Ben Zartman: “I was the ultimate climbing and sailing dirtbag; I had no car or money”

A fixture in the boulders of Yosemite Valley during the 1990s, Ben Zartman lived off $3,000 a year and climbed full-time before sailing all over

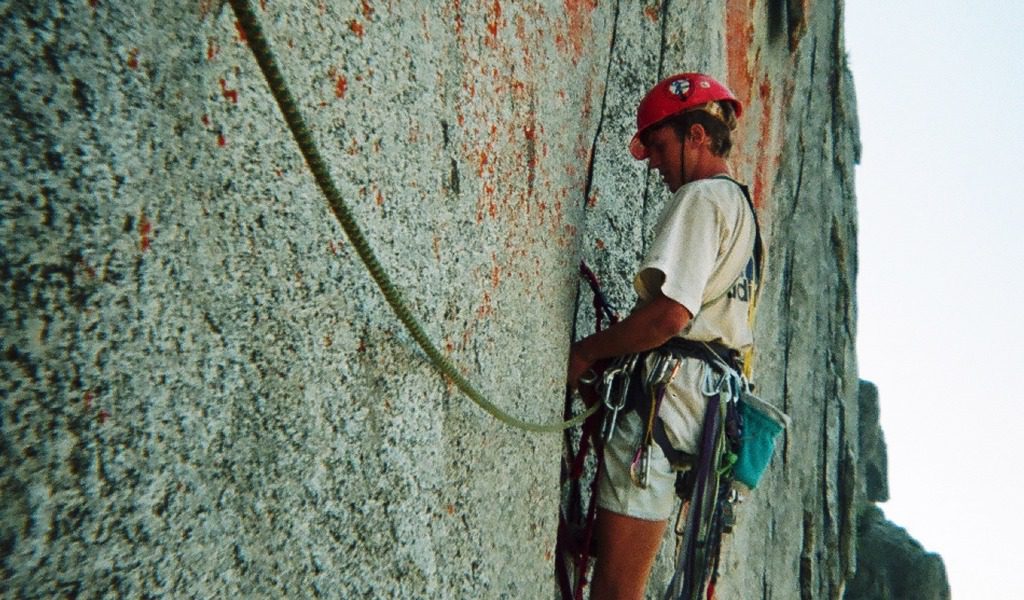

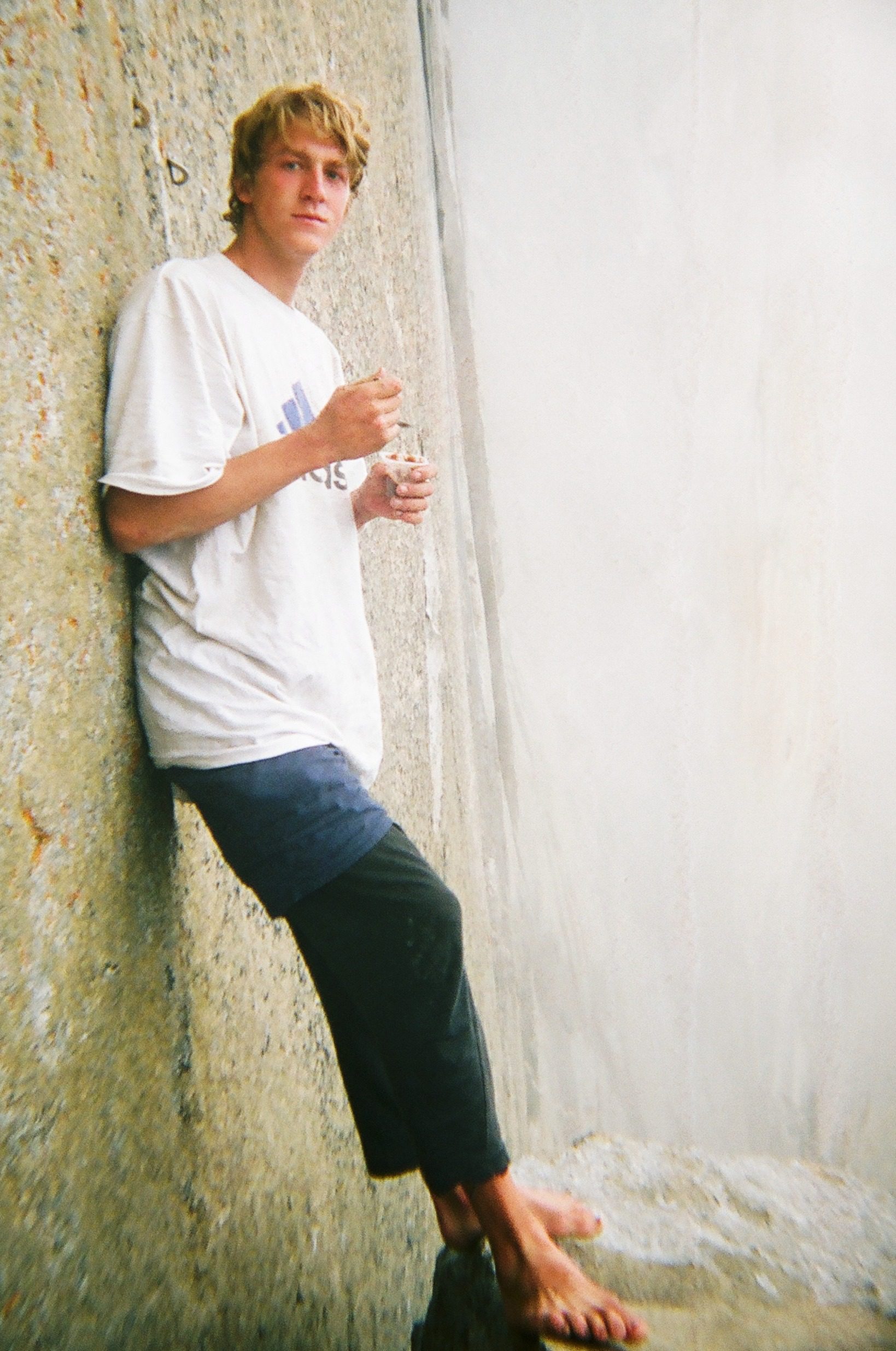

Photo by: Jason "Singer" Smith

Photo by: Jason "Singer" Smith

“I hardly ever took rest days; I didn’t need to. I was young,” Ben tells me from across my home office during a snowy day in the Sierra foothills of Mariposa. During his first visit three days ago, he arrived in shorts, a tee shirt, and bare feet, even though it was a cool winter day. This is the Ben I knew, I thought, always without shoes. But today it’s snowing so he’s dressed in the wool sweater his daughter, Antigone, 18, made for his recent travels in the Arctic. I haven’t seen him in decades before today. We’re catching up as old friends. He’s sharing his story with me and telling me about his business Zartman Rigging, which makes titanium prototypes of belay devices.

The past season, he had the “most epic sailing experience of my life,” he tells me. “It was the hardest and most committing.” For 112 days, Ben joined big wall climbers, who, like him, cut their teeth in Yosemite, Renan Ozturk and Mark Synnott, sailed across the Northwest Passage. This 6,000 nautical mile crossing in Synnott’s 47-foot sailboat Polar Sun took the crew from Maine to Alaska.

Three months ago, in September, Ben returned home to his family in Rhode Island one day before his daughter Emily’s 16th birthday. Here in Little Compton’s fishing village, Ben, a licensed captain and rigging company owner, raises his family.

He lived in Yosemite in a cave from 1995 to 1999. And it was in the Park that he met his wife, Danielle, 22 years ago at Degnan’s Deli. “It was a Deli love story,” he tells me. From 2000 to 2003 they sailed a thrift store sailboat to South America. That year they moved to Mariposa, 1 hour west of Yosemite, where he built a boat that he sailed 12,000 miles in with his family. All five of them lived on 31-foot “Ganymede” for five years, once sailing from San Francisco to Newfoundland. That enormous journey took them through the Panama Canal and required four years.

