Legendary climber Wayne Merry, who was on the first ascent of The Nose on El Capitan in 1958, passed away this week. In 2015, climber Dave Benton wrote this story for Gripped after he visited Merry at his home in Atlin, B.C. Our condolences to Merry’s friends and family.

The sharp edged granite cracks held only questions above me, like rents of doubt in my desire to find a path. The stone felt fresh and new, delicate exfoliated flakes still clung to the wall in a fragile truce with gravity. I dusted off a small ledge for my toe, sank a cam into the darkness and locked off a jam to evaluate my immediate future.

A few hundred metres of cool Yukon air below blew my ropes around and I peeked over my shoulder to the corrugated turquoise ripples on the lake to far below to hear. I felt the crystals bite into my hand and listened to the whispers of the untraveled terrain around me. The thrill of being the first to experience each move mixed with the trepidation of the unknown to follow. No doubt you have to be an optimist, but maybe even more. I stretched out the rope, and then did it again.

Pondering a little more the characteristics of a climber’s psyche I was lounged back in a cluster of alder. It was a couple days later and I was belaying my buddy George, feeling the breeze and staring up at the expanse of orange and grey stone. We had left our boat on the shores of a northern lake for about an hour hike up through steep pine and alder. This unclimbed wall was about 200m tall and maybe the same wide, virgin granite riddled with cracks.

After we climbed a couple lines of my choice George took the sharp end and I found my comfy belay nest. Enjoying being off-duty I was baffled to see him choose the only spot with no cracks. He wove his way up the wall in what was his first, terrifying, lead bolting experience. An hour later all my doubts and judgments melted away with every sweet move up the face, around arêtes and over funky, knobby chickenheads. George had eyes that I didn’t, he saw a line and a possibility that I was blind to. The word “Vision” precipitated out of the jumble of talus in my head. So first ascents required optimism, vision and also the persistence to fulfill a dream.

The same summer I finally made concrete plans that had been an intention for far too long. I drove south from my home in the southern Yukon for only a couple hours through beautiful wilderness and across an imaginary line into northern B.C., to the small town of Atlin. I was hoping to meet there a climber who I had no doubt embodied the characteristics one needed to fulfill fantastic dreams.

I was about half an hour early so I drove down to the water and sat with my legs dangling over the dock. It was a beautiful sunny day with a light breeze, Atlin Lake looked like a northern postcard; blue skies, mountains, and air that felt like infinite possibility. Funny that I was wondering what had brought Wayne Merry to Atlin, I should have been wondering why so few people get to see this northern paradise. I gazed into the ripples on the lake trying to distill out what I really hoped to get out of meeting with the first ascentionist of arguably the greatest rock climb in the world, the south face of El Cap, a.k.a. The Nose.

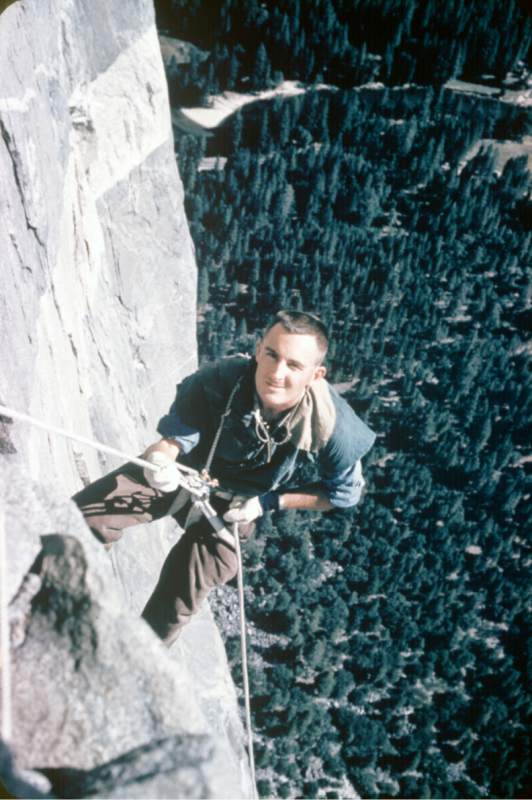

Way back in 1958 speeding up to Yosemite Valley with Warren at the wheel another crew had a vision that no one else shared, to climb El Capitan. Wayne remembered Warren as loving his fast cars and the ladies so perhaps that confidence inspired the boldest of lines. To climb straight up the highest part of the wall, the Nose, dividing the East and West faces, when no one else in the world had done anything like that before seemed outrageous. A vision perhaps conceived over a bottle of red wine in the intoxicating meadows beneath the indifferent Monolith.

