Free Will: The Climbing Life of Jim Sandford

One of Canada's most accomplished and legendary rock climbers

In 1994, Jim Sandford clipped the chains on Division Bell in Cheakamus Canyon. The route’s 25 severely overhanging metres clocked in at 5.13d. It was just the second route on the Big Show Wall, which is more of a relentless, planar 45-degree roof than a wall. In 1993, Keith Read had climbed Gom Jabbar, 5.13b, a tour de force of its own. The year after Division Bell, Jim was back on the Big Show Wall to send Pulse, the first 5.14a in Canada. His wife, Jola, showed that she was the strongest woman climber in Canada by adding Freewill, a direct finish to Keith Read’s Gom Jabbar.

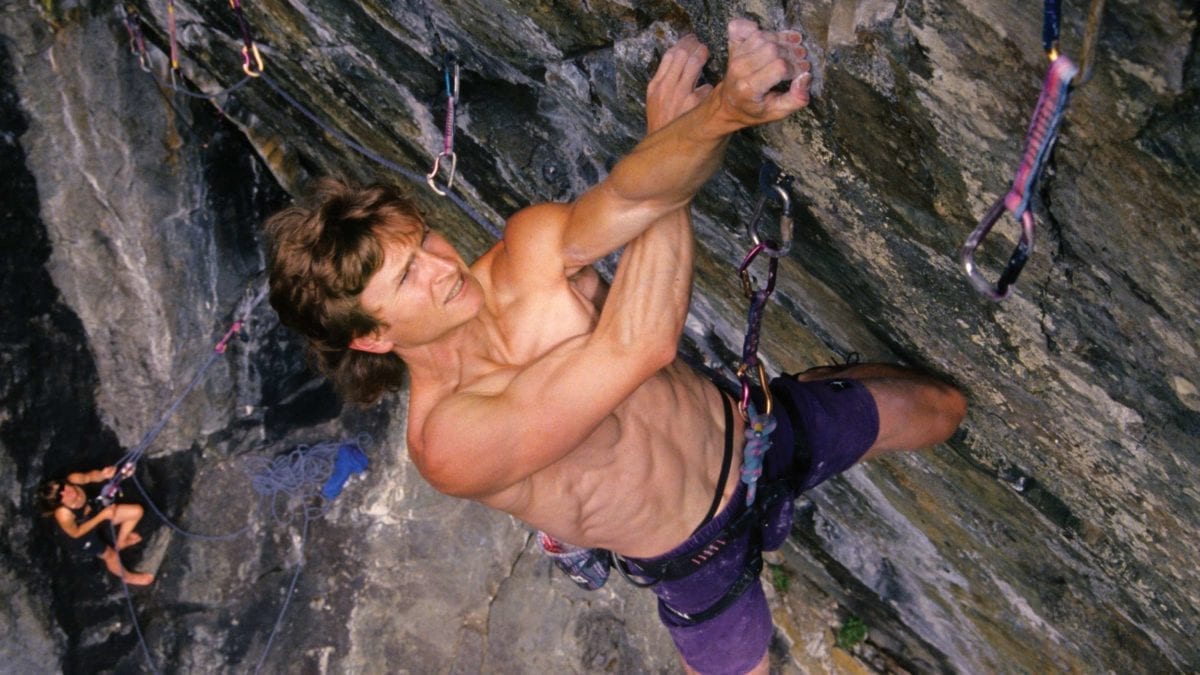

There were no other climbs in Canada like these, and Jim and Jola just kept climbing harder and harder routes at the Big Show Wall. Pet Wall in Squamish and many others in B.C. Photos of Jim working the routes explained his nickname “the Saran Wrap man,” which he earned because of his lack of body fat and the skin stretched tight over muscles honed by decades of training. “I’m an ectomorph,” Jim says, which is of course true, except for the muscles. Jola looked equally fit. These were no ordinary climbers.

And yet, these consummate acts of rock athleticism were connected to music that usually brought to mind dark basements clouded with pot smoke and Dark Side of the Moon playing at eleven on a bad stereo, rather than proud and relentless rock lines. Division Bell was the name of Pink Floyd’s 1994, 14th album. Pulse was named after Pink Floyd’s 15th album, released in 1995. The boxset had a CD case with a flashing red led.

