Belief: the first ascent of Mount Louis, by Jerry Auld

Canmore-based Jerry Auld is one of Canada’s foremost mountain fiction writers who shared his story about the first ascent of Mount Louis in the Canadian Rockies.

Our new online column called “Portrait of a Mountain” focuses on the climbing history of different Canadian peaks every week.

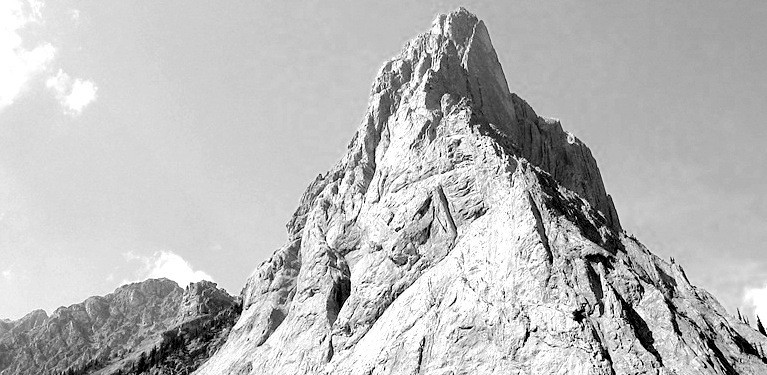

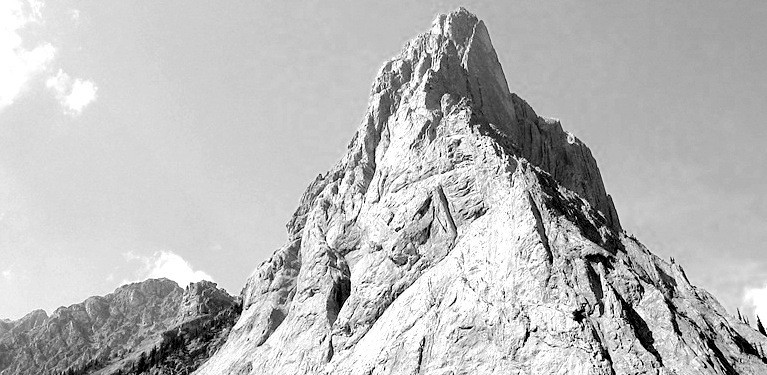

Our second peak was Mount Louis, the iconic mountain in the Sawback Range near Banff. Jerry Auld has long been fascinated with the history of early ascents in the Rockies and penned this story about the day Conrad Kain and Albert MacCarthy made their legendary ascent.

Belief: the first ascent of Mount Louis

By Jerry Auld

The night before, Conrad Kain, the lone Austrian mountain guide said they would go for a picnic “just to view the scenery.” Kain made it clear among those at the Alpine Club that night. It was early July, 1916 and the snows were still blocking the high passes and choking the big rock faces. Kain wanted it to be known that he was not going off into the King’s own country unannounced, however the peaks called.

Kain knew he was a minority. And that he was being watched.

The second-floor windows at the Alpine Clubhouse in Banff, on the skirts of Sulpher Mountain, were cracked ajar to the crisp chill of the late spring morning air but the curtains did not shift. Kain walked carefully off the porch and around the back. He was used to disappearing. He’d seen the young men unloading from the train carriages at the station when he himself waited for a client, saw those young soldiers helped down, here to take the mineral springs to sooth the ache of shrapnel in their sides, or the mountain air to ease the damage of chlorine gas in the lungs. At that point Kain was invisible – the boy’s eyes were all for the glory of the mountains. But once they’d been in the streets of Banff for a while, and he was pointed out to them – this short Austrian guide – then Kain appeared to them and he saw their distrust and sometimes their hatred.

And there was jealousy too, lots of that. He was off picking the highest plums in the Rockies while Canada’s finest were off being blasted to bits or drowning in their trenches. Nobody seemed to mind the Swiss, of course, the Swiss Guides were Swiss, and they were neutral. Even the Swiss resented Kain a little, thinking he took too many chances with his clients, believing him untrained and rash. But at least that was an old-school condemnation – rarely spoke – and Kain as a shepherd and poacher and a quarryman from the Tyrol was used to the silent disapproval.

It was in the stables, under his outstretched palm that the ponies didn’t denounce him. His movements were being watched, you see, but just not at that hour. He saddled them, and packed into their bags the lumpy canvas sacks and led them out in a slow train to the steps of the Alpine Club, where the others (the Stones and the MacCarthys), silent as new snow, descended down the wooden steps and walked off with him.

