Five Women Who Deserve the Piolet d’Or Lifetime Achievement Award

For their outstanding contributions to the legacy of climbing

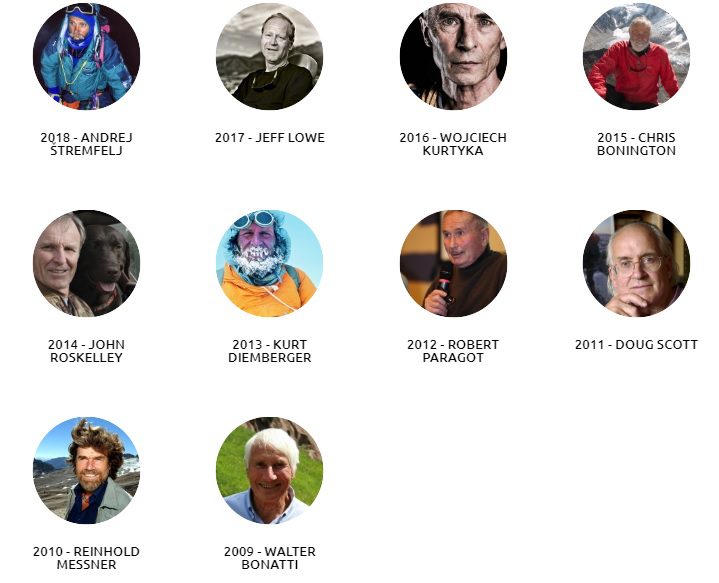

In 2009, the Piolets d’Or started giving Lifetime Achievement Awards, a great way to commemorate mostly-retired alpinists for their contributions to the sport of climbing.

Of course, many dismiss the Piolets d’Or as nothing more than meaningless awards given for dangerous climbs. And the award organization has had to deal with a number of controversies in the past.

But it seems the Piolet d’Or has shaken off most problems and with the introduction of the Asian Piolet d’Or a few years ago, it seems to be full-steam ahead.

However, the Lifetime Achievement Awards from the Piolet d’Or has never been awarded to a woman.

So far, the Piolets d’or Lifetime Achievement Awards (not including the Asian Piolet d’Or) have gone to: 2018 – Andrej Stremfelj / 2017 – Jeff Lowe / 2016 – Wojciech Kurtyka / 2015 – Chris Bonington / 2014 – John Roskelley / 2013 – Kurt Diemberger / 2012 – Robert Paragot / 2011 – Doug Scott / 2010 – Reinhold Messner / 2009 – Walter Bonatti.

Those are some of the best climbers who’ve ever lived. Their contributions to the sport are unfathomable and their ascents legendary.

However, there are countless women who have made hugely important and amazing climbs that have shaped alpinism and the world of climbing as we know it.

The following are five women who should be considered for the Lifetime Achievement Award. Others include Alison Chadwick-Onyszkiewicz, Cathy O’Dowd, Lydia Bradey, Gertrude Bell, Annie Peck and Fanny Workman, just to name a few.

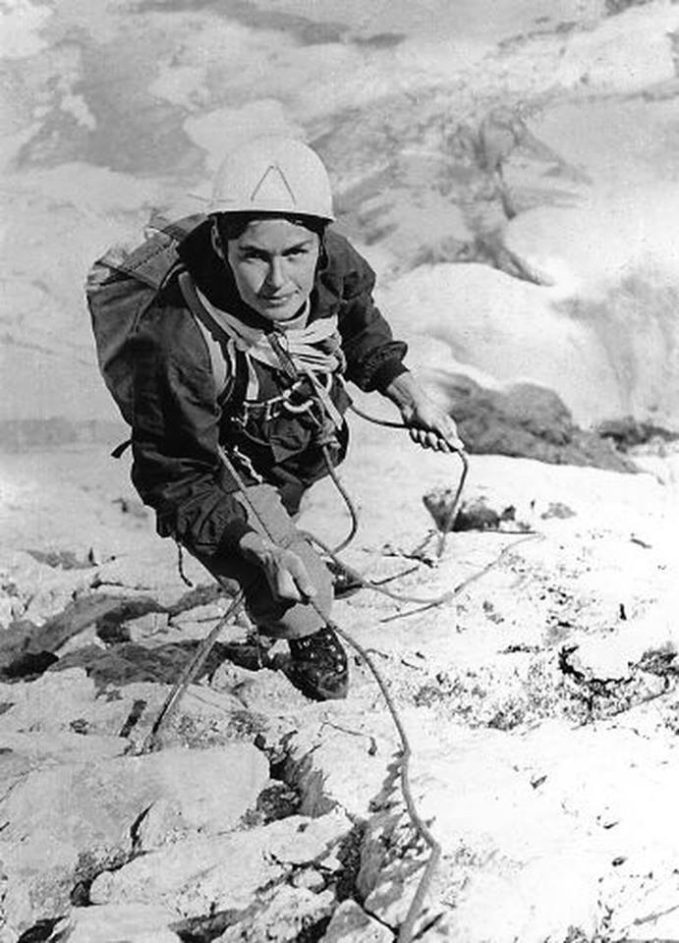

Alison Hargreaves

British climber Alison Hargreaves was the first climber ever to solo the six great north faces of the Alps in a single season.

