Dealing with Life and Death in Canada’s Mountains

A rescue technician and a psychologist from the heartland of Canadian alpinism, on death, life and why climbing is worth it

A media panel at the Kendal Mountain Festival in the UK in 2020 were asked when they first heard of the death of climbers Jess Roskelley, David Lama and Hansjörg Auer on Howse Peak in the Canadian Rockies in November, 2019. Gripped’s editor, Brandon Pullan, like many climbers in Canmore, had started hearing rumours about the overdue climbers before anyone knew what had happened. We later found out that the tragedy on one of the most extreme faces in the Canadian Rockies had claimed the lives of all three climbers. The aftershocks and analysis of what happened continue, not just among the loved ones of the victims, but in the global climbing community.

On a sunny day at a roadside crag in the Rockies, my partner and I came across a rope tied to an anchor of a popular climb and apparently left behind. We wondered why anyone could have left it there. Later that day we found out that there had been a fatal accident caused by a simple climber’s error many of us have made. The rope was left behind during the rescue effort.

Whether we accept it or not, we all choose to take serious risks when we climb. Intelligent choices, modern gear and technique and much better information about conditions and weather make death a more remote possibility, but it’s still a possibility.

A climbing accident is, by its nature, unexpected. In the duration of the incident, the climbers and then rescue responders are physically at risk. In the months and years that follow, everyone involved, including the survivors’ and rescuers’ loved ones remain vulnerable to psychological and emotional effects of the accident. Although I have climbed for four decades, I have a limited direct experience of tragedy in climbing and have never been in a serious accident. And yet, I still regularly think about four climbers I knew who disappeared on Denali in 1980, when I was just 18. It’s a sad feeling of lost potential that in some ways inspired me to befriend or research climbers who courted risk more openly than I did, as mostly a rock climber.

In a brief conversation with Reinhold Messner at the Banff Mountain film festival, I was struck by his statement that “deaths are good for climbing.” Of course, he didn’t mean anyone should be killed or make decisions that knowingly led to their deaths, but that the seriousness of the pursuit is integral to its nobility. I was intrigued enough to want to write about what risk still means in climbing, not just for elite athletes, but for everyone. I decided to talk referred to two climbers with much more direct experience and reason to think about the matter than most.

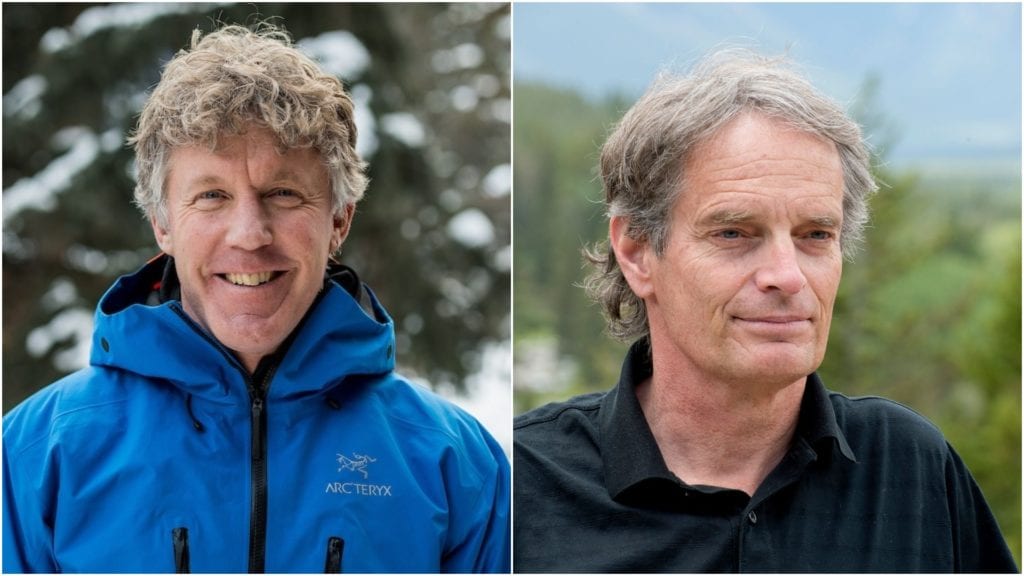

Grant Statham was a top alpinist and ice climber in the 90s and 2000s, and is now a rescue technician for Banff, Yoho and Kootenay National Parks. Geoff Powter is an author, a skilled climber in a variety of disciplines with more than four decades of experience and a psychologist. Both live in Canmore, a community at the heart of the Canadian alpine community.

