Interview: The New Ontario Guidebook with Gus Alexandropoulos

For the first time in over 20 years, Ontario climbers will have a new comprehensive and up-to-date guidebook to the Niagara Escarpment. Gus Alexandropoulos is a veteran Ontario climber based in the Toronto area and one of the co-authors of the new Ontario Climbing. Editorial director of Gripped magazine, David-Chaundy Smart, recently touched base with Alexandropoulos to talk about Ontario climbing, the Escarpment and guidebooks.

Tell us about your roots on the Escarpment.

I started climbing in the mid-80s when the escarpment seemed like a significantly wilder and undiscovered place. There were definitely fewer golf courses visible when you topped out on routes. And younger readers will be amazed to hear that there were no climbing gyms.

I suspect that I got into the sport pretty much how everyone else did at that time. I read a few books (anyone else remember Mountaineering: The Freedom of the Hills or Loughman’s black-and-white classic Learning to Rock Climb?), bought some climbing magazines and eventually found a couple of more experienced climbers that made sure I didn’t kill myself.

Why does the area you are covering even matter?

Look, I’m not going to pretend that the climbing here is comparable to what you’ll find in Spain or the Red, but it is nice to have so many diverse crags within a few hours drive of Canada’s largest climbing community. It’s actually amazing how many talented climbers have come from this area. Folks like Sonnie Trotter, Ziggy Isaac, Steve De Maio all got their start here and eventually became relatively significant players out west, and in Trotter’s case, globally. Dave Lanman also started here and went on to impress in the Gunks.

And then you have folks like Peter Croft, Jerry Moffatt, Mark Leach, Porter Jarrad and Todd Skinner, and more recently Sam Elias and Jonathan Siegrist (as well as others) who have visited the area and have been impressed with the quality of the climbing.

I guess what I’m trying to say is that the while on the surface the Escarpment may not seem like an area worth documenting, it has an incredible history and still offers worthwhile climbing opportunities.

And then there are more personal reasons. I remember camping at the top of Lion’s head when you could still drive your car to almost the edge of the cliff. Or stumbling on White Bluff soon after Chris Oates and Judy Barnes had finished bolting the B-Movie wall. And more recently, spending years developing the Swamp with my wife, a few close friends and our loyal crag dog, Oz (ask me sometime about how he helped carry out my gear after I blew up my knee at the end of a long day of bolting).

Why did you decide to write the guidebook instead of letting someone else do it?

The short answer is that I had been developing a major new crag, The Swamp and I needed to document the close to 200 new routes we had established in the area. At the time, I didn’t realize what a huge undertaking it would be to write a full guidebook.

Also, as someone who’s been climbing here since the mid-80s and long before the recent access restrictions and crag closures I wanted to document the massive extent of climbing in Southern Ontario as a way of showing that this is not a new sport. In fact, many of the now closed crags were used for climbing decades before they were turned into provincial parks or conservation areas. Other than maybe hunters, climbers were the only folks using these areas for recreation. And climbers, land managers, as well as the general public, should know about this reality as it may aid climbers in future access negotiations.

That’s also why I felt it was important to include these now-closed areas as they may eventually re-open. Old Baldy is a great example of a cliff that was closed shortly after it was developed, then had access restrictions and is now open and protected for future climbing generations thanks to the work of the Ontario Access Coalition (OAC). By not documenting these areas, we may forget the valuable route history if there are access changes.

What was the process like? Guidebooks are pretty complicated these days.

