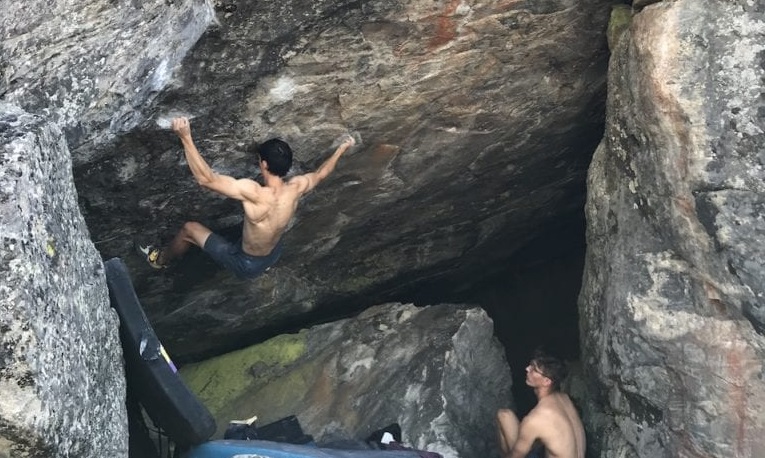

Canada’s Newest World-Class Bouldering Area

We spoke to Okanagan Bouldering guidebook creator Andy White on Canada's newest world-class bouldering destination in B.C.

It’s big. Perhaps that is what is lost in communication between the east and west coasters seeking to suss out the Valley splitting the southeastern side of British Columbia. If you have made the drive, you probably fired through the area in a matter of hours.

Certainly it’s beautiful, but how much bouldering is there really in the Okanagan?

Meet Andy White. With a guidebook boasting over 1800 boulder problems from over 200 kilometres of world class rock climbing, it’s shocking how little attention has been drawn to the area. This last summer saw a significant uptick in the number of climbers making their way out to the Okanagan Valley. Why had they not made it out before? Why are they coming now?

According to White, “When you grow up on the coast near Squamish you think that it can’t get much better, that it’s the place to be. Honestly, I didn’t really think there was that much bouldering around here when I first moved out, but I wasn’t that ingrained in the community. At that time, there wasn’t much of a bouldering community in the Okanagan. Sport climbing had always dominated the scene, the bouldering is amazing though.”

“The quality and the difficulty of the style is incredible, it’s what I love. I love Squamish bouldering as well, but it doesn’t quite get me like the bouldering here.”

White grew up climbing in Squamish with a focus on trad before an accident directed his attentions toward bouldering. Before the accident he had moved out to the Okanagan having just finished university and, with big falls behind him, looked for other ways to enjoy B.C.’s beautiful climbing.

“In the south Okanagan, a lot of the obvious bouldering had been developed before we came on the scene. There were people developing the Kelowna Boulderfields before we got there. Chris Reeves who owns Gneiss was in there with Mike Shannon who used to own Beyond the Crux in Kelowna. Other local developers had been in there for a number of years before we got there, but the concentration, the exploration, wasn’t there.”

“It just wasn’t on a scale that we brought to it later on. When I say ‘we,’ the original big push was only a handful of people. However, that handful of people put up hundreds and hundreds of problems.”

“We probably started developing just over 10 years ago, and we were fairly new at it. We were developing a lot, quantity over quality at the start, and nothing that difficult because we weren’t climbing at that difficulty yet. Then, as time went on, we explored a lot more of the areas. We started focusing more on quality and difficulty.”

“There was little bit of bouldering included in an older sport climbing guidebook written by Karin and Yanni, but it only included 30 or 40 problems in it. It wasn’t long, maybe a season or two in, that we had gone up to 400-500 problems in the Boulderfields. This was around the time that we began to think that this place was pretty good and that it could be cool to get the information out. We put out a small paper guide that had 400-something problems in it just to carry people over in 2012.”

“Quite a while later, I decided I should actually put a proper published and printed guidebook out for the area. That was the book I put out in 2018.”

This 1800 problem rich book considered the combined effort of many years of several developers each working toward building up the area. Whit waited to publish late into development out of consideration for the area, spending time building the Okanagan Bouldering Society to cover access issues, develop campgrounds, and work in conjunction with land managers, local governments and related bodies. This preliminary work, though challenging, paved the way for what is slowly becoming one of Canada’s premier bouldering destinations. Have they finished developing? Not even close.

According to White, “We are still plucking amazing projects out. Every year I think that my project list is going to get down to almost nothing, and then by the time that the end of the season comes, it has doubled instead. I love it. That is probably the best thing that could happen for someone that is trying to climb all of the time.”

“There is this area to the far-east section of the Boulderfields that has some of the best problems in Canada, it’s just a little bit more adventurous and a little bit further to walk. The blocks are big and wild, and there is still so much more to be done in this spot. In the northern part of the Fields, where Where’s Wildo is located, that area has had a number of us excited these last couple years. There are still probably 20 or 30 problems that are top quality lines at lower grades and they haven’t been scrubbed yet.”

“If someone wanted to go out there and spend a lot of time, they could have an entire career finding other stuff I’m sure. If you like higher, more committing stuff, oh man, we have bolted boulders that are the size of apartment buildings.”

It should be mentioned that most of the above is related specifically to the easily accessed Kelowna Boulderfields, just a single section of the 200 kilometres of development that span the Valley north of Penticton. So what has held people back from coming? Well, it’s kind of hidden in the shadow of the Chief. Climbing media tends to play on that which has long been popular. It’s a profitable self-perpetuating system that overlooks absolute gems like those resting in the valley.

The quality of the climbing is difficult to overstate within a Canadian context as the area offers a significant portion of Canada’s best, and most difficult boulder problems. What is most surprising is how this system has perpetuated when the Okanagan offers one of the longest bouldering seasons in the country. Spanning from mid-February through to November or December, depending on the year, the Okanagan even offers a small winter training season to allow for a complete year-long cycle.

