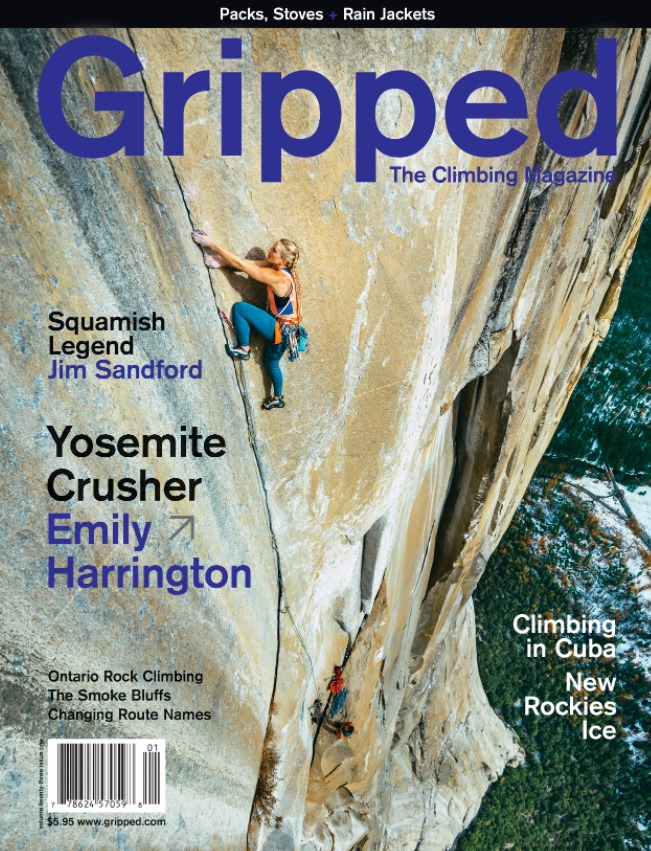

Emily Harrington Climbing a 41-Pitch 5.13 in Yosemite

Emily Harrington climbed Golden Gate in 2015 and 2020, and Louder Than Eleven just released a video of the former

Photo by: Jon Glassberg @louderthan11

Photo by: Jon Glassberg @louderthan11

Emily Harrington presses the tips of her toes onto the smooth granite flanks of El Capitan and stabs her right hand to a sloper. She pauses for just a moment to readjust her grip then stabs again, summoning all of her endurance for a powerful traverse almost a vertical kilometre into the sky. The staggering exposure does not register in her mind; she has never wanted something so deeply before. Harrington was about to become the fourth person and first woman to free climb Golden Gate VI 5.13-, 41 pitches, in a day and she had overcome far more than difficult climbing to get there.

Climbers will romanticize these images of Harrington on El Capitan. They will remember the look of confidence on her face while firing the A5 Traverse 5.13a and her dogged determination launching up the Monster Offwidth 5.11a. But Harrington’s ascent is more than a noteworthy tick. In 2012, Harrington, a national sport and mixed climbing champion, decided that being at the top of her field was no longer fulfilling. She wanted to be a beginner again; to feel completely out of her element. “I think as really good rock climbers we aren’t willing to step outside our speciality because it’s hard to not be good,” she explains. And so despite her long standing perch atop several climbing disciplines, Harrington stepped down and looked up; eyeing trad climbing, big walls and a world of uncertainty.

Harrington began trad climbing on California’s rough, crystalline granite. Her learning curve was scary, sharp and short-lived, as is often the case for champion competition climbers discovering the medium. But she was inspired by the do anything climbers, the ones who, upon finding any inspiring objective, could intuitively sense that they had the résumé to get it done. “It became important to understand all of the different climbing experiences,” she says. Harrington progressed quickly; learning the nuances between when to layback and when to fist jam, which 50-year-old Warren Harding bolts could withstand at least one more whipper and how ineffectual 5.14 fitness could be when faced with a 5.8 offwidth. But only three years after learning to trad climb, Harrington set her sights on a free ascent of El Capitan via Golden Gate — a lifetime achievement for any climber.