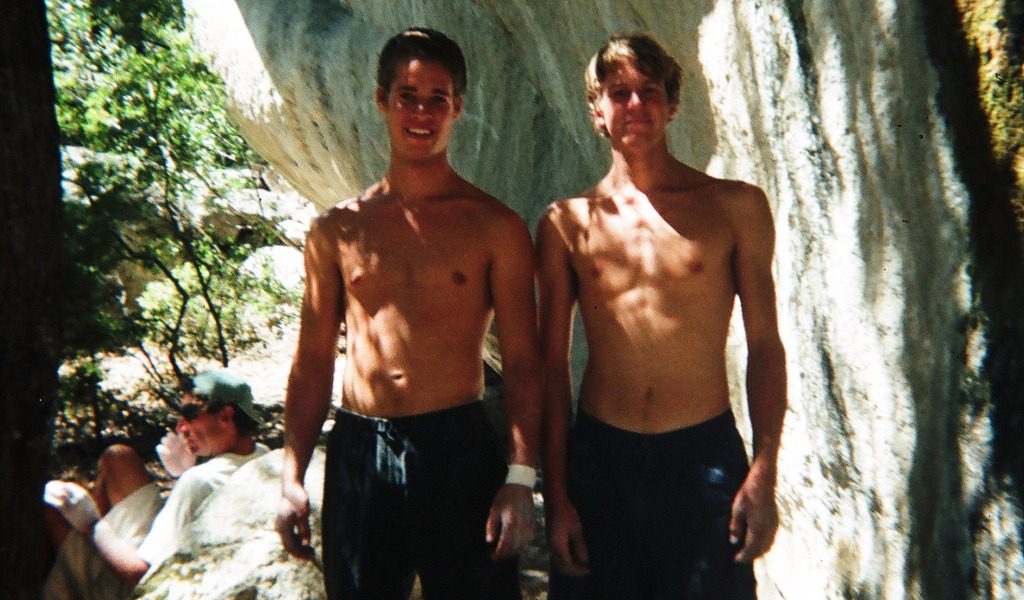

I met Ben during his first season in the Park when we were both 18 and we climbed our first big wall together, the Regular Northwest Face of Half Dome. I was so dehydrated on Half Dome that I hallucinated toward the top and saw a tiny fisherman. Two years later, we climbed El Cap via the Pacific Ocean Wall. For nine days we endured our way up the wall, where storms filled the Valley and rains permeated everything we had with us. These were epic, impactful climbs for us, at least for me. One night on the PO Wall a vicious storm thrashed our portaledge so violently we feared it would buckle and leave us stranded and hanging from the wall.