My mind stretched past the route to the climbers, Wayne and the late Warren Harding swapping leads with George Whitmore and Rich Calderwood hauling loads. Where did their notions of grandeur come from in a culture that felt such an endeavor was totally impossible? What is possible though is only a reflection of our cultural thresholds. Many people seem to get locked into life, following a routine of their culture as the years slip by but for others however the norm is change itself, new surrounding, new experiences and new challenges. For some challenge is an obstacle and for others it is the elixir that makes life worth living. Perhaps this archetype is where I felt an association with Wayne and hoped for some Elder wisdom to guide me along my ever-changing path.

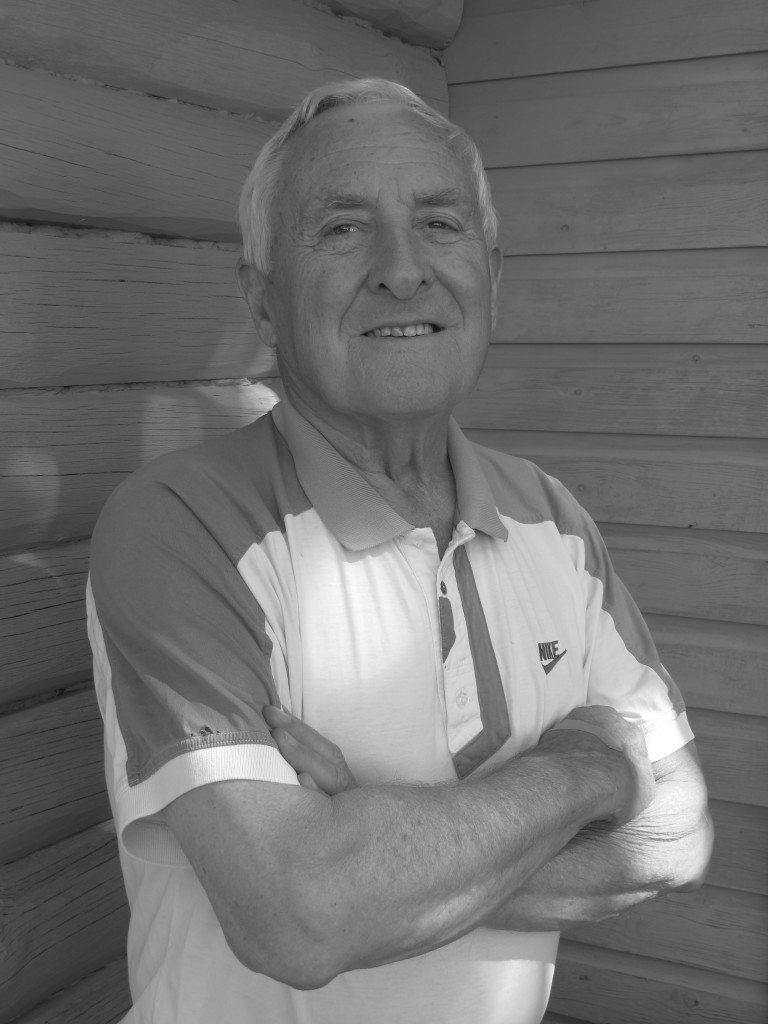

Parking beside a few boat trailers I stepped out into sparse wildflowers and tall grasses on the overgrown gravel road. He had the climber build, all these years later, broad shoulders filled out his short-sleeved polo shirt, his forearms were tanned and strong, but I was there for the eyes that glistened with stories. I shook Wayne’s hand and introduced myself. For a brief moment I reflected on how shaking hands was so appropriate, since as climbers that’s where we greet the rock.

