Dreamcatchers, Nationals and Reconnecting Through Climbing

Kristen Blakney was commissioned by the CEC to make dreamcatchers for podium finishers. She hopes her story will encourage others to engage their Indigenous communities through climbing.

Photo by: Nic Nolet

Photo by: Nic Nolet

“I used to say that climbing was more than a sport, it was a lifestyle. I have since come to realize that it is even more than that, it’s a powerful connecter. It connected me to myself, and something that was really unexpected was how it connected me to my culture and spirituality.”

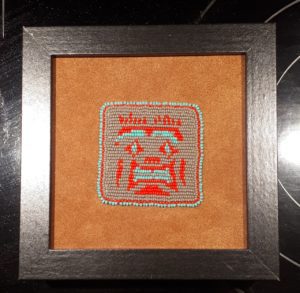

For those that follow competitive climbing in Canada, it may have come as a surprise. Alongside the more traditional medals and trophies, Canada’s Bouldering National Champions stood with dreamcatchers. Unlike more conventional builds, these looped and tied to a carabiner adorned with feathers.

The woman behind these dreamcatchers is Miꞌkmaq climber Kristen Blakney. Although Blakney may be an unfamiliar name to some, she has climbed in and around North America for the past 15 years. Blakney grew up in Minto, New Brunswick not far from Elsipogtog First Nation.

As a child, she spent time playing and bonding with her cousins and community. As she grew older, Blakney spent less time around her family, and put more time into sports and school. In University, she found herself only returning for larger family events.

“I kind of lost touch. I have a tough time accepting that because I feel like I missed out on a lot. I wasn’t there a lot, but at the same time, as I got older, I got to see some more troubled things in the community. Elsipogtog had a suicide crisis for a couple of years. It was a tough community and I saw that more as I got older. Some of the community I grew up with struggled with addictions and poverty.

“Part of it was that I didn’t go because I didn’t want to see that. Now, as an adult, I regret not visiting more as an older kid, as a teen. I regret not trying to know more about my family there. I was always angry at my mom for not teaching us the language, the Miꞌkmaq language, and not teaching us much about our culture. Not talking about it but I have come to learn recently that a lot of that is because my mom is an Indian day school survivor.

“A lot of my family went to the same school and there was a lot of abuse, a lot of trauma. This is why I believe that I grew up off reserve, why my mom wouldn’t let me live there and why I didn’t learn much about my culture..

“I didn’t know about my mom’s experience at the Indian day school until last summer. I’ve always felt not fully Native, because I’m not, I’m half. Now I identify with it, and I am proud of my culture, but growing up I wasn’t proud. I wasn’t trying to hide it, but I wasn’t trying to learn my customs and practice them.”

Upon entering the climbing space, Blakney began to reconnect. Being in nature and in these sacred places, Blakney found her culture and spirituality. “Something about living on the land really motivated me to start beading again and to start making dreamcatchers,” Blakney reflected. “Those were the two things from my culture that my mom taught me how to do. It reconnected me.”

This process of reconnection is one that Blakney and her sisters have voyaged down in these last years. Although she began to build carabiner dreamcatchers on the road, it would not be until Kamloops that they took on greater meaning.

“As soon as the news broke about the Kamloops Residential School and the unmarked graves, it hit hard. Nothing felt like that before. I knew that I needed to do something, that I wanted to do something more than wearing an orange shirt.”

Reaching out to a local climbing gym in Fredericton, Blakney organized an Indigenous climbing night. Fredericton Bouldering Co-op covered rental costs and day passes as local Indigenous climbers of all ages tried the sport for the first time. Blakney managed to secure prizes from the Radical Edge and food from a local Indigenous baker (Jenna’s Nut-Free Dessertery)the night was a success. 25 people showed up, and, as thanks, Blakney offered a carabiner dreamcatcher to memorialize the evening.

“This is a gift, a thank you for hosting this night,” Blakney said at the event. “I hope there’s more to come and I hope it also serves as a reminder for this night and the importance of connecting with our Indigenous communities.”

The gym posted a photo of the night and the CEC saw Blakney’s dreamcatcher. “They reached out to me and asked if I would make them for all of the podium winners. I agreed to do that, to donate all of the proceeds to an Indigenous fund. My dream is to create a fund to work with local gyms, where if you’re Indigenous and you want to try climbing, you can access that fund and come to the gym and get shoe rentals. I’m hoping to meet with a few gym owners in the next couple months to discuss that and see if it’s some sort of possibility.”

Already Blakney’s work has had an effect. She hosted an Indigenous climbing night at Bolder in Alberta. It is her hope to retain this momentum and build to support for Indigenous communities across Canada.

Featured image by Nic Nolet Photography. If you would like to order dreamcatchers or donate old carabiners or bike chain rings or sprockets to Blakney, message her over Instagram here.