‘Freewill’ was the name of a song from Rush’s 1990 album, Permanent Waves. Whatever you think about Rush, it’s a complex piece of music with five different time signatures, and what the lead guitarist, Alex Lifeson, said was the hardest he ever played. The chorus, written by drummer and the band’s resident philosopher, Neil Peart, ran: “You can choose from phantom fears / And kindness that can kill / I will choose a path that’s clear / I will choose free will.”

Rock and Rush. It’s an unlikely combination at first glance, but when you look at Sandford’s life and extraordinary climbing record, it all makes sense.

11-year-old Jim Sandford was a keen Boy Scout. At home he had heard stories of his father and his grandparents in the Raj. His great grandfather had served with the government forces at the Northwest Rebellion in Manitoba in 1886. His father had been a marksman in the British army and served with the Ghurkhas in India. If there was a theme to the household outdoor culture it was duty and tradition. Baden-Powell’s uniformed corps was an obvious outlet for Jim’s desire for adventure.

At Boy Scouts, however, Jim’s values and philosophies took a fateful detour unanticipated by Baden-Powell’s Scouting for Boys. “My friend in scouts, when I was maybe 13, said ‘Dude, you got to come over, I’ve got this cool album,’” says Jim. “I ride my bike over to his place after Scouts, and he has the album 2112 by Rush. There was a long song about a dystopian totalitarian future where a guy finds a guitar and music but when he takes it to the high priests, they crush him. I guess there was something that just really appealed in the complex story, the complicated time signatures. And the band was just doing their thing. The recording companies didn’t even want put out 2112, but the band insisted and it was great. I went, ‘I can kind of relate.’”

Two years later, at 15, when Jim was going through the usual adolescent tensions with his parents, Rush released Permanent Waves. “The song ‘Entre Nous’ [about how complementary objects often exist apart from one another] really helped me get through that period.” He would go on to see the band live seven times, to meet them personally and to be deeply affected by their music.

Jim’s climbing partner, friend, business associate, and fellow Rush fan Chip Miller from Metolius Climbing in Oregon puts it this way: “Rush is a band that appeals to those who don’t fit into mainstream molds, philosophically, politically. Climbing used to be a home for misfits too.”

“A year later,” says Jim, “when I was 16, I discovered climbing and my world changed forever.” Two weeks after his sixteenth birthday, Jim had a driver’s licence. The mountaineering course at the YMCA had imparted a bit crampon and ice axe technique and some rock climbing. Rappelling terrified Jim at first, but he made a harness from webbing he had bought from rei in Seattle and purchased a locking carabiner to go with it. He started bouldering outdoors at Fleming beach, did alpine climbing in Strathcona park, top-roped, honed his skills, lost some of his fear and discovered a talent he hadn’t known existed.

Jim fell in with a group of climbers from the University of Victoria and made his first trip to Squamish. “We did Slab Alley and Diedre on the Apron,” he recalls, “placing rigid stems friends, hexes and stoppers. From then on, I took any opportunity to climb.”

In 1986, Jim was a 24-year-old hopeful with eight seasons already under his belt. The Squamish climbing scene was growing, but Canmore was still the undisputed centre of Canadian climbing. Joe Buzowksi, Colin Zacharias, Rob Rohn and other hard rock climbers inspired Jim to climb harder on the quartzite at Back of the Lake and the dozens of sport climbing crags just getting developed. “They were super driven and psyched,” says Jim, “and I started pushing hard.” To follow his calling, he moved to Canmore.

Mountaineering and ice climbing were also major draws for the move, since Canmore was the epicentre of ice climbing at the time. Jim lived with alpinist Dwayne Congdon and did it all: limestone sport and trad, north faces, ice, Bugaboos alpine rock. He also became an ACMG rock guide and an assistant alpine guide, took outdoor rec courses at college and got hired by the Yamnuska Mountain School. It looked like he might become an eminent alpinist, but after a few hard seasons, Jim began to wonder if that was really where his heart was at that moment in his life. Often, he recalls, “I definitely just kind of wanted to get off [big mountain routes] after being vulnerable to objective hazards for a lot of hours. I think that didn’t quite appeal to me. I knew that there was so much out of my control.”

In 1987, he started going back the West Coast, not just to visit family, but more and more often, to climb at Squamish. “It was partly the atmosphere,” he recalls. Squamish climbers like Peter Croft, Bruce Macdonald, Kevin McLane, Perry Beckham, Dave Lane and Greg Foweraker were all pushing standards on the solid rock of Squamish, from short routes on the crags to the multi-pitch walls. “I worked a bit at MEC and then I ended up moving to Squamish, guiding and training,” says Jim.