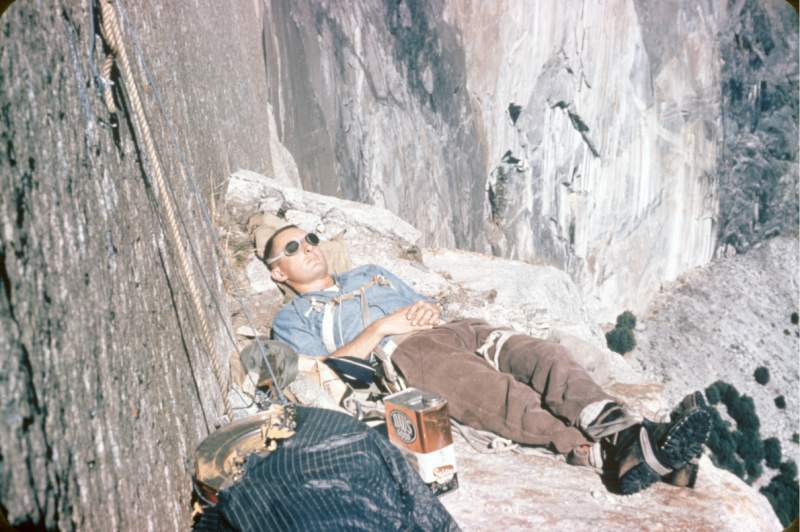

Talking to Wayne at his dining room table overlooking the carpet of forest reflected in the lake I had a hard time not contrasting their experience on El Cap to my time on the big stone. The Nose for me was a challenge pushing upwards for hours rather than days climbing on a well-travelled route holding a topo covered in notes and a full rack of tricks. Harding had spent an entire night leading the last of over 30 pitches, hand drilling hardware store ¼” bolts with a bowline tied around his waist. Seriously, a single bowline tied around their waists. Stunned by the rawness of their experience I only asked Wayne how he didn’t fall asleep at the last belay.

On my last ascent of The Nose I had a harness, camming units, fancy energy snacks, a long strong skinny rope, and a helmet, truly an arsenal of some 60 years of technological innovation. On Wayne’s ascent they were hauling canvas bags, ascending “stabilized” yachting ropes on prussiks while drinking a quart of water a day out of old paint thinner cans. “There was always a hint of hydrocarbons and I was about 15 pounds lighter by the top,” he reflected. The cracks were choked with dirt and grass where now there is only polished stone with giant flared scars of a thousand pitons.