The list includes the north faces of: the Eiger, Grandes Jorasses, Matterhorn, Piz Badile, Petit Dru and Cima Grande di Lavaredo.

In 1995, she wanted to solo Everest, K2 and Kangchenjunga. On May 13, she reached the summit of Everest without the aid of Sherpas or bottled oxygen, becoming the first woman and second person overall to do so (behind Reinhold Messner).

She then soloed to the top of K2, but died on her way down in a storm.

In her final interview, Hargreaves said that, “Everest was always at the back of my mind. It was never, ever at the front of it. I’d started to do a lot of solo climbing and then thought it would be great to try and do Everest totally independently, totally under my own steam, without oxygen.”

After her ascents of the north faces of the Alps solo in a single season, she wrote the book A Hard Day’s Summer.

In 2015, her son, Tom Ballard, who was six years old when she died, became the first person to climb the six north faces of the Alps alone in a winter season. Her daughter is also an alpinist. Tragically, Tom went missing and is presumed dead on Nanga Parbat with Daniele Nardi in January 2019.

Catherine Destivelle

French climber Catherine Destivelle became the first woman to solo the north face of the Eiger in winter in 1992. She made the ascent in only 17 hours.

In 1990, she became the first woman to solo the Bonatti Pillar on Aiguille du Dru. On the same peak in 1991, she made the first ascent of The Destivelle Route, the first route in the Alps to be named after a woman.

She was the first woman to solo the Walker Spur on Grandes Jorasses, the Bonatti Route on the north face of the Matterhorn and the north face direct of Cima Grande de Lavaredo in the Dolomites.

In the greater ranges, she went on expeditions to Trango (Nameless) Tower up the Yugoslav Route with Jeff Lowe, attempted the North Ridge of Latok I (still unclimbed) to 5,800 metres.

With Érik Decamp, Destivelle climbed the Southwest Face of Shishapangma, the South Face of Annapurna and the Losar Icefall near Namche Bazaar in the Khumbu, Nepal).

During their 1996 expedition to Antarctica, they made the first ascent of Peak 4111 in the Ellsworth Mountains before the expedition was cut short after Destivelle fell 20 metres from the summit and received a compound fracture of her leg.

In 1985, she started competition and won Sportroccia, the very first international competition held in Bardonecchia and Arco, Italy. She went on to win a number of international competitions.

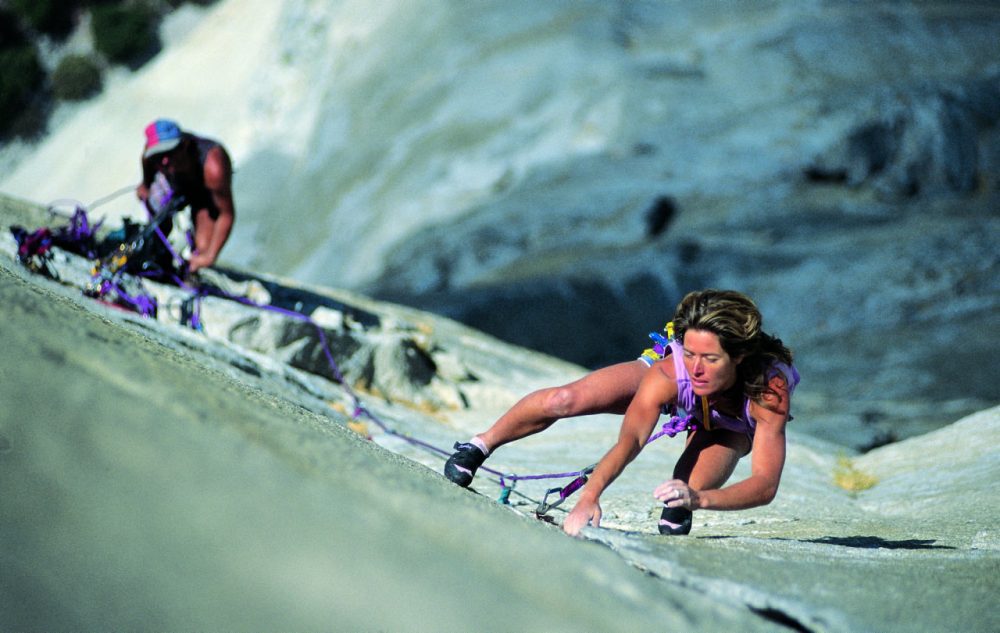

Lynn Hill

The Piolet d’Or is an alpine climbers’ award for alpine climbers, but few people on the planet have helped push free climbing on rock and in the alpine than American Lynn Hill.

