Updated: Lions Head’s Latvian Ledge Remains “Closed” : OAC Statement

Lions Head is a crag that is not like many others in Ontario. It requires a level of technical expertise

On July 9, The Ontario Alliance of Climbers has released a statement on the removal of the hangers and effective closure of the Latvian Ledge area at Lion’s Head to moderate climbers, reads, in part:

“On May 12, we were notified by a community member about hanger removal from select routes on Latvian Ledge. The OAC did not consult on, nor condone the hanger removal. We have made attempts to reach out to the individual(s) responsible, and while they have not come forward directly, we believe that the hangers were removed in order to reduce large group impacts and encourage regeneration of Latvian Ledge. More recently on June 25, we were notified that the Stinger Gully fixed ropes have also been removed. Though not confirmed, we believe the fixed lines were removed to discourage hikers from descending and finding themselves unable to exit safely.

“The OAC does not condone unilateral route removal. However, we acknowledge that the impact observed on the Latvian Ledge is an increasingly important issue that needs to be addressed in order to preserve access. Upon careful reflection, the OAC does not feel it is in the best interest of the long-term access at Lion’s Head to replace the removed hangers and fixed lines at this time.”

Although the OAC states that they were not responsible for the removal of either the hangers or fixed ropes that had been left in place on a steep descent gully, many climbers interpreted the OAC statement as an endorsement, for better in the eyes of some climbers, and for worse in the eyes of others, of the route closures. Climbers who frequented the ledge were surprised by the timing of the removal in the midst of a climbing season when access to other moderate climbing areas, such as Rattlesnake Point was severely curtailed by Covid-19.

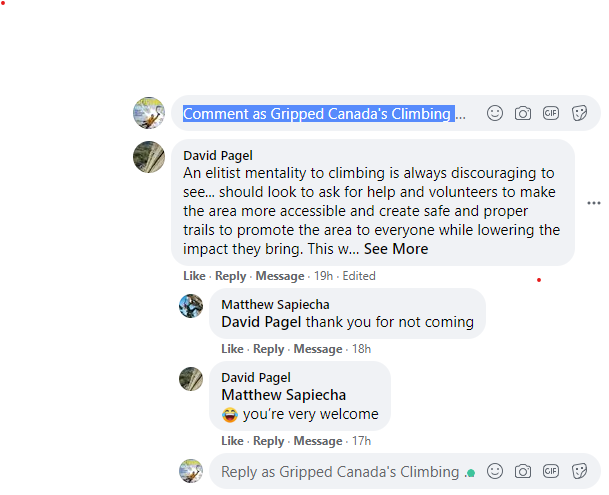

Some more experienced climbers thought it was overdue. They argued that the presence of moderate climbers was an unwelcome distraction for hard climbers and that the Latvian Ledge climbers exhibited hubris in coming to an advanced cliff. In one post, a climber invited moderate climbers to come to watch them climb at Lions Head, but not to climb themselves. Another individual claimed to have removed the hangers and then removed his post as well, after being surprised that comments on social media were visible to the public. Some objected that the removal was an elitist coup de main based on the idea that harder climbers had the right to ban other users from public lands. Others thanked climbers affected by the chopping for not coming to the cliff.

There is no doubt that the ledge, like many other ledges at Lions Head, has seen heavy use and erosion and unlike eroded ledges at the cliff’s hard climbing zones, is easily visible from the top of the cliff, thus making a bad example of climbers’ leave no trace ethics. Also, there have been incidents where a lack of technical knowledge on the part of climbers visiting the cliff has gotten them into situations where they required rescue or assistance. Removing the routes on Latvian Ledge, some argued, would discourage unprepared climbers from visiting the area and getting into trouble.

Latvian Ledge, a slabby section of rock on a mostly overhanging cliff, was first climbed by John Weir, Michelle Lang and the author in the early 1980s. It was named by the author after the heritage of Weir’s wife, in exchange for a pie. A few years later, sport routes were added by Mark Bracken and Chris Oates. They deliberately over-graded the climbs to discourage moderate climbers from visiting. But moderate climbers and even instructional groups saw through the gambit and began to visit the ledge in increasing numbers. The easy climbs, accessible by one short rappel, the unexposed feel of the ledge below the wall, the spectacular setting on Georgian Bay and the capacity of the area to absorb groups increased its appeal. At the same time, Lion’s Head attracted gym-trained climbers to its overhanging rock. Sonnie Trotter’s Forever Expired, at 5.14d, remains one of the hardest climbs in Canada.