Statham and his colleagues have been called out to so many different rescue situations that they are reticent to judge anyone who has bad luck in the mountains. On one call, Statham and his team-mates rescued a man who had wandered off in January in what he calls, “an altered state, and found himself way up on the side of a mountain in the night with no clue where he was or how he’d gotten there. We climbed up to him through the night, warmed him up and then lowered him down through some cliffs. We brought him soup and a sleeping bag and bivvied with him on a ledge, then the next day we picked him off with the helicopter.” Statham surprised me with his regret that he never heard from the man again, not because he was looking for gratitude, but because his view of rescue and recovery extends to the aftermath of an incident. He wanted to know if the man was all right.

In the eighties and nineties, Statham became a major player in the hard alpine scene in the Canadian Rockies and beyond. He made the second ascent of Wild Thing on east face of Mount Chephren, the first ascent of Astrofloyd on the east face of MacArthur Peak in Yukon, and climbed the Scottish Pillar on Bhagirathi 3 in the Garhwal Himalaya in India. His aggressive leading occasionally led to significant peels that won him the nickname Whipper.

And yet Statham is soft-spoken and disinclined to bravado. At just 24, he became a full ACMG mountain guide. He also discovered that accidents brought out both a talent for making rapid decisions and a desire to help people in trouble in the mountains. In the first few weeks of his job as a ski patroller at Sunshine resort in 1987, a ski lift derailed and he helped with the first aid and evacuation of seriously injured skiers. Statham realized that, in his words, “attending an accident is different than being in one. I think everyone [who helps out in an accident] has different motivations, but I realized that the intensity was a little bit like leading a hard pitch and that I like helping people; providing comfort and helping them out in the most terrifying moment of their life.”

After that incident, legendary climber and rescue technician Tim Auger suggested to Statham that he might be cut out for work as a rescue technician in Canada’s national mountain parks. Statham continued to expand his professional knowledge as an avalanche forecaster (he is now an Adjunct Professor, Simon Fraser University, Avalanche Risk Management) and a heli-ski and climbing guide, and in 2003, he was hired by Parks Canada to overhaul their public avalanche safety systems.

Now he’s part of a team of nine rescuers and one dog master who work in Banff, Kootenay and Yoho national Parks. It’s a busy job, with 350 calls for help in a typical year. In many cases, the rescuers can help without going in to evacuate. “It’s a badge of honour,” says Statham, “to talk people down, people who are just freaked out and need some calm advice or directions. A lot of times, people call and we talk to them through night, maybe park at the base and put on our headlights so they can see us.”

But if anyone is injured or unable to extract themselves safely, as is the case in some 175 calls a year, they go in, either by foot or helicopter. Of these calls, the Banff National park classifies some 25 instances as “technical mountain rescues,” or the kind of nightmare situations climbers and skiers dread.

In these situations, there is no replacement for the teamwork and technical excellence of both the pilots and the team members. Some of these rescues are extreme, to say the least. “There was a guy skiing who fell down a couloir,” says Statham, “He had a serious head injury, the weather was poor, there was hard flying and overhead hazards. We got him, he spent a month in hospital and I never met this guy since. Those are the things you remember.”

And yet, Statham says that mishaps resulting from simply “being prepared but having a bad day,” are more frequent. “Rockfall accidents are common,” says Statham, “both natural and climber-caused. Climber error, something done something wrong at belay.” Easy, popular routes have the most accidents. “Mount Temple and Rundle are hotspots,” partly because of their easy accessibility.

Statham is slow to judge the victims of climbing accidents, but he has accrued some insight into what can avert problems: “Leave someone a detailed plan; where your car is parked; lots of calls are from the family members of overdue people whose location is unknown. Carry a communication device. Be searchable and, if you’re in avalanche country, even if you’re ice climbing, use an avalanche transceiver. People think that if they get hit by an avalanche while they’re ice climbing they’re going to get killed anyway. Statistics don’t support that. Mostly climbers hit killed by avalanches die of asphyxia [they’re buried], not trauma from the fall. The statistics [from non-climbing avalanche events] support the notion that there is significant potential to be recovered alive if climbers wear transceivers.”

