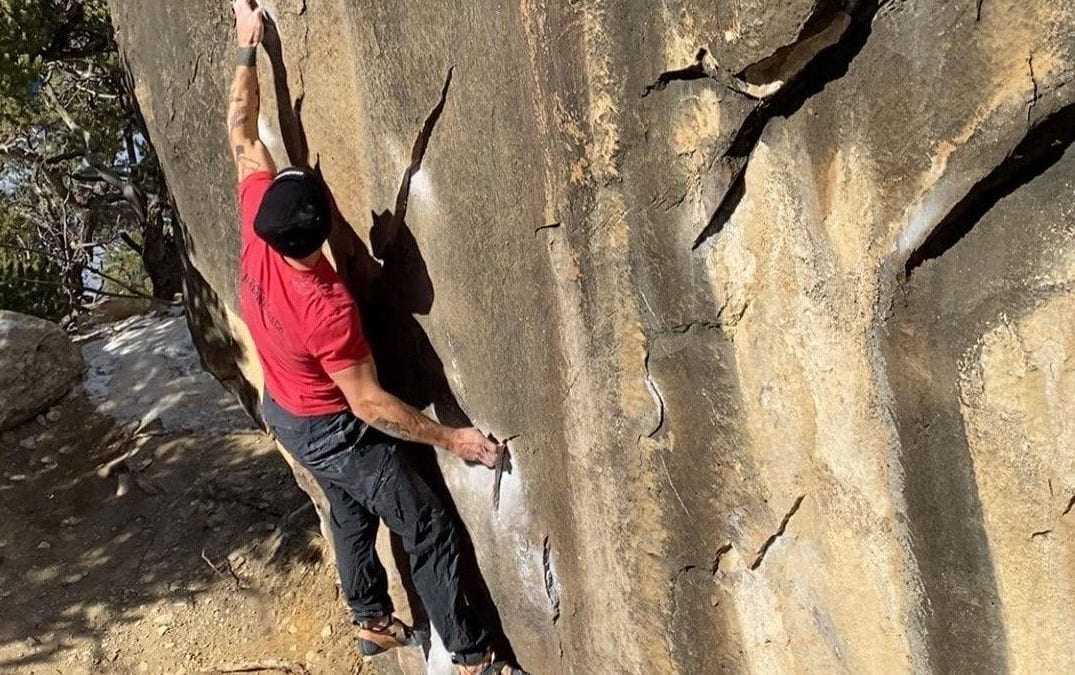

Photo by: Dr. Tyler Nelson

Photo by: Dr. Tyler Nelson

Dr. Tyler Nelson has become a household name among board-baring boulderers. His scientifically-backed, individualized approach has earned him clients such as US National Champion Alex Johnson, while his research-based training methods continue to satisfy a info-hungry training audience. For those obsessed with training, his business, Camp4 Human Performance, has become popular on Instagram for exhibiting new exercises that target tendon strengthening and conditioning.

In the past, climbing-related research was rare, and tendon-specific material even less common. Why, then, did Nelson approach this relatively unexplored subject?

According to Nelson, “It wasn’t always my goal. I went to school and got a Bachelor’s Degree in cultural anthropology. I am interested in social science and that is what got me excited to study and learn. I have always loved science, but social science in particular. I drew toward the subject until I was in graduate school. At that point in my life I was working at a law firm and had ideas that I was going to go to law school. I was going to do social work and become a teacher.”

At that time, Nelson’s father worked at a university in Missouri. The position allowed for Nelson to attend graduate school at no cost, and naturally brought the recent undergrad through his postgraduate education. Seeking an opportunity to change his focus to the sciences, Nelson would become a physician with a focus on education.

“The best thing doctors do is give people options for their health care problems. There’s lots of education, lots of communication, and lots of relationship building. I have always loved sports and have been an athlete my whole life. It seemed like a good fit for me. Now it has been six years that I have been out of graduate school. I am now less less interested in the physical applications than I am in the education.”

“In grad school, I was able to complete a Master’s Degree at the same time as a Doctorate. I did my master’s in tendon rehabilitation. It was my main interest. I was in love with climbing by then. I had been going to Camp 4 in the summer with my friends: dirt-bag, sleep-in-the-woods kind of thing.”

