The Dreaded Finger Pulley Injury

From the audible "pop" to a recovery that can take months, here's what to know about pulley injuries

The cutting-edge technical free climber Wolfgang Gullich once said, “Getting strong is easy, getting strong without getting injured is hard.” Nearly all climbers will be injured during their climbing careers, it’s just a matter of when and how.

Preventing injuries is key to pushing the grades. The most common injuries for climbers in the gym is the dreaded closed pulley sprain/rupture. Very few doctors have dealt with closed pulley injuries because the injury almost exclusively happens to climbers. If you’ve had one, you know what a pain in the finger – and in the butt – it can be.

Do some research if you do suffer a finger injury to be sure you see a specialist who knows about finger as to whom you should contact to get it properly checked out. There hasn’t been a lot of literature about pulley injuries, but the book One Move Too Many by Thomas Hochholzer and Volker Schöffl has been released in two editions.

For many climbers, it was the must-read about climbing injuries, specifically pulley tears. Other books about injuries that have hit the shelves include Make or Break by Dave MacLeod and Climbing Injuries Solved By Dr. Lisa Erickson.

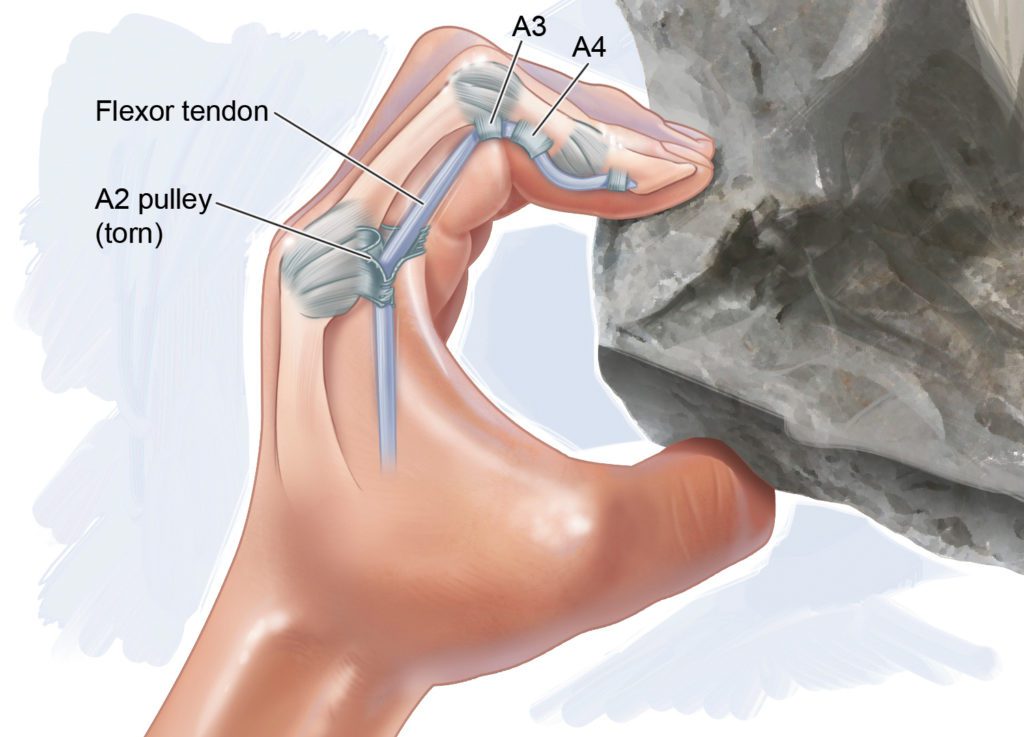

Your finger pulleys hold the tendon close to the bone and are basically a ligament that rejoins to the same bone rather than cross a joint to a neighbouring bone.

The annular pulleys (A1, A2, A3, A4, A5) hold your flexor tendons close to the bone and act as pulleys. They create a mechanical advantage that allows you finger to move through its full range of motion.

Author Volker Schöffl found that 37 (13 per cent) of 284 climbers surveyed experienced pulley injuries. And that a survey of competition climbers found more than 40 per cent experienced a pulley injury.

The most injured finger is the ring finger, followed by the middle finger. Pulley injuries are graded on a scale from Grade I to Grade IV with the worst being Grade IV. They can range from acute to chronic.

Sometimes a climber will feel a tweak and here a loud “pop” followed by pain, swelling and maybe limited mobility. The most common pain is localized and worsens when pressure is applied. Luckily, with rest and care, your pulley can make a full recovery.

Click on the two clips below to hear the sound of a pulley popping.