Statham has advice for those who don’t use an avalanche transceiver and insist that the rescue team “just leave them out there.” “We put tremendous resources into bringing closure for family members,” he says, with some understatement, meaning body recovery, in the rare instances of fatalities. There is, or should be, something a little chilling about contemplating what might happen to your own corpse and the fact that your loved ones will want it back.

Rescuers are first-responders and the emotional side of thinking this way and dealing with so much stress and occasional tragedy has to be taken very seriously. “On the rescue itself, we go clinical,” says Statham. “It’s an operation, we’re on point, not moved by emotion. It’s game-on, like leading a hard pitch.” Myriad variables affect the emotional cost of a given rescue. “It’s easier if there is less of a time restraint, [i.e., no serious injury that needs immediate attention or, let’s face it, death] If it’s someone you know, or you have some personal connection to the incident, it can be so much harder.”

“Afterwards it can be draining,” says Statham, “and the stress can last for months.” The team uses a protocol called Critical Incident Stress management to prepare and de-brief from rescues. They have regular baseline psychological training and training with the “Working mind first responders” program. “We learn to recognize when the others are struggling. We have our own personal programs, a formalized debrief right after events, and look at things from an emotional standpoint.”

The emotional component of recovery extends to the victims’ loved ones. “We do a tremendous amount of follow up with families. We explain what happened to people who might not understand. Sometimes we take them there, explain what happened, help them close the situation. It can be tough, but it’s the most rewarding part of job, where I can help a loved one get closure.”

Statham’s views on the meaning of accidents and the value of risk continue to evolve. “People should be able to climb what they want,” he says, but clearly, he has some provisos. “When I was younger, I was always going for it. Risk was part of it, I embraced it and didn’t think past it. Now, I go to all these accidents and they don’t affect me individually, but collectively I think they add up. Now I see these family members of victims and I question so many things I believed in about what I love and its cost.”

When Roskelley, David Lama and Hansjörg Auer died, Statham was part of the recovery team. Looking out the helicopter window at the face of Howse Peak where the accident had happened, he was filled with memories and emotions. “It was a harder recovery because I knew the long history of that mountain and had climbed it. My friends had also climbed it and we all knew the ice routes up there, having stared at them and dreamed about them for years. The whole experience was very reflective and felt close to home. I have to think of that accident as two stories. The climb was incredible, one of the greatest bits of climbing ever, and on the descent, it became one of the most tragic. Five minutes either way might have saved them. But I had to admit to myself that if I was younger, it’s what I’d want to do. And then, couldn’t help asking myself why.

“I spent a lot of time asking my friends and our community about the incident, looking out helicopter windows, flying around. It was the first time we used geotags on photographs from a victim’s phone to pull location tags determine their location and basically find out where they went. Then Jess’s father, John Roskelley, made three trips to the area and found gear and a camera and we put together the timeline of what happened.

“The first year after a fatal accident can be the hardest for people. There’s a desire to know about what the person did, right or wrong. The biggest responsibility for us is to be honest and say what we think happened. What could have different? There are often two stories: the truth and what becomes public. I try hard to stay out of the public story.

“Rescuers don’t pretend to have all of the answers to what happens. In some ways, [rescue work] has made my mountain experience richer. The memories and thoughts about what we do are always there. My mind drifts to that stuff all of the time; it can be tripped up by a moment of stress or difficult decision making, of five minutes trying to decide exactly what to do.”

Geoff Powter started climbing in the east in the ‘70s and saw a climbing fatality in his first month on the rocks. Then he had a bad fall. But he kept at it because, in his own words, “it was worth it.” He proved his faith in that simple equation in a four-decade career of alpinism, big wall climbing, hard free climbing, soloing and expeditions.

Powter has become a leading climbing and adventure author who has explored the difficult issues of death and the psychology of climbing in his book, Strange and Dangerous Dreams, (2006) and numerous live interviews with leading climbers at the Banff Mountain Film and Book Festival. His 2019 collection of essays, Inner Ranges, includes “27 Funerals and a Wedding,” one of the most eloquent pieces ever written on risk, death and climbing, the differences and the overlap of regular life and climbing tragedy.

After a year in which his own mother died as well as climbers he knew and admired, Powter comments that “Blood was back on the surface of things -of everything it seemed – and I was given the chance to question the differences in all these losses.” It is also the only essay on climbing I have read which contains a necrology – a list of the climbing dead from his life, which is long enough, despite my sense that it isn’t complete.

