Five Things to Know About Back of the Lake

Learn the history to one of the best rock climbing areas in the Canadian Rockies

Photo by: John Price

Photo by: John Price

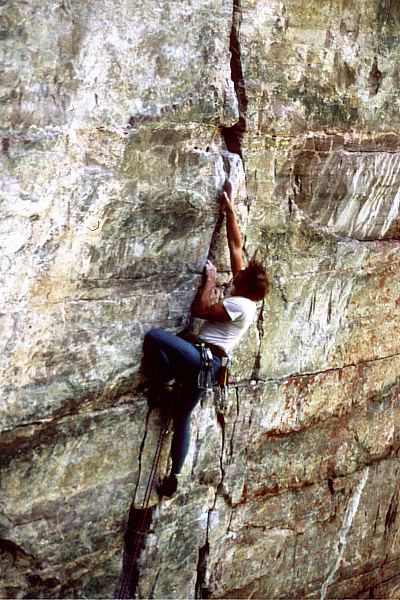

Rock climbing in the Canadian Rockies goes back nearly a century to when mountaineers would practice their skills on rocky outcrops at low elevations. Back of the Lake is a series of cliffs on the western edge of Lake Louise in the Bow Valley, Alberta.

Unlike other popular crags in the Rockies, Back of the Lake is composed of solid quartzite, which lends itself to fun and steep climbing. Climbers started to explore the crag in the 1950s and 1960s, they were often employees for Chateau Lake Louise.

There are dozens of high-quality trad and sport routes and a visit to the area is highly recommended. Below are a few things to know about Back of the Lake.

Walter Perren

Many of the climbers in the Canadian Rockies at that time were from Europe. Some European climbers were crafty with aid, some were quick to the summit, some were brilliant route finders, but one in particular was a phenomenal free climber: Swiss climber Walter Perren. He was known as the Spider of Zermatt. He would run around town bouldering on the stone walls of buildings, no one had ever done that before and people were surprised at his agility and fluidness.

Perren lived in the Rockies working as a mountain guide heading Parks Canada’s public safety program. On Mount Louis, he climbed a variation to the Kain Route called the Perren Cracks. Sometime during the 1950s, a pair of climbers from Europe came to the Rockies to make short films about the mountains and climbers who live in the area. They ended up at Back of the Lake with Perren.

At Back of the Lake, Perren demonstrated free climbing techniques for the camera, long before anyone established routes there. While no one knows what happened to the footage, the late Tim Auger said he’d seen it and that Perren was soloing up and down the route now known as Pub Night.