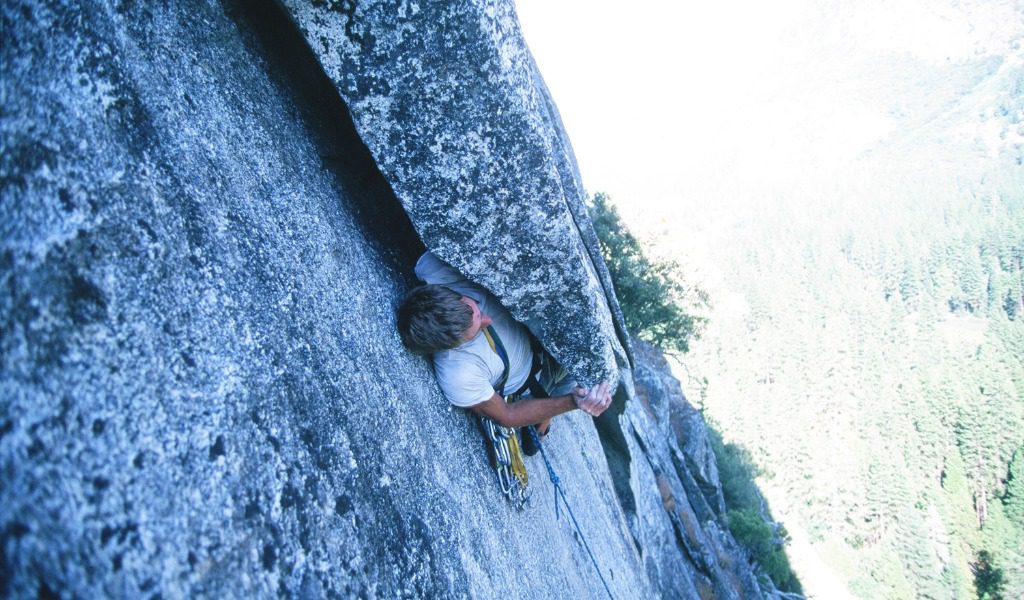

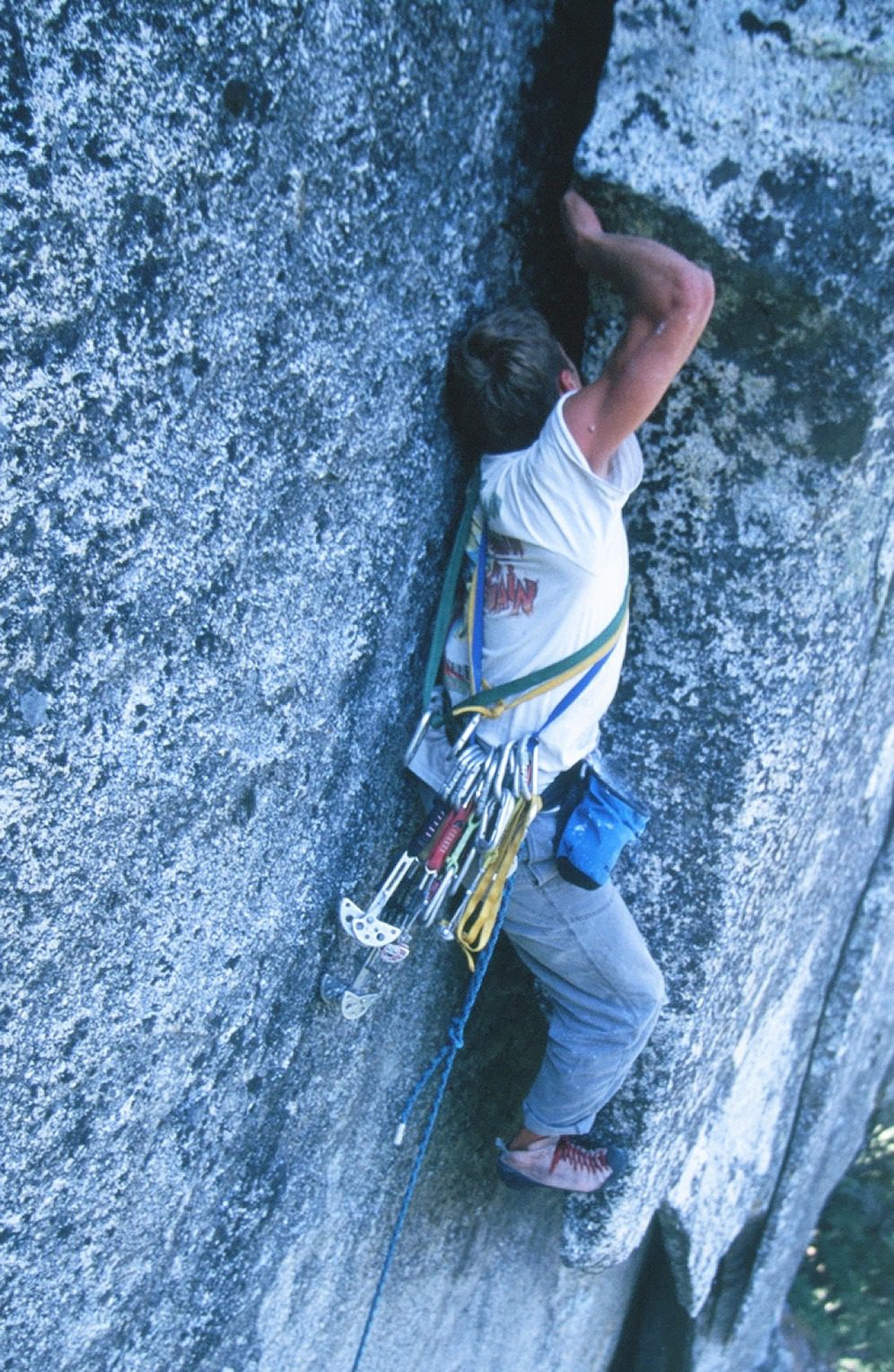

In addition to seeking adventures of the highest caliber, Ben and I shared an affinity for historic climbing gear. We often climbed with hexes and stoppers instead of cams, and we both climbed in swamis – Ben still does.

Back in the nineties, we climbed around my work schedule but Ben didn’t have one since he slept in the boulders above Camp 4 and lived off cafeteria scarfing and can collecting. One season he worked on the night crew with a local cleaning service.

Scenes remain in my memory from those times. Like when he dug up a jean hat he had hand-sewed and buried in the boulders before leaving to boat hitch hike to Mexico and the Caribbean. He unearthed it right before we did the East Buttress of Middle. I remember thinking, “you’re not going to wear that are you?” He whacked the hat against his thigh a few times and didn’t bother removing the excess dirt; he just put it on. For years I didn’t see him take it off. “There’s a picture of me soloing Zodiac (on El Cap) with that hat on somewhere,” he says.

Born in Uruguay to missionary parents, Ben is the second oldest of four kids. Due to his parents’ work in the church, the family relocated every few years. From Uruguay, they went to Colombia and Mexico. “My parents are still in Mexico,” he says, “they have not moved on from there.” Ben picked up climbing at 14. Someone he knew invited him to Copilco in Mexico City, and after his first visit, he regularly returned by himself to climb with whoever was there. He bought homemade, used climbing shoes and borrowed EBs – “they were horrible” – and wore a homemade harness and used knotted slings. He also used homemade cams made with plastic triggers and tennis racket strings. (We used those same cams on Half Dome, along with drilled-out hexes, Tricams and RPs.)