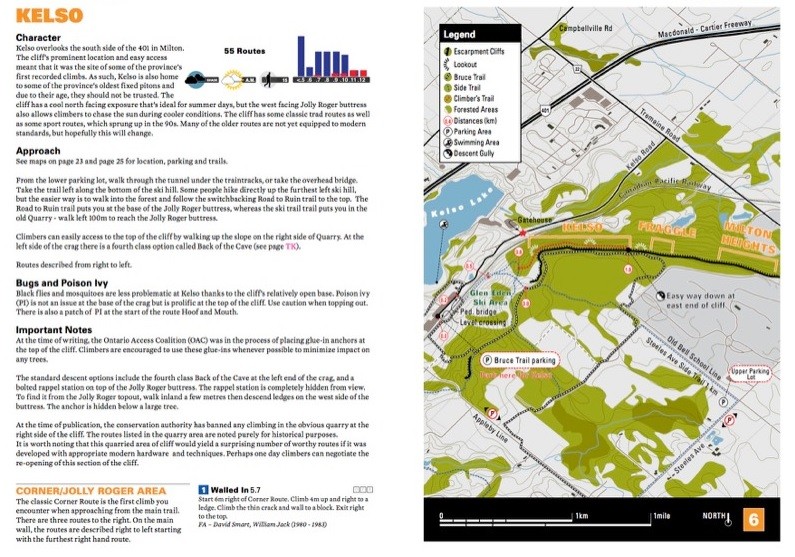

The expectations for what a guidebook should be today are radically different than what you and I first started using. In previous guides, you could supply relatively vague directions and route descriptions and that would be fine. Today folks want a level of accuracy and detail that continues to amaze me. I guess the upside to all this is that it forced us to research and create a guide that not only provides the superficial route info, but also documents the activity that eventually created much of the current local climbing.

As such, the book has become something a guidebook/history-book hybrid. It provides all the information you need for a day of cragging while also offering insight into the area’s development and the folks that contributed this growth. In my opinion, this is what all the best guidebooks should strive to achieve. Otherwise, they are simply route aggregators that only document route names and numbers and in the process devalue climbing’s rich history and culture.

Who is on your team?

While there have been a number of folks that have been immensely helpful with this project, this would be a significantly less compelling guide if Justin Dwyer was not co-authoring this book. His passion for climbing obscure routes is unmatched, and I have never seen anyone enjoy the research process as much as he does. With his work, we’ve managed to uncover a number of previously lost or forgotten routes as well as nail down accurate FA info including specific dates. It’s really amazing to see him delve into this stuff.

What was the hardest part?

Trying to document such a massive region without any previously digitized information (the last complete guide was about 25 years ago) has its challenges – no simple cut-and-paste.

It’s also difficult to accurately convey where some of the trad routes go as many of our crags lack the distinct natural features found on granite or sandstone. We initially tried to address this by photographing every cliff hoping that we could add route lines, but this didn’t pan out as the vegetation was often too dense at the base to get a clear picture. In the end, we had to go back and create overhead topos for many cliffs and employ the photo topos for the less vegetated areas. If you ever need some bad pics of Ontario crags, just drop me a line.

But I guess all this was just the warm-up for the real challenge – finding a way to document areas that have access restrictions without getting hit with a lawsuit. I’m not kidding. One provincial land manager had threated to sue me if we published anything about the climbing at a certain crag. Even adding disclaimers and omitting directions were not enough to appease him.

What do we have to look forward to when we see your book?

The guides will offer incredibly detailed and accurate route description in a very easy-to-use format. We’ve also packed the guides with interesting quotes and bit of history that are not only entertaining, but also offer greater insight into certain climbs areas and individuals. Oh, and we have some very cool modern and archival pics that truly capture the beauty of cragging on the Escarpment.

Print guidebooks look and feel amazing, do you think they have a future?

That’s an interesting question. I think digital media is cool and works for certain content, but I’m not sure how effective it is for a guidebook. From a simply pragmatic perspective, printed guides offer some pretty compelling wins: they can easily be read in bright light conditions, they offers a much larger overview of a crag without the disorienting effect often encountered when zooming in and out, and they allow you to jump quickly from different walls or crags without feeling like you are lost in the overall content.

From a more emotional (some would say nostalgic) perspective, I like how printed guides offer a physical manifestation of the areas we have climbed at or hope to visit. The side notes, folded pages and coffee stains all represent certain moments during a climbing trip, and these types of connections seem to be harder to achieve in a digital form. And then there’s the excitement you get when you open up a new guide to an area you plan to visit. I personally don’t have that same reaction with digital content.

I initially thought my perspective was just a by-product of being an older climber, but I recently spoke to a climber in his early 20s about this issue and was surprised to hear that he had a similar perspective about print guides.

So yeah, I think print guides still have a future.

Did my routes get equal or better star-billing than in previous guidebooks?

Absolutely. In fact, we switched to a five-star rating system so that we could better accommodate your contributions.

– David-Chaundy Smart’s new book Above the Reich will be released on March 24 in Canmore. For more info, visit here.