Though some might think the desert-adjacent area becomes too hot in the summer to boulder, the severe overhangs and high elevation mean than some problems never warm past 15-20 degrees Celsius.

These misconceptions, in addition to the general subtlety of the local crew has led to the near-secret, in terms of a global context, development of one of North America’s largest bouldering areas. With potential in abundance, the final questions that arise about the area are regarding its detail. What is it like to climb in the Okanagan Valley?

White said, “For the most part, it’s gneiss and it’s hold ridden. You get a lot of different types of holds. Slopers do exist here, but on a lot of our harder stuff you have to be able to climb on the steep, and typically on edges. The edges here don’t typically get a lot of in-cut on them.”

“You find that you have to learn to climb with a lot of body tension, finger strength and power. A lot of us took years to develop that, and now we specifically train it. You can’t jump around like on a MoonBoard or in a comp,” instead, you have to keep your feet low, and move with intent, latching holds and bearing down in the crease of the feature.

He continued, “I think it relates really well to the Hueco style. You just can’t cut your feet as much because you can’t get behind the holds.” The powerful style has allowed for some heinous first ascents of some of the country’s hardest including Slippery When Wet, a V13 with a possible V14 low start. Where’s Wildo is another V14 out in the Fields and, White’s personal favourite, the notorious No More Mr. Gneiss Guy.

Though originally put up at V12, back when the local developers did not believe that they could climb much harder than 8A+, recent visits from touring climbers have nudged the difficulty of this and many other climbs toward the upper echelons of difficulty. Now rated somewhere in the V13/14 area, the unrepeated classic is definitive of the area’s style.

White would say, “In 2015, at the beginning of that season, Aaron Culver was out that way and he found No More Mr. Gneiss Guy. He and Jay Duris, who is probably the godfather of development in that area, said, ‘You gotta go try this thing, it’s perfect for you.’”

“Finally, I decided that I would go with them. You walk through a bit of tallis and you get to this boulder. You walk around the corner of the boulder and you see the perfect 55- or 60-degree angle. The holds are laser cut on the wall. It’s like perfection in a boulder problem. I was struck immediately and got on it that day.”

“The first sequence of moves is hard, but not that hard, so I did those that day. The last sequence of moves is also hard, but not that hard, so I did those that day as well. The crux, however, is difficult. I spent the next four-plus months working that one move, being really stubborn and learning that, maybe I could climb something that hard if I put that amount of time and energy into it.”

“After working it that long, the temperatures dropped at the end of August and it happened to all come together. The left foot has to stay. If the left foot comes off, you’re hooped.”

“I started with a left foot on with a hard-right back-flag, before going up right hand. Then, my left foot is already on this low hold to just step up to grab the diagonal. Then, all I needed to do was switch feet and step the left foot really high. When you do the huge chuck move, your right foot is on a really good foothold and your left foot is super high, kind of jammed up almost, it wants to push you off the wall.”

“You need to learn how the body works to get your right foot to push up so that you can get high enough to start engaging your left foot. Then your right foot comes off the wall and you chuck, and your left foot has to stay on the wall while your left hand holds this terrible diagonal rail, and your right hand catches a beautiful good edge: totally horizontal. It’s a very complex movement for it being one freaking move.”

With one of the hardest single moves in Canada, trying this problem has become a rite of passage for those looking to test their mettle in the Fields. Though exceedingly difficult, this problem is but one of the many classics that define Kelowna, with difficulties ranging the full span of possibilities.

Toward the lower end, “The Butterscotch Ripple boulder is probably one of the best in the Fields. It’s strangely foot-technical, on slopey pinches, almost tufa like, with an arete.” To that effect, “Dangle Berries in the Dominator Roof,” is an exceptional V6. White continued, “V6 is actually a really good grade in the Okanagan. So many good lines, but that one is really cool because it’s so steep with in-cut holds. You can really swing around on them.”

As difficulty increases, “Baby Cthulhu is a steep prow with these water-worn wavy features. Very steep, technical, toe-hook heel-hook tension moves to a lip. People say it’s one of the best of the grade in the country,” though that grade is disputed between V7 and V8.

At the upper end, before hitting the V13+ boulder problems sit two area classics. “Nerf Roof, V12ish, is one of the most iconic features in the country, while Crouching Dragon hidden Tiger in Cougar Canyon is an incredibly steep prow. People that climb it say that it’s the best boulder problem of whatever grade that it’s in the country.”

Amid this slew of boulder problems, resides an annual outdoor climbing competition called the Rock the Blocs festival. Built out of an idea to increase the area’s popularity, the annually growing competition features some of Canada’s strongest outdoor climbers, roaring on many of the country’s best boulder problems.

“It’s pretty much a Canadian Rock Rodeo, and the atmosphere is so cool. You get all of these people here all of a sudden and it’s a competition, but you wouldn’t necessarily know it because everyone is so positive about what is going on. You have all locals running it, it’s a really cool vibe, it’s a tonne of work, but it’s well worth it. You get to see people in the climbing community that you wouldn’t otherwise see some years.”

This positive vibe is perhaps the most distinguishing characteristic of the Okanagan Bouldering Crew. Through modesty, respect for their land, and community support, the Okanagan Valley has turned into one of the most accessible, and radical areas in the country to go boulder.

For those looking to make their first trip out to the area, the Kelowna Boulderfields are a great place to start, with superior campsites, picnic tables, fire pits and a restroom. Be sure to bring your own water and do not be afraid to hit up the locals for a little advice. The welcoming atmosphere of the Okanagan, the superior boulder problems, and the radical climbing experience each build to produce a world class bouldering area.