The Great Canadian Corner

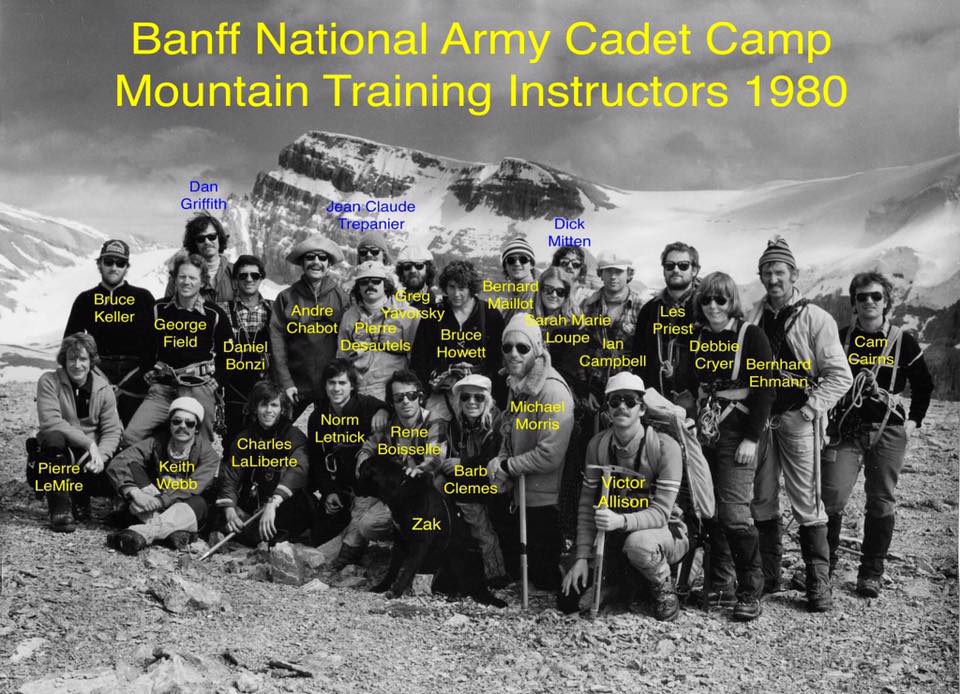

There hadn’t been much in the way of recorded climbs or grades, even though there had been some routes established by the late 1970s, but that all changed at the end of the decade. In the late-1970s, the Canadian Army Cadet Camp from Banff started to use Back of the Lake for training.

In 1979, two climbers from Quebec, Rene Boisselle and Louis Babin made the first ascent of The Great Canadian Corner and graded it 5.10b. The splitter crack rises above the tourist trail and is one of the best trad routes at Back of the Lake.

At some point in the following years, the climb was renamed Standing Ovation, the name it is now referred to in guidebooks. Many of the climbers in the image below went on to make dozens of first ascents in Canada of now-classic routes.

The 1980s

Climbing took off in the 1980s. Bruce Keller and Rob Rohn made the first ascent of Air Voyage, a 5.10d trad route up a steep wall. It was the hardest route at the time and signaled at the potential at the crag. Rohn went on to make the first ascent of I Hear My Train A Comin 5.10, Long Stemmed Rose 5.10, Crimson Skies 5.10 and Violet Hour 5.10. Climbers like Joe Buzowski, Marc Dube, Dan Guthrie, Ian Bolt, Peter Charkiw and Bruce Howatt started to climb harder lines, like Arc of a Diver 5.11c.

In 1985, Peter Arbic and Buzowski made the fist ascent of the now-famous Wicked Gravtiy 5.11a (the feature photo above is of Marc-André Leclerc free-soloing it). At the time, bolts were few and far between because of the effort required to drill into the hard quartzite with hand drills. Sometimes one bolt took five hours to drill.

The following year, Josh Korman the first free ascent of Scared Peaches at 5.12a trad, a now classic line. Then Korman freed Collodial Impact 5.12a and Howatt sent Mistaya 5.12d. By the end of the decade, the electric drill was introduced to the area and many of the first ascent teams retro-bolted their climbs as sport routes. The area’s popularity boomed in the 1990s.

The Path

In 2007, Sonnie Trotter sent The Path, a 45-metre trad line that linked Wicked Gravity into the wall above. The upper section was bolted over 20 years prior, but was subsequently abandoned due to its technical difficulties. Trotter had inspected the line on rappel and decided not only that it was climbable but also that an ascent would be feasible using trad gear. He chopped the old bolts. Five weeks after starting, he stuck the hard crux above run-out gear and climbed to the finish.

He later said, “By rapping in, I discovered that the route can and should be climbed entirely on natural gear, all trad. So after two days of top-roping the climb using cams for directionals, I knew for sure that it was meant to be climbed in a traditional style, not sport. So I went up and chopped all the bolts off. It was a hard decision to make at first because it is now rated R, but I have gotten a lot of great responses from people and it was ultimately the best choice to make. I then worked on the climb for about 10 days spread out over 5 weeks before redpointing it, placing all the gear on lead, and avoiding any fixed gear. It was the best style I could imagine doing and it was a great relief to finish it.”

It’s been repeated by some of the best climbers in the world, including Babsi Zangerl, Jacopo Larcher, Alex Megos and Jonathan Siegrist and the grade has settled at 5.14aR.

Hard Sport

The excellent sport climbing at Back of the Lake was featured on the cover of the fifth edition of Sport Climbing of the Canadian Rockies in 2002. The image was of a young Knut Rokne making a clip on Jason Lives 5.12d, a route established in 1990 by Marc Dube.

Other hard sport routes were added after Jason Lives, including Tsar Bomba 5.13d by Miles Adamson. In 2020, Braden Bester established The Empyrean, a 47-metre 5.13d, which got a second ascent by Sonnie Trotter – read about it here. While there aren’t many other sport routes above 5.13, a lot of potential through steep roofs remain.