They all knew their horses, the ones they’d ridden for the last week or so, and the horses knew them, and didn’t whinny loud, affected by their handler’s solemnity. The party joined together slowly, quietly, comforting the horses, and walked them silently down the road to the bridge that spanned the Bow river, and there they mounted, and rode across the stone bridge and in single file made their way down Banff’s Main street.

They were pleased that the street was empty save for a milkman’s trolley, a few slinky cats, a horse broke from his tethers. None that would discern a climbing party from a fishing trip. The coils of hemp were safely at the bottom of the food rucksack anyway. The Americans, all of them were save Kain, were relived as well. They were not called interlopers. Instead they were admired, welcomed: their money and culture appreciated. It was not the peaks that they were tacking while the native husbands and sons are being slaughtered, it was that they were on vacation: idle while the “civilized” world tore at itself with its industrial jaws.

“When will you join the cause? When will you help us?”

They were asked again, and again. It made packing for the quiet mountains a pausing, existential exercise. It nagged at Albert MacCarthy, a naval man, an officer who saw action against Cuba in the Spanish-American War eighteen years prior. He pulls too hard on a drawstring at times, but otherwise his face is stoic.

It was six AM when they left and six-thirty when they crossed the bridge and though that seemed painfully slow they didn’t wince when a dog barked at them from a brick-walled canvas tent, their eyes shifting toward the sound but their chins staying on their horses. The sun was coming up and that was a bigger concern. They hurried to remove themselves from the Main Street and crossed the railway just east of the station.

Kain had stood on that very same platform and seen the carriages lurch to a stop – their iron bogey wheels crunching the dust on the rails in a rolling industrial vise – and the open windows stuffed with gaping Ukrainians, Germans, and yes, Austrian internees. Not really prisoners of war, as they’re not soldiers, but enemy aliens. Kain won’t look at them, not that they are looking down. They were unloaded for the wagon ride to the Castle mountain work camps. Kain hopes they won’t talk, not in German, and remind others of his own accent. And even though he would like to climb there, he doesn’t. He doesn’t go near that area of the mountains.

Bess MacCarthy, who has a soft side for all things, has seen the way Kain shies from this. “Oh, Conradl,” she said using the diminutive form of his name, like he is her child. “Don’t let them get to you! They will believe what they must, but we all know that’s not you.”

Conrad Kain smiled under his moustache and nodded. The damned war should have been over long ago.

All the women loved Conrad Kain. Margaret Stone, whom was devoted to her husband, still affected this clandestine crush as a stage whisper – He’s not large, as benefits a climber, but he is tenacious. Always sneaking off! Well. What is better than a man that will fight for you, I should declare, is one that will never give up.

On the other side of the heavy steel tracks they stopped.

Winthrop Stone, the professor cum head of Purdue University said:

–No-one’s after us. We’re good.

His wife, Margaret, sais — As long as there is no one there.

She says it in German, without thinking, and she sees her husband’s back stiffen just a touch under his jacket, but he doesn’t turn on her. Margaret knows he won’t speak German in public, and wishes they would say more when alone, but she also knows the risks. Margaret met Winthrop at the University in Göttingen, when he was studying there – the suave American chemistry professor. Margaret Winter is his second wife, but never-the-less, she is German. She has practiced saying her maiden name quietly for years now, replacing the “Vin-ta” with a soft starting double-u and a hard ending r, drawling as they did in the western mountains.

Winthrop won’t even speak German to Conrad, and not just in deference to the MacCarthys, but in solidarity to the cause, and perhaps in fear of the mob. He won’t even allow himself to hum the latest tune, even though ironically the German ones, like “Auf Wiedersehen” are some of the most popular. It saddens him, as they turn west and ride the wagon road in the early sun and steaming breath of the horses in the cool dips that he is cut off from the great universities of Saxony and Prussia. And the stinking lies of the propaganda that settles bitter in the morning like whiffs of juniper and bearberry. Winthrop’s brows slope downward at the sides, over his eyes. Margret said he looked sad. – We must carry on. She told him, quietly in the night. Everyone is sad. It pervaded them. However lucky they were to be away from the fighting, the grinding, but Winthrop can’t help but to think of his friends and Margaret’s family.

The horses skirted the marshy flats of the Bow River and the Vermillion Lakes as the sun was full above Mount Rundle and they turned up into the aspen groves at the foot of Mount Edith. Kain directed Winthrop and Albert to the rear and brought the women in between and lead the way. He went slow, picking a way through the trees. Kain had been trapping and hunting and now guiding in the mountains his entire life and he relaxed under the spruce boughs and down the quiet valley between Edith and Mount Norquay.