Harrington is refreshingly human while recounting her first brushes with exposure. She doesn’t pause to point out that she burst into tears the first seven times rappelling into El Capitan in 2015. She felt acutely vulnerable some 900 metres above the valley floor; mortified to take whippers and struggling to understand the root of her big wall impulses. Harrington spent many days refining her beta and learning to live on the wall that season. And while she went on to send Golden Gate in a six-day push that May, Harrington felt only a fleeting satisfaction. “I just barely sent that route,” she says. “It was scrappy.” Indeed, technical cruxes were punches she could brace for, but it was the miles of moderate terrain and an unassuming moderate offwidth, The Monster, which delivered many unanticipated blows. Harrington had found a space for herself on El Capitan but knew there was room for improvement. She didn’t dare voice that she thought a free-in-a-day attempt might be possible, but the six-day battle became a thorn in her side. She knew she could be prouder of a Golden Gate ascent.

The progression of whittling a six-day ascent down to one has many layers. Not only do you need the power and endurance to encounter 5.13 just a few pitches from the top, there is immense risk when climbing 900 metres of technical ground in a day. “There’s a lot of situations up there where, if you do fall, it’s not going to be ok,” she admits. Harrington refined her crack climbing skills in the years following her ascent and felt ready for a free-in-a-day attempt in November 2019. Unlike in 2015, Harrington says she felt quite comfortable up high; she could move quickly over moderate terrain and run it out with confidence. She chose to simul climb the lower portions of the wall including the Freeblast slabs 5.11, 10 pitches, with Alex Honnold and, on her first attempts, motored through the delicate climbing in only one and a half hours. As the 2019 season in Yosemite progressed, Harrington recognized that she had become more comfortable on the wall and was willing to take greater risks to ensure her success. “I became consumed with the idea that I wouldn’t succeed unless I cut all of the corners. And as with anything, you can take it a step too far.”

On her second attempt that season, Harrington stepped onto Golden Gate’s freezing granite before dawn on November 24. She knew the terrain well and wasted no time in placing gear — they planned on climbing the Freeblast in four pitches rather than the usual 10. Harrington noticed her numb feet while lacing up her shoes, but a sense of urgency brushed away any hesitation. She was only 30 metres above the ground when she fell. With so little gear holding the rope close to the rock, massive pools of slack surrounded her midair and wrapped around her neck. After 15 metres of freefall she slammed into a ledge and flipped upside down. Later that day, anxious friends sighed with relief when they learned she had avoided a serious spinal injury. Though the gashes around her neck, forehead and arms could have been the macabre result of a mauling, Harrington sustained largely superficial injuries. Just the same, her season was over.

Harrington took a break from El Capitan in the months that followed. She went ski-mountaineering with her father in Ecuador, then had plenty of forced self-reflection during the first COVID-19 lockdown. She decided there was no reason to let the fear of her fall affect a future Golden Gate attempt but “I didn’t undermine the emotional toll that my big fall would take on me, so I was prepared to be more compassionate with myself,” Harrington says. She climbed on the granite crags close to her Lake Tahoe home when the lockdown lifted and reacquainted herself with placing gear and dealing with runouts. By the time she made it back to Yosemite in October 2020, her years of experience on El Capitan had unearthed a new confidence. “I was more ready than I ever have been,” she says. “I was really comfortable trying hard up high.” Harrington attributes some of this comfort to the 50 odd days she’s spent on its walls. This volume gave her the space to learn invaluable logistical shortcuts, including a few tricks for her old nemesis on the route; The Monster Offwidth. “[Off width] climbing is the complete opposite of what I enjoy about rock climbing,” she says. Rather than feeling the cadence of a steep limestone sport climb, or the grace needed for a blank slab, the 60 metre offwidth felt “burly and ugly.”