Climbing, for Powter, is noble, but far from simple. “I’ve watched so many of my friends get so complicated after these climbs,” he wrote of Himalayan alpinism, “with sadness and emptiness suddenly a part of their lives because it seems nothing will ever match the summit.”

Powter came by his insights over a long, close, insider’s observation of the game. He moved to Alberta from Montreal in 1979 to study psychology and immerse himself in the climbing scene. Becoming a “psychologist was completely separate,” he says, “I was fascinated by what makes people tick and I found the risk-taking aspect of climbing to be one of the most interesting manifestations of that.”

He became a close friend and climbing partner of Dave Cheesmond, an alpinist of international stature and a South African emigrant to Canada who had helped Black climber Ed February fight for the rights of black South African climbers. Together, Cheesmond, Urs Kallen and Powter worked to establish Polar Circus, Canada’s first climbing magazine Cheesmond’s disappearance on the difficult and still unrepeated Hummingbird Ridge on Mount Logan in 1987, with his climbing partner, American Catherine Freer, shocked the Alberta alpine scene, which was already used to losing their own to climbing. Cheesmond’s technical excellence and experience had made it seem like if anyone would survive, it would be him.

“There had been death after death,” says Powter. “It was pretty remarkable, I think there had been a couple dozen since I had arrived from the East, but David’s memorial stands out in my memory. The service itself was sombre, serious, then at the wake there was this huge release. Some people got really hammered, and we danced maniacally.”

The almost ritualistic release of tension, the acceptance of what had happened as part of the story of climbing; as part, in Powter’s words, of “playing the game hard,” had an authenticity to it. To accept that death is part of climbing, says Powter, “made the game more serious and honourable in a Bushido kind of way,” referring to the Japanese warrior’s code. “Having been born into the house of a warrior,” said the Samurai philosopher Katō, “one’s intentions should be to grasp the long and the short swords and to die.”

Powter’s CV includes dangerous lightweight Himalayan climbing and free-solos like the 300 metre 5.11a CMC Wall on Yamnuska, which is still an aspirational roped route for most climbers, and so he’s got first-hand experience of the mental twists that are required to accept that warrior’s code. At the heart of it, though, is his insistence that you have to be crystal clear about your intentions, and about all the possible consequences of your decisions: “Don’t sort your shit out,” he says, “playing this climbing game. All of us should have the choice to take the risks we want to take, but only if they have no immediate effect on others.”

During his decades as a climber, a mountain author, a friend to grieving climbers and a counselor, Powter has gained some hard-to-come-by wisdom. “Everybody touched by risk-taking — even by death — came out richer, even if they decided they didn’t want to do this any more, even if they were angry at a spouse who died; even if they were left in terrible pain at first. Everybody learned something. There were sometimes terrible consequences, but people learned. Maybe it’s a stretch, but I think that risk-taking, and its rewards and its consequences, have the power that they do because they are incredibly real, and our culture suffers from a lack of reality. When death isn’t a part of our life, we live a less authentic life. What’s more authentic than a life of clarity about truth and consequences? What’s more affirming than the consciousness that what I do every day in life matters?”

Powter’s ideas have evolved over time, but he thinks that the evolution in the climbing scene towards better technique, equipment and training hasn’t been entirely or solely positive. Perhaps this is what Messner was talking about: that eliminating risk includes the unintended risk of creating a less authentic experience. One shift that Powter has noticed is that it seems as though it’s no longer acceptable to have fatalities in our mountain games. While he accepts that this is, of course, in so many ways a very good thing, it’s also resulted in a pattern of much greater judgement of people when tragedies do happen.

“It seems sometimes like people are truly, genuinely surprised [when there is an accident], as though accidents just shouldn’t be happening, and that there is fault when they do.” Back in the 80s, he suggests, a greater frequency of consequential accidents clarified what the rules of the game truly are.” And this, he thinks, was “a good reality that served us all, and kept us from pointing fingers.” It also, he insists, helped climbers keep their eyes of the nobility of the warrior’s way. “We climb, we fail, we are not gods, but that doesn’t diminish the nobility of the pursuit. Never say it wasn’t worth it.”

David Smart is the editorial director at Gripped Publishing. His work has been shortlisted for the Boardman Tasker Prize and the Banff Mountain Book Festival. He is the 2019 recipient of the Banff Mountain Film and Book Festival’s Summit of Excellence Award. This story appears in the October/November 2020 issue of Gripped magazine.