Mid-morning they arrived at Mount Louis in a small meadow at the base of a large scree fan. They tethered the horses to feed on the alpine grasses and laid out blankets and unpacked the baskets. The day was warm, promising to be hot, and the sky was a solid unfocused blue. They ate scones with margarine and beef jerky and goat cheese. Albert MacCarthy stood within minutes of eating, spying the long vertical striations of this Mount Louis, this inaccessible pinnacle. Impatient with the sitting, with the talking, with the story so far. This can’t be just a picnic, not on such a fine day. – Let’s go poke our noses in that.

Dr. Stone waved him off. Dr. Stone loved the mountains, but he loved Margaret most of all. She was his second chance, someone to grab a bit harder. His first wife, also German, abandoned him and their two sons and ran off to join a cult in India. So much pain, so much loss.

Now the illustrious president of Purdue University lounged like a student on the bristling meadow, in the sun of the first full summer day in the mountains and was content to lie still for a time. The ground here didn’t thump and shake and leave your legs feeling sideways.

Bess MacCarthy sat on a blanket with her legs tucked up and close to Margaret, weaving an impromptu crown of wheat grass and studiously avoiding her husband’s eye. Margaret was poised quiet under her trilby hat, tiny wisps of hair curled out unnoticed by her. She had a soft voice, soft eyes. It was that kind of softness that drew one in toward her, that ever deepening softness, like a cliff edge giving way. Everyone was a little bit in love with Margaret Stone.

Kain was already pulling together his kletter sack, freeing the rope and twisting it for carrying. There wasn’t not much they needed.

And then there was just the two of them, moving quickly up the side of the talus fan and onto the rock apron below a sheer diamond-shaped face. Keeping up with Kain was MacCarthy’s sole concern. The rock was loose and they scrambled over large bulges, everywhere the thin layers of broken rock revealed another bulging layer beneath – like bubbling onions. The rock seemed hard, solid, but to Alberta MacCarthy it was not inconceivable that the iron battleship grey stone was not worn down by glaciers but instead had bubbled upward and solidified. He had seen hardened surfaces buckle and liquefy. He knew nothing was truly solid, if you focused enough force against it, everything would yield.

They skirted the slabs and worked their way up and to the left, stepping along sloping ledges and toeing up broken steps. Then on a large ledge the wall above them rose unbroken and they moved left toward a corner, the prominent ridge that separated the east face from the south. It was all in the sun and the flat diamond-shaped slabs of the upper mountain we apricot and brown.

MacCarthy looked up. – Do you think it will go?

Kain was motionless, balanced on fingertips, peering around the corner.

— Ja, Herr MacCarthy, I believe so. Why not? It is only a picnic.

MacCarthy smiled, hearing joy in Kain’s throat.

They scrambled across barren slabs of grey limestone as the mountain on the south side dropped off vertically below their feet. Kain crossed over to the south face and led cautiously up the deep groves in the up-thrust strata, in between the mountain’s thin ribs. Eventually they came to a platform with blank walls leading to the summit. They were close, but it was out of reach.

There was, however, just up a short steep pitch, a shoulder-width slot where the softer rock had worn out from the stronger ribs. MacCarthy got a thrill – the same one of dread and excitement before battle. He dug for his canteen on the barren parched rock and wet his mouth. The chimney before them rose up to the summit. It was dark, like a trench had been dug in the mountain. They pushed in for ten feet. The back was sheathed in rotten ice. On either side were two perfectly smooth walls. And far, far above: a narrow slit of hot blue sky, like the base of an old-fashioned keyhole.

Kain and MacCarthy were the same stature – not overly tall, with rather narrow houlders. But both had been forged hard in life’s furnace. MacCarthy’s face was especially, his looked like metal dented in over the girders of his unbreakable skeleton. They climbed well together because they had the same stride, the same reach. You have to get through the trench if you’re going to finish this, thought MacCarthy, looking at the coil of rope on Kain’s shoulder.

— We’ll leave the rope, Herr MacCarthy, said Kain. — It will only hinder. All we have is courage.

That’s what will bind us, and it must not break, not on this.

They left the still unused rope, and their packs, on the platform and made their way up to the chimney and pushed into it, hunching their shoulders inward, scraping the icy smooth walls. Ten feet in and the back of the slot was dirty ice.

They stood in the dark with the cool drip-drip, so close but without a hold of any sort. Their curiosity compelled them, and although not physically attached, they were irrevocably bound.