“When I came back, I was interested in exercise science and realized that there were not a lot of exercise-science applications for rock climbing. I started seeing what people were doing, and hooked up with Steve Bechtel. He and I became close colleagues and then started a conference that we teach. It spurred from there.”

“There was a clinic in Missouri that I liked the set up for. It was called Central Institute for Human Performance. It was a chiropractor, a physical therapist, a strength and conditioning coach, and a massage therapist. It was a lot of different practitioners under the same roof. It was essentially this idea that there is no simple fix for a problem. Each of those practitioners has a specific skill set, and one is not better than the other. They are unique. Having a multi-factorial approach to a problem is the best way to manage health care. Coming into starting a business, I had that in mind. I wanted to have that same model for my business.”

With his focus on tendon health, Nelson would become naturally attracted to fingerboarding. Though seemingly a boulderer himself, Nelson began climbing with a love for traditional-adventure climbing. With 17 years of experience, Nelson has explored the climbing’s many disciplines and, in congruence business, has adopted bouldering as a focus for his strength training as well as his personal climbing.

As anyone that seeks progression in bouldering already knows, finger strength is essential.

“I think, in general, fingerboarding makes sense to people. A way that we can put more load on the fingers than we do when climbing is by hanging on the fingers. That has been intuitive for people to understand, but now, when something comes out of a research journal, people make the assumption that because that is a researched method, it’s the way to do it. The reality is there is nothing particularly special about a 10-second hang.”

Eva Lopez’s 10-second hang, “was specific to her as an individual. Eva would absolutely agree with this because I have talked with her quite a bit. Where Eva Lopez used 10 seconds because that was her average time, you might use 5 seconds, I might use 6 seconds, and someone else might use 7 seconds. We can be general and say, ‘Sure, hang on for 10 seconds and your fingers will be stronger’, but that is only one way to train the fingers when there are lots of different ways.”

“One thing that I think people are interested in is, ‘What are all of the options, and which one is best for me?’ That is where people tend to be out in the woods and confused as to exactly what they need to do to make their fingers stronger. When should we modify the program? That is where my detailed understanding of connective tissue can be helpful.”

“When it comes to the time frames at which we apply some sort of finger-training program, there can be lots of assumptions. In the periodization model, the sport science community, in general, is not very good at predicting when people are going to be at their peak performance.”

“I usually play on getting people to think about how much finger force they really need for climbing. I know too many climbers that will do a 10-second weighted hang and that is their strength-training protocol. They will do it for years and years and years.”

“There is this concept of hormesis that is: anything at too much of a dosage is risky, not helpful, and can be toxic. The easy example is drinking water. You can drink too much water and you are going to drown, but water is important for our bodies. The same thing applies for a 10-second weighted-hang, or any sort of finger-training protocol. At some point it needs to change.”

From a connective tissue stand-point this has to do with tendon stiffness. The stiffer the tendon, the faster the force can transfer across a person’s joints. The easier power can be transferred then the more powerful the climber becomes. Nelson said, “This is good for climbing because when we are at our limit we need to be powerful, but it is risky for the health of our connective tissues. If I make my tissues more stiff, I potentially pull my tendon away from my bone, or the pulley away from the bone or I get a muscle pulling away from the tendon.”

“There is certainly a limit to how much stiffness an athlete can put on their system before they have an injury. When we reach that level of strength and stiffness, we are performing at the highest level. This is usually when we should back off. That is a hard thing to understand and a hard thing to apply to yourself. I have a hard time applying it to myself.”

“Climbing is fun. When you are performing at a new level, you want to climb more. We can do that for maybe two weeks. The block models would suggest 10 days is a peaking duration where, at some point, we need to stop all of the velocity stuff. That’s when we want to go back to strength training.”

“After strength training for a period of time, we should be able to introduce stiffness again. Strength training is all about reducing stiffness by doing things that are slow and heavy.”

“If we load heavy,” as with hangboarding, “then we load slowly automatically. And if we extend the time-under-tension, we recruit more muscle mass. As we recruit more muscle mass, we use a greater percentage of the tendon. Strength training is all about increasing the amount, in terms of percent maximum, of the tendon that we are actually using for a given effort.”