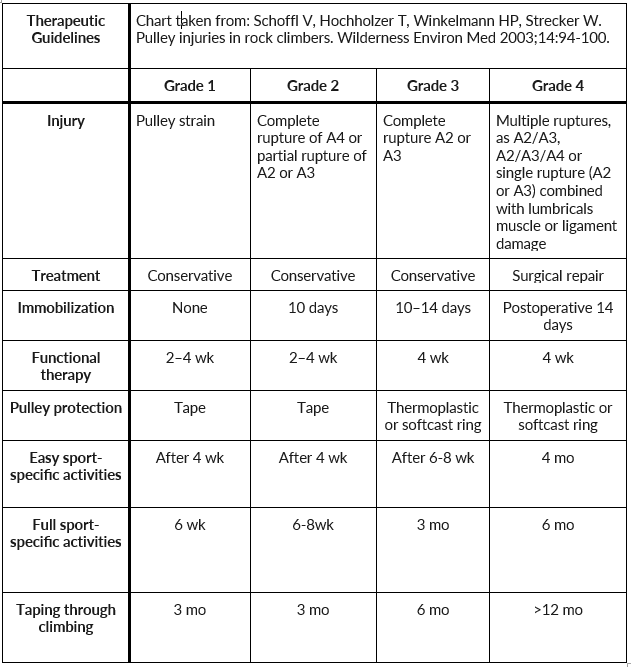

Grade I: Often called a sprain, less than 25 per cent of the pulley is torn.

How much time you take off will depend on how bad it’s torn. Schöffl and Erickson recommend some therapy (about two to four weeks) before easy climbing with tape.

Top climber MacLeod said to splint the finger with tape and to start climbing on open-handed hands as long as there’s no pain.

Grade II: The pulley is 25 per cent torn or more. Erickson and Schöffl say there should be immobilization for the first 10 days to allow healing. And then for two to four weeks there should be therapy and easy climbing.

MacLeod said to take a few days off and to return as long as there’s no pain. Keep the finger taped and splinted. He said Grades I and II are both partial tears and can heal with light climbing sessions. He stresses that without being careful, you could injure it more.

Grade III: A Grade III injury means you’ve fully ruptured the A2 or A3 pulley. If you hear a “pop” then you have a Grade III rupture, full rupture.

Schöffl and MacLeod say that a month to six weeks is needed to for functional therapy with no climbing.

And after six weeks you can climb with tape and a split for another six to eight weeks. After three months you should be good to go.

However, Erickson said to take it slower and that you shouldn’t push it before six months.

Grade IV: This is when you’ve sustained a number of injuries to your flexor system, from pulleys to ligaments. You need a surgery to fix things up.

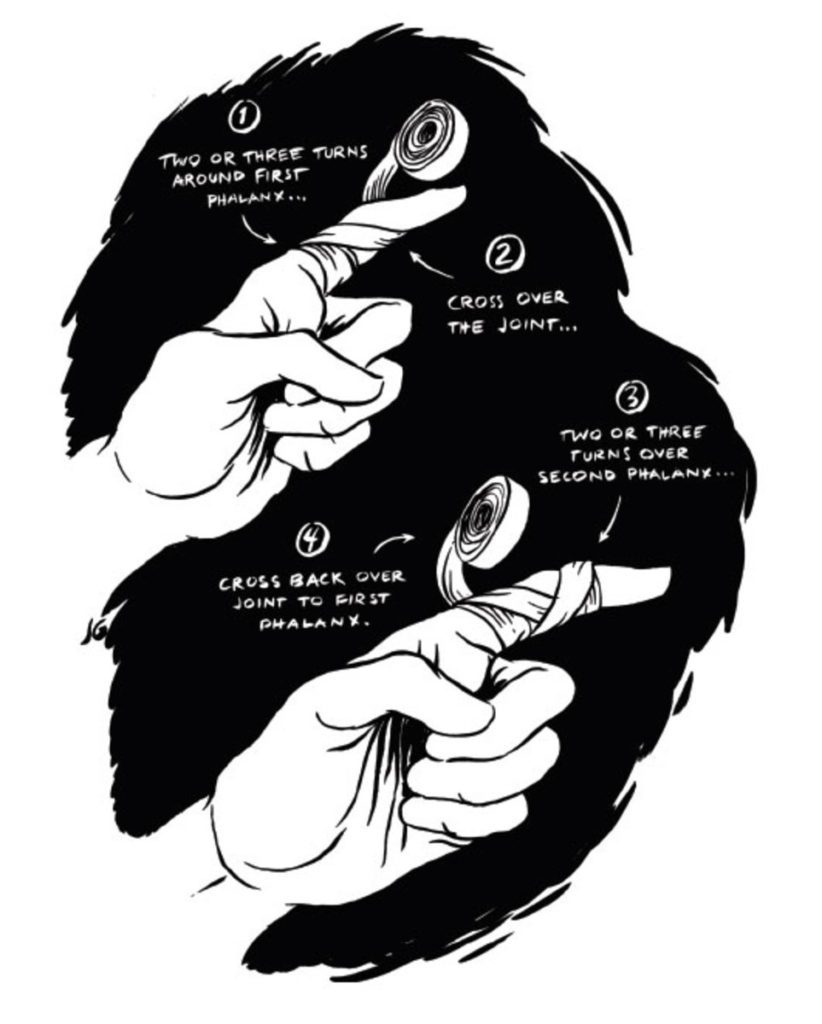

Taping Your Injured Finger

Schöffl and Erickson recommend the H-Tape method, but MacLeod argues it doesn’t offer enough support. MacLeod said tape should be used as a split to provide the support you need.

Taping to Prevent Injury

While many climbers tape their fingers for hard and crimpy projects using the circular taping method on the first phalanx (to support the A2 pulley) research has shown this provides little support.

In the illustration below by Jamie Givens, you can see how to tape your finger with one continuous strand of tape. Just don’t tape them too tight.