The Latvian Ledge was one of the first areas where moderate climbers congregated outside of Milton, near Toronto. Some brought habits like leaving topropes in place all day and arriving in large groups, which included climbers not usually considered experienced enough to climb at top-access areas like Lions Head, where bad weather could necessitate escape with mechanical ascenders and stretched anchors across hiking trails. Concerns about the safety of these groups (admittedly often tinged with elitism) led to some climbers, including the author, suggesting removing the hangers from the routes. In recent years, as the demographic momentum swayed in favour of less experienced climbers, however, it became clear that new climbers needed safe routes and concentrated places to climb such as Latvian Ledge and many climbers (including the author), changed their viewpoint and saw the importance of providing them with suitable areas. With ongoing use, however, environmental motivations for reducing traffic at Latvian Ledge were voiced. The community at large was surprised, however, by the unilateral action of the person who removed the hangers.

Greg Williamson grew up in Wiarton, not far from Lions Head and has been climbing at the cliff for some 28 years and up until the hangers were taken, still visited Latvian Ledge. “It’s tough,” said Williamson. “I don’t want to say the wrong thing, but to me both sides [for and against the removal of the routes] are right. I see where it is elitist. The grade you climb has nothing to do with competency. And yet, 90 per cent of the problem from these routes is that they do attract people who haven’t got the skillset to be at Lions Head.

“The problem isn’t just at Lions Head. There are so many people who climb easier grades now, climbers are better. [At Lion’s Head] they predominantly go to Latvian Ledge, sometimes in big groups of 5-15 climbers. I see how [the hanger removal] could come across as elitism, but the general feeling is that so many people see a problem, but no one knows how to address it. I’ve discussed it with other climbers over beers, I always thought the best solution was a permit system, then people are invested and wouldn’t be so casual.”

“It just seems to be that climbing just happens to take place outside for some people,” says Williamson. “They’ve got no outdoor etiquette. I find that personally frustrating, 25 years ago, things were different.”

Williamson fears, however, that “the response [to the removal], has been worse than the problem.”

“It isn’t for one person to decide. Just because I live here, I don’t have the right to decide,” says Williamson. “Personal opinions don’t give me the right to decide for the whole climbing community.”

As for the future? “Really, at the end of the day,” says Williamson, “it’s only the hangers that were removed.”

The OAC, a volunteer organization run by climbers, also seems to have been surprised by the removal of the hangers. Mike Penney, a talented climber who has been involved in access work with the OAC for eight years, volunteers 8 to 15 hours a week for climbers’ access and has participated in past successes such as securing climbers’ access to Old Baldy and retrobolting Rattlesnake Point. Now he focusses much of his effort on Lion’s Head. “I love climbing at Lions Head, it’s a wonderful place,” says Penney. “I’ve been climbing here for many years, and I’m very connected with the climbing and wider community.”

“Climbing is not officially allowed in Ontario Parks, with the exception of Bon Echo. At Lions Head, it is just tolerated, and by that nature it is tenuous, that’s one of our biggest challenges,” says Penney. “At the place we enjoy so much, we are not officially allowed to climb, just tolerated. One day, we may be permitted to climb there officially. Outside of that, we have the challenges every user group has and that includes making sure we have leave-no-trace ethics.

“Lions Head is a crag that is not like many others in Ontario. It requires a level of technical expertise,” says Penney, referring to the knowledge of self-rescue and experience required to climb safely at the cliff. “There have been incidents with accidents, minor and not so minor, and rescues. A classic challenge is someone falling on an overhanging section and being unable to get back on and needing to be rescued. The cliff is a difficult place to navigate. It takes a long time to learn the cliff. Another classic mistake is rappelling into the wrong route.”

In contrast to some statements that followed the removal of the hangers, Penney is understanding of the needs of beginners. “All of us started somewhere,” he says, “I started climbing fairly late,” says Penney, who began climbing at age 26. It’s not fair to split our user group into two groups and say only one group is the problem. It’s fair to say Latvian Ledge was heavily used, and from those in the wide network of community, even just as wide as we can reach, it seems as though that area has seen a lot of problems. It has been troublesome.”

His advice for climbing a Lions Head is the same as for other areas: “Know what you are getting yourself into.” Further advice from the OAC on climbing at Lion’s Head is available here.