Part of this inelegance, however, came from Harrington’s size. At 5’2” with size 5 feet, her shoes were much too small to heel-toe cam like many of the men she climbed it with. In 2015 Harrington resorted to offwidth campusing; using her upper body exclusively for progress as her feet swam helplessly below. The technique wore a hole in her left elbow and grated most of the skin off of her shoulder. With more experience, Harrington knew she needed to make her feet bigger. Approach shoes worked with some success, but the soft platform made her feet weary. During a brainstorming session with Honnold they realized his size 9 shoes were a perfect match for the Monster. By giving Harrington his shoes to wear over top of her own, she would have a stiff and sizable pair of Russia nesting doll feet. Harrington harnessed her years of wide crack experience and climbed confidently through the slot — two hours faster than her 2015 ascent. She paused below the exit and carefully removed Honnold’s right shoe while wedged in the offwidth, and then danced up the delicate and unprotectable slab with lopsided feet.

Harrington climbed until the Tower to the People bivy ledge, with a mere two crux pitches to go, and switched partners from Honnold to her fiancé, Adrian Ballinger, who had rappelled in from the summit. While Honnold is likely the best person to simul climb the Freeblast with, she says, it was important to be with Ballinger when she began the multiple crux pitches of the route. He had supported her during the 2015 ascent and knew how to motivate her once they entered her second sleepless night on the wall.

Harrington reached the second to last crux pitch, the Golden Desert 5.13a, filled with a certain buoyancy. She felt strong and, in her element, finding a flow that had eluded her five years ago on the wall. Though she had never fallen on the insecure layback before, Harrington slipped off the glassy footholds while pausing to chalk up and ripped a piece below her. She rested at the belay for 30 minutes and tried again. This time, she grasped the flaring tips crack with intention and climbed above her high point. The Golden Desert arched left into an under-cling traverse; a particularly powerful sequence 30 some pitches into her day. Her foot slipped again and she was airborne; swinging headfirst into the wall before her vision turned black. Harrington says the fall was an eerie déjà vu to the year before. Her forehead struck a sharp granite crystal and burst open — painting the wall with a dramatic stroke of blood. Ballinger stifled the bleeding and found no signs of a concussion. “He told me I owed it to myself to give it one more go,” she says. Harrington rested again and fired the pitch.

Harrington reached the final crux, the A5 Traverse, with a determination that is rarely found in everyday life. “I went into that place you go into when you want something so badly and so deeply,” she says. When nothing else matters, there is little thought of failure. Harrington floated through the powerful sloping traverse and arrived at the belay in tears. They were several pitches below the summit, but Harrington knew what she had just achieved.

Climbing Golden Gate as your first free route up El Capitan is a rude introduction to the Big Stone. Freerider VI 5.12d/5.13a is an easier alternative to get to the top, and much less sustained. But for Harrington it was never about the easiest tick, “People told me that I was cutting corners in my progression, that I should do Freerider first,” she says. But the unsolicited advice just stoked Harrington’s fire; she became determined to climb “out of order”. Harrington says part of this confidence stems from the strong women who came before her in climbing — women like Lynn Hill who became the first person to free climb El Capitan via The Nose VI, 5.14a in 1993.

Hill returned a year later to free the same route again in a day. But Hill’s extraordinary goals were developed with a greater purpose in mind – providing women with more inspiration to get on the wall. “Our sport back then was directed by a fraternity of men, and there was little encouragement or, frankly, inclination for women to participate. Yet women climbers were out there,” she wrote in her memoir Climbing Free: My Life in the Vertical World. Despite the few prominent women climbers in Yosemite at the time, Hill is adamant that their definitive features were more than gender. “We were climbers. The fact that we were women, that was a bonus for the men around us.” Harrington says that her road to Golden Gate was in some ways paved by Hill. “I always grew up understanding that climbing was a space for women because of what she did. Where women could achieve just as much as men.” –