Hill was regarded as one of the best competition climbers when competition climbing was just starting to become popular.

In the early 1990s, she made the first free ascent of The Nose 5.14 on El Cap. She returned the next year and made the second free ascent and did it in less than 24 hours. It’s one of the most important big wall free climbs ever.

Besides making the first female ascents of routes like Midnight Lightning V8 and To Bolt or Not To Be 5.14, she became the first woman to redpoint 5.14 with her send of Masse Critique in 1990.

In 1984, she made the first free ascent of Yellow Crack 5.12R/X in the Shawangunks and in 1989, the first free ascent of Running Man 5.13d at the same area.

In 1995, she travelled to Kyrgystan and with Greg Child climbed Perestroika Crack V 5.12b on Peak Slesova for the first free ascent; and they made the first free ascent of Clodhopper Direct IV 5.10+ on the Central Pyramid.

On the same trip, her and Alex Lowe made the first free ascent of the West Face V 5.12b of Peak 4810 in Kyrgyzstan.

In 1999, she made the first ascent of Bravo les Filles VI 5.13d A0, 13 pitches, on the Tsaranoro Massif with Nancy Feagin, Kath Pyke and Beth Rodden.

Hill’s contributions to the world of alpinism are far more important than a few snowy slogs on high altitude peaks. She was one of the best climbers of the 1980s and 1990s and inspired a generation of women.

Sharon Wood

As one of Canada’s greatest mountaineers of the 1980s, Sharon Wood is still guiding and climbing hard routes to this day.

Before talking about her ascents, here are a list of awards Wood has already: Awarded an Honorary Doctor of Laws Degree by the University of Calgary, Appointed to the Honour Roll for Outstanding Achievement by MacLean’s magazine, Awarded the inaugural Tenzing Norgay Award as Professional Mountaineer of the Year from the American Alpine Club and New York Explorer’s Club, Awarded the The Summit of Excellence Award by the Banff Centre and Awarded The Meritorious Service Medal by the Governor General of Canada.

In 1986, Wood became the first woman from North America to climb Mount Everest on an all-Canadian team.

She began climbing in the early 1970s at an Outward Bound climbing camp. Laurie Skreslet, the first Canadian to climb Everest, said, “It was obvious to me the moment I saw her that she was committed, grounded, determined, focused, persevering and overflowing with potential.”

In 1977, she joined an all-women’s expedition to Mount Logan. Then in 1983, she had her first big success with the Cassin Ridge on Mount Mckinley which “really changed my attitude. I didn’t see myself so much as a woman but as a climbing partner. I came back with a lot of confidence.”

She went on expeditions to Makalu (1984), the South Face of Aconcagua (1984) and the Northeast Face of Huascaran Sur (1985).

After the 1986 ascent, fellow Canadian climber Albi Sole said, “It’s not because she was a woman that she got to the top, it’s because she was the right person for the job”

Despite being a motivational speaker and climbing guide, Wood tries to stay out of the media spotlight, “An uncomfortable part of being a summitteer, for me, is the public and media’s one‑eyed view of heroes – our summit was the bottom line result of a series of collective heroic and selfless acts by all the team members,” she said.

“Dwayne and I stood on top because of the sacrifice, effort, integrity and heroic efforts of our eleven other team members.”

Wood lives in Canmore and continues to be a mentor for younger climbers in Canada.

Wanda Rutkiewicz

Polish climber Wanda Rutkiewicz was the first woman to climb K2 in 1986, which she accomplished without supplemental oxygen. There were 13 climbers who died on K2 that summer.

One of her earliest trips was to the Pamir Mountains with a group of men. After a bad trip due to the relationships with the other climbers, she began to lead her own expeditions, including a number of all-female trips.

In 1978, she became the third woman and first Polish climber and first European woman to climb Mount Everest.

She decided that her climbing goal would be to become the first woman to summit all 14 of the 8,000-metre peaks.

She climbed Gasherbrum III, Mount Everest, Nanga Parbat, K2, Shishapangma, Gasherbrum II, Gasherbrum I, Cho Oyu, Annapurna I and maybe Kangchenjunga.

While climbing Kangchenjunga, she was last seen alive by Mexican climber Carlos Carsolio sheltering high on the northwest face, during her attempted ascent. She was never seen again.

It is not known if Rutkiewicz summitted Kangchenjunga, but if she did, she would have been the first woman to reach the top of the world’s three highest mountains. Rutkiewicz’s body has still not been found.

Reinhold Messner said, “Wanda is the living proof that women can put up performances at high altitude that most men can only dream of.”

Rutkiewicz once said, “I never seek death, but I don’t mind the idea of dying in the mountains. It would be an easy death for me. After all that I’ve experienced, I’m familiar with it. And most of my friends are there in the mountains, waiting for me.”