Why Some Mountains Shouldn’t Be Climbed

"We may gaze, but we may not touch"

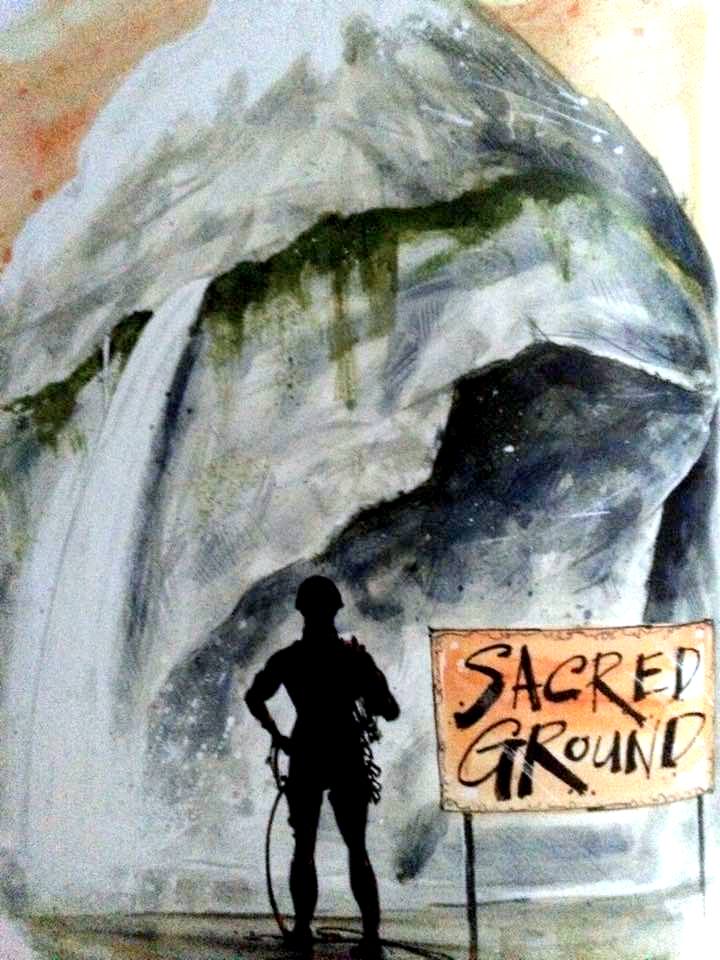

The following was written by John Kaandorp for the August/September 2014 issue of Gripped magazine about why some things shouldn’t be climbed.

After 35 years of shinnying up steep rock and ice and two walks through the Himalayas, I am coming around to the view that climbers should not clamber and touch everything on the planet. This may not be a popular view. As climbers, we prefer to have unlimited access to everything within our grasp: buildings, boulders, cliffs, walls, waterfalls, mountains and their summits. To walk at the base of a wall or in a valley below a mountain is good, but touching them is better. Who has not felt compelled to reach between the wires of a fence and touch the flanks of a horse, or between the “bars” of an iron or glass cage and feel the coiled strength of a tiger? But naturally, we do not.

This idea of keeping some things off limits to tourists and climbers is not new to the Anangu people of Australia. When people ascend Uluru, the world’s largest monolith in central Australia, they offend the Anangu people. For them Uluru is not just so much stone but a palpable life force connected to ancient aboriginal knowledge known as Tjukurpa. The wisdom of Tjukurpa is understood by them to exist at the base of the mountain and is known through the trees, stones and dirt found there. Their power and knowledge is not on Uluru’s summit, so for the Anangu, there is no reason to climb. People are informed of the cultural sensitivities before their ascent, both by signs and the Anangu themselves, but the sacred gatecrashing goes on. Is it any wonder that in the local Pitjantjatjana language they refer to climbers ascending Uluru as Minga or ants.