It was an exciting and revolutionary era in climbing. Jim climbed in Smith Rock where a small group of climbers, including Alan Watts, Brooke Sandahl and Tom Egan, had spent the eighties turning an area a day’s drive from Squamish, into North America’s first sport climbing mecca.

They used European approaches, like rappelling down to place bolts and practicing a route before leading it. New, sticky rubber shoes, particularly the Boreal Fire from Spain, made it possible to climb on steeper and smoother rock. In 1988, the Snowbird International climbing competition was held in Utah, the first big European-style competition in North America.

“It was the ’80s,” says Jim, “I went to Europe and Smith Rock. Bolting on rappel was the thing. For a while there was this fear that one group was going to overrun the resources of another group, but the writing was on the wall for how I would sort of stake my claim in climbing.” Jim went to Europe in 1988, where he climbed at Cimai, Buoux, Frankenjura and other crags. “France was an eye-opener,” says Jim, because of “the amount of hard climbing and climbers.”

That same year, in October, Jim travelled to Yalta, on the other side of the Iron Curtain, for a Soviet competition. The trip was the idea of his climbing friend, Marc Dubé.

In the 1980s, Yalta on the Black Sea in Crimea was the main seaside holiday resort for the citizens of the Soviet Union. The steep limestone cliffs ringing the town had also become popular with rock climbers, and for Soviet climbers, competitions, held outdoors on real but heavily altered rock, were a highlight of the climbing season.

Jim and Dubé were the only North Americans at the comp. With his brightly-coloured 1980s climbing clothes, muscular physique and long, curly mane, Jim must have stood out from the average Soviet climber as young Jola Siwiec of Poland boarded the bus to the competition.

“There was no one else to sit with,” says Jola, who sat down beside Jim. “I couldn’t speak much English, and he couldn’t speak Polish, so we just kind of looked at each other.”

Jola had come to the competition with a contingent of strong climbers. They were a cohesive group that had climbed together on rock, in the Tatras and the Dolomites and on the desperate winter mixed routes of the Tatras. Polish climbing was in a heyday, with brilliant climbers like Voytek Kurtyka, a superb rock climber who could also climb hard high in the Himalayas, and Jerzy Kukuczka, whose capacity to suffer and endure risk and hardship inspired a generation of Polish climbers. But most Polish climbers, like everyone else in Poland, were short of money.

“I didn’t have equipment,” says Jola. “I made my own harness on a sewing machine. I didn’t have climbing shoes, so I used sneakers, and then soccer shoes with the cleats cut off and rubber glued on the bottom by a shoemaker.” Passes to climb in the west were, needless to say, rare, compared to the access granted to Soviet states, but even Soviet competitions allowed them a chance to meet western climbers.

Jola knew enough English to invite Jim to the Polish team’s nightly bridge and tea-drinking session. Raised in Victoria by an English family who loved bridge and tea, Jim fell in with the Poles right away.

“It had never happened to me before, but I just clicked with them,” Jim says. “Like them, I had grown up with stories about World War II, about the rise of fascism and then the war itself.”

The Polish climbers still lived behind the Iron Curtain, under the Soviet control that had been promised to Stalin in Yalta itself in 1945.

Just as importantly, like Jim, they grew up addicted to drinking tea and playing bridge.

“We listened to Led Zeppelin and the Doors,” says Jola, “We played cards and looked at each other. Climbers played a lot of bridge waiting for the weather to improve in the Tatras. I was a better player than Jim, but he was really nice and sent me flowers.”

Neither Jola nor Jim won the competition, but neither of them would remember the climbing as the most important thing that happened in Yalta.

They corresponded over the winter of 1988, and Jim visited Jola in Bielsko Biała near Krakow in the spring of 1989. In the spring and summer of that year, there had been peaceful protests against the Polish socialist government in throughout Poland and in Jola’s town, followed by the famous strikes in the Lenin Shipyards that spread throughout Poland and became the Solidarity movement. While a June election was promised, no one knew whether it would herald a new era of Polish democracy or see the country back in the hands of the communists.

Jim went back to Canada and returned in the fall.

“We planned that I would sponsor Jola to come out to Canada as my fiancée,” says Jim. “Poland was still behind curtain, just starting to open up, so there were challenges.” He went from office to office to fill out the papers, which must have been epic, since in his words, he had “learned very little Polish and there are seven forms of nouns. Grammar is epic.” Luckily, most of the administration was at the Canadian Embassy.