Kain wedged his back on one side and then inched his knees up on the other, until he could pressure his hands down behind him to elevate his hips. It was a long way toward that opening of the unknown, and the only thing that held him between the walls was the constant pressure from palm, back, and shin. That, and the need to see the light above, to elevate, and to stand on top. There was no rest, and any slip would be unrecoverable.

MacCarthy said: — This is the kind of perfect chimney one hears of, Mr. Kain, but never sees, and I dare say, one might never want to, again!

Kain said, looking down, his voice heavy in the close echo: — It is an adventure, Herr MacCarthy. He moved again, pinched in the palms of the mountain, humming the popular ragtime refrain “Canadian Capers.”

Mack, a lieutenant commander, started up. No point in waiting, turn and move toward the sound of the guns, he thought. But this was like war to him, locked in a vise between immovable positions where one just had to fight it out and see who prevailed. There was a time for decision and a time for action and when it was the action you cannot think of other options. There was just the walls, pressing, the icy black walls, and his own strength pushing back, pushing upward, and pushing slowly to the surface.

It was hard to breath – the knees pressed up high, holding the shoulders back – but it could be worse Mack knew. They could be dead.

Then, near the top, the chimney pinched again, narrowing until they wriggled up with their legs dangling, only the squeeze and expansion of their arms inching them up.

Finally, the top: a pile of broken stone to wriggle out on without slipping back.

— Bergheil, whispered Kain.

He stood on the small broken top and heard the grunts of MacCarthy coming up the dark narrow cleft. A guide should always be blessed with such able clients, Kain thought. He helped

MacCarthy out of the slot and, as happens in the mountains, their perfect day turned suddenly to rain, then sleet.

Herrgott, there is no rest, said Kain, building a quick cairn and inserting his tobacco box with a torn note of their names and date under the stones.

MacCarthy looked at the sea of brown and grey peaks swathed in the clouds, many trailing long white scarves. He thought they resembled a naval flotilla in jagged dazzle paint. He remembered the Spanish Fleet off Santiago de Cuba, trying to break out of harbor before the American’s could build the fire in their boilers and get up enough steam to give chase. They were hunted down and sunk or the Spanish cruisers were fired upon until they exploded as his crew shouted “Remember the Maine, to Hell with Spain!” Men were drowning as others chanted. MacCarthy wanted to forget all that. He wanted to think about men testing themselves against the impassive mountains, and not against other humans.

MacCarthy spied the small camp of safety below. They looked tiny, his wife and friends, so far away. He could cover them with his hand. Winthrop was like an busy ant, disturbed.

— Likely Winthrop is worried, said Albert MacCarthy. We should signal him. Kain yodeled, a piercing sound like a marmot surprised. Winthrop stopped, they were looking up. Kain waved. None of them moved down below.

MacCarthy realized that the only way home is back down through the trench. He looked down its slot, barely leaning over its loose funnel entrance.

— Good thing the rope is below, I’d hate to hang myself if I fall.

They eased themselves back into the chimney. Aware but not thinking overtly of the spot where it opened wider with a hundred feet of shaft below. The human body was built to go upward, and the descent proved more difficult, though neither showed fear. Their fear was pushing back from their pressure holds on the polished blackness at their necks and the small of their backs where the hollow was against the cold stone, or at their palms, and always against the dark depth before their eyes.

Kain then picked their way down and back along the tiny ledges with scanty finger holds in small cracks and sheer drops. They’d long been out of water, long ago burned through the scones. They traversed back slowly, under the complicated ribs that made the mountain appear to be constructed of compressed slabs, glued together, upright, like slices of stone, thin as pastry, ready to be plucked out by a giant’s hand. A tombstone quarry. The thought passed and was gone. Just as they did on the bony sides of Mount Louis. Kain moved down in that way one does when one smells water. He unerringly retraced their route down vertiginous and similar grooves, and spanned around ribs without looking down.

The others waited with the horses ready at the height of the scree and hailed them amid hugs and soft cheers. MacCarthy smelled Bess’ hair like only since he returned from sea and he knows at that moment that he will have to be going back. He sat his horse close to her. They had no lantern and it was a long way back to Banff, but they were buoyed with the success.

Mount Louis was a monolith rising dark before a brass sky. Albert and Conrad from time to time on the way up to Edith pass stole glances back.

— Ye Gods, Herr MacCarthy, said Kain in absolute wonderment. — just look at that; they never will believe we climbed it.

Read Jerry Auld’s story Disbelief: the first ascent of Ha Ling Peak