When Ben wasn’t climbing at the crags, he was hooking up a spiral staircase and jumaring up the side of his house. Like me, he moved to Yosemite straight out of high school. We met in Curry Village when our mutual friend Greg introduced us and convinced us to join him on Half Dome. “It was Greg’s mad scheme,” Ben recalls. “I was a gumby,” he says.

Ben arrived in Yosemite by bus in summer 1995 after traveling by Greyhound from Ohio. From day one, he bivied in Camp 4 until his friends showed him how to reside in the boulders. That November, Ben hitchhiked to Joshua Tree and lived in a cave until a government shutdown forced him to leave. From there he hitchhiked and bussed to San Diego and walked around the docks for days looking for a boat heading south that needed crew. “I didn’t know you could boat hitchhike, I just hoped that you could do it,” he says. The first boat he caught was called Spirit Bird, a 44-foot Ketch, where he joined a family. They needed watchstanders, which Ben was willing to do so long as it meant a ride to Mexico. “It was my scheme to come home to my parents without having to buy a plane ticket.”

This became Ben’s rough routine – climb in Yosemite for eight months, sail to Mexico for four. Over this period, he ticked nine El Cap routes, including soloing Zodiac and Dihedral Wall. Others include the Son of Heart (A4) and Atlantic Ocean Wall (A4). His specialty was the wide, and in 1998 he established a 5.11c Viva Gorditas on Lower Brother. He climbed the Bombay chimney with two wide cams, a 6 and 7, a swami belt and high top Asolo Dolomites climbing shoes. He also free soloed the Steck Salathe route on Sentinel rock, a 1,600 foot 5.9 filled with squeeze chimneys. The climb took him five and a half hours from car to car. He also soloed Bad Ass Mamma, 5.11d, located on the horse trail near the Ahwahnee Hotel, which he calls a highball instead of a solo even though it’s not in the local bouldering guide. The route required him to invert twice, and from there “you just grovel.”