“If I load really quickly, and I train my system to recruit muscles really quickly, I am not using all of my tendon because I load too quickly. As I do that more and more, what I do is I train my tendon to be really stiff so when I pull only 60% of my muscle, I am still loading a high percentage of my tendon, but it is not the same load as if I am loading very slowly.”

“The rate, which is the speed and the magnitude of the loads that we put on connective tissue, defines how that tissue responds to whatever it is that we are doing. If I load slowly and heavily for a long period of time, the water molecules actually have time to separate so I can load the majority of my tendon, but if I load very quickly, the water molecules act very stiff and the tendon acts like a complete unit.”

With all of that said, how do we approach training our fingers? This is where many climbers have difficulty separating facts from fiction. A nice guideline to follow is to train that which you need to climb harder. We often hear that hang boarding the full-crimp hand position is dangerous, but what if you climb with the full crimp? Is it really best to not train it befpre hand?

“Usually when people say that, I answer it with a question. ‘Can you tell me why it is a bad idea?’ My argument would be that it is more risky to not train it on a fingerboard.”

“I will do density hangs until failure. I went from 10 seconds to 15, to 20, to 25 seconds on a 15-millimetre at full-crimp. Certainly, a lot of volume of anything will make your fingers sore, but if it is a controlled environment like it is on a fingerboard, and I am loading slowly, moderately-heavy to failure, there is no real risk in doing that. What this has done over time is that it has increased my ability. Now I can hyperextend my joint, and I can do so at a position where I can better get my fingers on a hold at a full-crimp.

“The only way that I am going to get better compliance and an increased range of motion at that joint is if I strength-train my fingers to load them heavy and slowly. A way is to do this is long duration full-crimping hangs on a fingerboard.”

Full-crimp is not the only variation that exists in relation to conventional finger-strength training. Nelson said, “There are lots of ways to train joints and types of muscles for types of strengths. The finger-curl position is really about hitting holds. I’ll hit things open handed a lot, and try and pull into position, but I am not very good at that as a skill. I have a friend that can just pull his fingers in every time he hits a crimp. I just cannot do that.”

“That is a big advantage for him because he can get on top of small holds. Trying to find a way where I can increase my ability to flex my fingers makes sense. Climbers can get stuck into a way of doing things. People will hang on their fingers and use specific finger positions, but that doesn’t necessarily train getting into that position as well as it could if we were doing something like a finger curl.”

“That stimulus that we train that is unique is going to give us some sort of adaptation. I have done a decent amount of hanging on my fingers, as have most climbers. This is just another stressor that is going to give us that little bit of advantage when we are training.”

While finger training is important, Nelson said, “Go outside and go climbing. We certainly can get way too distracted with finger training. Climbers tend toward being anxious about climbing and exercising. We all do too much anyways. If you get the chance to go outside and climb on a day, skip a training day. It doesn’t matter, don’t even feel bad about it.”

“The natural predisposition of an athlete with our personalities is to do more. That is what I would always do when I was younger. I now know that was totally unhelpful. I have had way more success doing ‘rehabilitation’ with clients, even remotely, by dropping things out of their program. We are generally already pushing it too much. We want to take away enough so that they are recovering and actually getting an adaptation from that recovery, not just getting tired.”

While the above only touches upon a couple of the aspects of Dr. Nelson’s research, it does show the multiple instances where any athlete could get more from their training simply by taking an anatomical approach. This is difficult to do by oneself as it requires the knowledge and understanding of person that has done the research and read through the papers that relate directly to the cruxes of our exercise. That is why Camp4 Human Performance exists.

Today, Nelson is in the process of selling his office and re-establishing himself more in line with his interests, his clients and his products. When his new facility opens, Nelson will be able to better approach on-the-wall-specific training in addition to the services he already provides. Though Nelson’s Instagram account is filled with seemingly complex exercises, these are his experiments and proofs of concepts that he builds into the training programs he customizes for his clients.

Though few of us operate to the same levels of strength as Alex Johnson, we each can learn a lot from the 45-minute Zoom call Nelson brings to his consultations. Nelson concluded, “I am way more interested in teaching people about why and how to train their fingers than just having them do it.” This prioritization of education is what builds the athlete into a product of self-sufficiency. The program is the parameter by which they might construct their new strength.