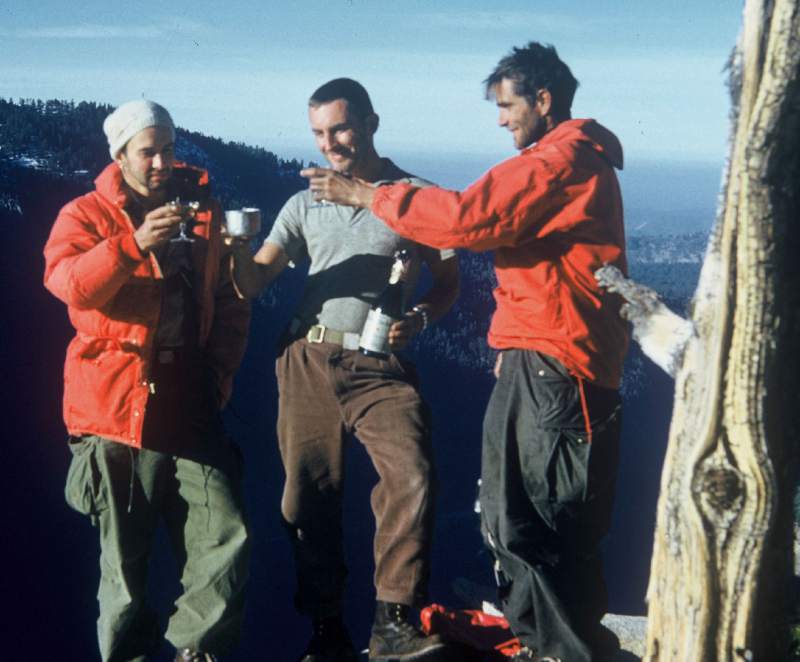

Penetrating the differences however would be the elation they must have felt, a feeling shared by the throngs who have followed in their footsteps to collapse under the gnarled pine, the final belay, perched on the rim of El Cap. Perhaps further aligning our experiences I wondered how the “brotherhood” must also have been so similar for the team to overcome the infinite challenges between the valley floor and success.

Having heard about Warren’s reputation for intensity and wondering about the personalities of the others I asked about the relationships forged on the ascent. Wayne had only fond memories mentioning how everyone fell into their roles with complete dedication. Apparently at the time Wayne’s social interests also extended beyond the wall all the way to Santa Monica.

“ We sat up on ledges in the evening and talked about life and things. I wondered when we were finished if I should ask this sweet young thing to marry me.” Wayne pointed to a lovingly framed black and white portrait from the 50s of a young woman beside the couch.

“You must be talking about me now,” came a voice from around the corner. I stood up and introduced myself to Wayne’s wife Cindy who had been quietly working on the computer.

“I decided, yeah I should, and anyways I was writing love letters to her on the wall. I brought paper and envelopes and everything so I’d seal them up and throw them down in a tin can with lots of ribbon attached to it. Our support party would pick them up, put a stamp on it and mail them to her in Santa Monica. I still have the letters.”

So now it has been almost 55 years since their relationship was sealed on the first ascent of the Nose and 40 years that Wayne and Cindy have been in Atlin, B.C. They’ve raised two sons and had a lifetime of experiences. All this lead to my burning question, “Why Atlin?” Wayne’s answer seemed to be infused with the lure of the wilderness and the challenge of the self-sufficiency.

“I’d been in Denali, I was chief ranger in Denali in the late 60s and we just kept coming north. One day a friend said well you’ve got to stop in and see Atlin. So we took a side road and I came in over the mountains and I thought holy mackerel this is Brigadoon, I’ve got to live here sometime. So after several years in Yosemite it felt like it was time to try something new.”

Back in the early 1970s, Atlin would have been a true northern town with long harsh winters and isolated from the amenities of the south, but more importantly, separated from the pointless busy pace so many of us get caught up in. When vertical camping on El Cap or just isolated by wilderness we have mental space to reflect on what truly is important in our lives without being distracted by our “to-do lists.” Moving north also involves sacrifice and I asked Wayne if he climbed much in the North.

He shifted a bit in the wooden chair and looked out the window, “That phase of life slowly became less important and other things became more important.” His one sentence summed up a realization that most people fight for decades.

Surviving in a small, isolated northern town meant being resourceful, using ingenuity, being optimistic and having vision. They did what they could for work which included Fire Chief, Ambulance Chief, wilderness trip outfitting, guiding, and quite a bit of writing for many different magazines including a wilderness first aid book. As a family they even had a stint up in what was Frobisher Bay on Baffin Island where Wayne started the Arctic College, which today is a fixture in every northern community.

“When we first came up we didn’t have a lot of money so we ate Moose, Lake Trout and garden vegetables for the first 10 years we were here and loved it. Cindy, god bless her, she came right along.”

Pioneering big wall climbing for the rest of the world had definitely been an exercise in self-sufficiency and resourceful ingenuity. The park service in 1958 was nervous about climbers and rightly so since there was no way to rescue climbers, no trained personnel or equipment. Big Wall equipment and techniques didn’t exist; the boys even pulled a wheeled cart up the wall to Dolt Tower.

It was Bill “Dolt” Freurer’s idea, (part of the first Nose team with Mark Powell and Harding); the cart didn’t survive the test of time but functioned to narrow down the options. The only manufactured pitons at the time went up to one inch so a good part of their racks were homemade.