During his dirt bagging years, Ben lived off peanut butter and tortillas, honey packets from the Deli, Ramen and discarded food that he scarfed off discarded plates, usually hash browns, pancakes soaked in syrup and toast. One day at the Lodge Cafeteria, and dressed in his customary thrift store clothes and as dozens of dirtbags watched, he rode the conveyer belt from the dining area into the kitchen. “When I got there, I asked where the bathroom was,” he says, adding “that was my proudest first ascent ever.”

To this very day, Ben doesn’t eat vegetables, convinced they are too low on the food chain for his taste.

In 1999 Ben left cave life to sail around the world, but the owner of the boat never motivated to go, so instead, he and Danielle bought a sailboat at a thrift store in Coco Beach, Florida, and sailed it to Colombia. From there they sailed to Maine but en route, they found out they were pregnant, so they returned to shore, came to Mariposa, and spent the next six years building a bigger boat.

‘When the boat got too small, or the kids got too big,” they moved to Rhode Island, where he became a captain, bought a house and settled down. When his three kids –Damaris, Emily, and Antigone—became teens, Ben began taking them on climbs. It was then he also began adapting sailing technology into climbing. “A few years ago, I started making things stronger, faster, lighter,” he says. This includes using custom Dyneema rope that’s only a quarter inch thick, a micro Stitch Plate and custom runners that are not sewn or tied, and quickdraws that weigh a fraction of what is available on the market.

The hitch? By using non-corrosive titanium instead of aluminum and Dyneema instead of nylon, his designs are cost-prohibitive for manufacturers. An infinite loop sling costs $45 retail. A prussik loop costs $40. A custom quickdraw costs $45 for the softgoods alone. His three custom belay devices cost him $500 to have machined out of titanium. He prefers titanium for it’s lightweight and superior heat distribution. He prefers his slings “because they’re better,” he says.

Each sling is tested to 30 per cent, weighs one-third of what’s on the market, and has a similar breaking strength of over 5,000 pounds. The technology is scalable so he can make custom anchors for any requirement.

When Ben’s not tinkering in his garage, sailing with the family or captaining a ship, he’s found at Cathedral Ledge in New Hampshire with his family. Here they all climb with his designs. “I don’t have any runners that aren’t my design anymore.” He leads them up multi-pitch routes with hexes custom slung on Dyneema, consignment climbing shoes that he scores for cheap – they all have shoes from there – and his custom swami belt. He leads on a regular climbing rope but top ropes on his custom ultra skinny line since it’s static. As we chat at my house, Ben ruffles through his pack and shows me his knotless swami, a design he perfected to climb offwidths and clip in with when sailing.

Then Ben looks over at me and tells me about meeting with the rope manufacturer Sterling just before setting off for the northwest passage. “I had them spellbound for four hours,” he says, as he told them about his life and climbing. “But then they condemned me for climbing on a rope that’s 12 years old.” They said they couldn’t work with Ben’s ideas because the production costs were too much.

What’s next for Ben? “I hope to combine my love of sailing and climbing big walls with a trip to Baffin Island. I also hope to partner with companies to see my gear produced.”

“It’s no question that I’m a little out of shape. Of course I want to do Astroman again, but I’ll never do that. I’m kinda old for becoming a climber again,” he says while pinching his midsection through his wool sweater.

“I’m not going to solo a big wall out of the boat, but I can still jug lines and be part of a team; I just won’t lead A5. But I can still climb with my family and organize sailing logistics for a climbing expedition to Greenland. I can also rig slacklines – imagine a sailing, big wall slacklining expedition to the Arctic.”