Tse’Bit’a’i is the Navajo name for Shiprock, the volcanic plug in the American southwest that resembles a bird with folded wings. First climbed in 1939 by four Americans, Shiprock has been closed to climbers since the 1970s after a fatal accident. The nearby Spider Rock and Totem Pole have been closed since 1962. The prohibition of climbing on Navajo lands is informed by the sacredness of the landscape and the taboos that are created when there are climbing accidents. Despite this, many clandestine ascents continue to be made.

The Himalayas have the greatest density of peaks that are off limits to climbers. We may gaze, but we may not touch. In 1994 Bhutan banned all climbing above 6,000 metres, and then in 2003, in deference to spiritual customs related to Mahayana Buddhism, all climbing was stopped. In western Tibet, the 6,714-metre peak of Mt. Kailash is regarded as the home of Shiva, the Hindu god of destruction and regeneration. Tibetan Buddhists believe that Milarepa flew to the summit in the 12th century and resides there in perpetual and supreme bliss. They believe that to touch Kailash is sacrilegious and any attempt to climb it would be fatal. Instead, Hindus, Buddhists, Jainists and Bon pilgrims walk or prostrate themselves around the 32-kilometre base of the mountain. It is believed that Kailash is the pillar of the earth and the epicenter of the world’s mandala.

My most intimate experience of a sacred mountain with a “no touch” philosophy is the shapely Khumbi Yul Lha, which towers aiguille-like above the Sherpa villages of Khumjung and Khunde in eastern Nepal. Although it is dwarfed by other Himalayan peaks on the horizon such as Everest, it is astonishingly beautiful and complex as it looms over the maze of stone lined walls and stone houses below.

Taschi Lama, a student of Buddhism, helped me to understand the significance of the peak for the Sherpa people. He explained that Khumbi Yul Lha is home to their protective deity Khumbila Terzen Gelbu who rides a white horse, while his wife Thamserku lives atop a peak across the Khumbu valley. In July, Sherpas celebrate Khumbila at the Dumji festival in the nearby village of Pangboche with dancing, singing and rituals.

The fang-like peak of Tabuche, 6,495 metres, is also celebrated with the Tabuche dance and is currently being petitioned by local Sherpa residents to be off limits to all climbing scrambling or touching.

In Ontario, there are strict policies about what can be climbed on the 700-kilometre long Niagara Escarpment. For instance, at the very tip of the escarpment, in Bruce National Park, only bouldering is permitted on the limestone boulders near the shoreline. Roped climbing is neither encouraged nor tolerated. In part, climbing is not permitted because the geography is a sacred sanctuary for the eastern white cedar, some of which are reputed to be 1,600 years old.

In general, climbing on the escarpment is viewed as a “non-conforming” activity but is currently tolerated in popular areas such as Lion’s Head. A 2015 Niagara Escarpment Commission plan review is suggesting that new route activity be limited to sport-routes 5.10 and harder, which tend to follow walls with less damage to fragile flora. They would also like to see permanent anchors used to limit damage to the rock and cliff edge.

I enjoy exploring a world knowing that not everything is commodified, for lease or rent or for sale. We may boast about adding value to a service or a product before cranking up the price, but perhaps not letting climbers ascend a certain very few cliffs and peaks around the world is a way of adding value by doing simply nothing. It is a pleasure to know that some mountains are free of via ferrates, trails, bolt ladders, chalk dust, fixed ropes and porta-ledges.

In Nepal this spring, while sitting on a very cold wooden floor and after listening to the morning chanting and praying in the Tengboche Monastery, Taschi Lama reassured me that Khumbi Yul Lha has never been climbed and never will be. To him, this knowledge was as clear and concrete as the mountain soaring behind him into the cerulean blue Himalayan sky.

As I stood with Taschi sharing a cup of sweet tea below his sacred Sherpa mountain, I thought to myself, “No mindless ants on Khumbi Yul Lha, no mindless ants.”

– John Kaandorp has made a number of first ascents in Ontario over the past 40 years and still frequents the local crags. He is a regular contributor to Gripped.