My favourite pitches like Boot Flake and Pancake Flake were expanding dirty and difficult to protect nightmares for Wayne. I often wish I’d seen one of the original stovelegs used in their namesake pitches. Above the gaping maw of the Great Roof Wayne remembers Warren saying, “at least you won’t hit anything, except maybe me.” about his potential fall as his pins became useless, Pancake Flake stretching under the weight of it’s first human passengers.

“Did it seem really out there to just head up on El Cap?”

“Definitely, definitely.”

“Was there a lot of doubt or was there just that mindset that you were going for the top no matter what?”

“ Well I think that it became more thinkable when we looked at it in small bites. We had to with school and work coming up on weekends and holidays. Eventually we finally said screw it and headed up for 10 days in November to finish it off. The Park Service made us do that.” Over two summers and two teams the effort culminated in a committing late season push for the summit.

Having been a Valley bum myself over the years I was intrigued by what it must have been like, in the Golden Age when the canvas was virtually blank. In my head that era of climbers were the sages and gurus for the cult that followed, famed artists dancing up slabs in leather boots seemingly unaware of how terrible their gear was. They were Samurai focused in the face of the terrible consequences of any fall. Wayne reflected:

“When I first came along in the Park service in ’59 climbers were considered somewhere between Hippies and Bears. Honestly some of them deserved it, ol’ Roper at the time he was a real dirtbag, never missed an opportunity to be anti-social in terms of behavior. He eventually grew up.” Wayne smiled and sat back.

Acknowledging that Yosemite really is more than just climbing Wayne embraced the whole package. Understanding that growth was inevitable Wayne saw a need and developed the Mountain Guide service for Yosemite Park and Curry Company.

He explained, “I had to fight with them to let me hire guys with facial hair and without slick uniforms. But the good thing that came out of it is that all of a sudden people started to see these guys as people who were very responsible and capable of making a living not just bums. Climbers started to get some respect at that time.”

Contributing in a different way to the climbing community Wayne masterminded establishing the notorious YOSAR. He remembers bringing “young Bridwell” in to meet with the Rangers to work out the plan to allow the dedicated climbers to stay in Camp 4 indefinitely as long as at least half were always available for Search and Rescue. A mutually beneficial arrangement YOSAR legally supported a cadre of skilled climbers to dedicate all their time to forging routes and honing the Big Wall skills that would spread to rocky destinations around the world.

Many combined effort early rescues pioneered techniques that today are the standard for high angle practice. Wayne launched into a story about one particular rescue on Lost Arrow Spire. There were ropes everywhere, injections of painkillers, crazy maneuvers, some rangers and plenty of El Cap samurai.

Wondering about the future and looking at the mountains out the window I asked Wayne, “Someday will I be able to look at a chunk of rock and not be planning a way up it?”

Smiling again Wayne said, “I don’t think you ever lose the tendency to look at a face or an arête, or something like that, and pick out a route up it.” So if life is a first ascent then we might as well be optimistic that our unique paths aren’t just possible but amazing.

What I learned in Atlin that day didn’t come in a two-line proverb, it came from the stories of a man, a stoic weathered climber who has never feared the unknown, not just in the mountains, but also in life. Facing new challenges at every turn Wayne Merry pioneered solutions and persevered to succeed. So we can thank the visionaries Wayne, Warren, George, Rich, Bill and Mark. For one of the greatest routes in the world, but you know what, you can even thank Wayne for coloured webbing. He thought it would sell better than white webbing when he set up the Yosemite Mountain Shop.

As a tribute to Wayne, the late Warren Harding, and the boys of the Golden Age I looked for the cheapest Californian red wine to finish writing and after that some cheap Port to really finish. For as Warren said on the first ascent of the Nose, in a snowstorm at camp VI, sheltered by the sweeping upper dihedrals while passing the flask, “Any Port is good in a storm.”

– Dave Benton has been a contributor to Gripped since the first issue in 1999 with his story “Blood and Cacti.”