Before they left Poland, the Berlin Wall came down.

“Once I arrived in Canada in December ’89, in order for me to obtain landed immigrant status, we had to get married within 90 days,” says Jola. “I knew that I had to get married and not go back. But I wanted to be with Jim.”

British Columbia, with its vast forests, the modest town of Squamish with its pulp mill and the rain all took some adjusting for Jola, and for a while they couch surfed at family and friends. Jola had come from a strong community in Poland which she naturally missed.

Adjusting to a new country is more difficult than many Canadians assume. She says, “Growing was a good life actually, a simple life, so you didn’t have to make a lot of choices. Apples in winter, cherries, plum in September, when pears come, you eat those, I thought it was very wholesome. I went to my grandmother’s for summer holidays. Everybody had to work. We didn’t have much money, but we all had something to do.”

The Yalta comp had another, less spectacular benefit for Jim. Even with a single competition under his belt, he was one of the more experienced comp climbers in Canada. Jim won a climbing competition in Canmore in which American sport climbing ace Tony Yaniro was one of the competitors. “’Here’s your prize,’ they said and put a Hilti drill in my hands,” says Jim. It wasn’t long before Squamish’s incredible rock scape provided Jim with the inspiration to use his new drill. In 1988, he spied the stunning overhanging arete on the left side of the Bulletheads formation that would become Eurasian Eyes, 5.13b and never turned back.

The energetic rock-climbing scene in BC provided Jim and Jola with more than enough rewarding projects. In 1990, Squamish climbing was just beginning to claim its rightful place as a granite climbing era second only to Yosemite. Long hard trad routes, to short crag moderates and everything in between proliferated, but that winter, “everything was wet,” says Jola, “so all we could do was look at things,” and, at first, she didn’t like Rush.

Spring came, 1990 came, and with it, exciting developments era in climbing. The Edge, the first climbing gym in B.C., opened and introduced many new climbers from Vancouver to the world of sport climbing. Bolting on rappel was becoming more accepted, although there were still opponents. Jim’s climbing partner, Josh Korman, ironically pasted a “hangdogging is a disease” bumper sticker on his vehicle, while he threw himself at a number of vicious sport climbing projects. Along with Dave Lane, John Howe, Perry Beckham, Mike Orr, Kevin McLane and others, Jim and Jola contributed to the sport climbing development of cliffs like Petrifying Wall and then the overhanging limestone of Horne Lake on Vancouver Island and dozens of other cliffs. Bouldering in the forest beneath the Grand Wall became a major activity in its own right.

Jim’s reputation grew, but his motivations remained largely personal. “I just wanted to climb harder and better, and that’s what drove me,” says Jim, “I didn’t know where I was going with the whole thing, I was just pushing to do what I wanted to do.”

Perry Beckham, a long-time Squamish climber, met Jim in 1985. Together, they formed Pacific High Mountain Guides and spent their spare time developing the early sport climbing scene at Squamish. Beckham, whose reputation for hard climbing of all styles at Squamish is legendary, says “from the get-go, Jim was a stronger climber than me. Pet Wall was where sport climbing [at Squamish] started,” says Beckham. “We were balancing out rap bolting with the traditional ethics we got from English rock climbing and Yosemite. If we had a bolt, we’d follow it up with a runout or a nut. Jim showed us the complete sport climbing approach and carried the legacies of Weinstein and Croft into sport climbing. If I was to choose one word to describe Jim, in every aspect of his life,” says Beckham, it’s disciplined.” That discipline was soon to meet its greatest challenge yet, not at Squamish, but on the Big Show Wall of Cheakamus.

The Efforts of Keith Read, Jim and Jola made it a hotbed of sport climbing. “It’s an amazing wall,” says Jim, “and it was a big part of a couple years of my life. That was the period when holds were manufactured. It was brief, has stopped as far as I know, I don’t regret shit, it was the zeitgeist.”

Some of the new energy in climbing emanated from Smith Rocks in Oregon, where Alan Watts had introduced European style sport climbing. 1992, Jim had written a letter to Metolius to see about getting sponsored with a climbing harness. They didn’t sell harnesses in Canada so they weren’t keen, but, said if Jim got their harnesses into some stores, they would sponsor him. “Motivated to get sponsored,” says Jim, “I got a box of sales samples, took them to shops, and the stores bought the gear.” He is still a rep for Metolius to this day.

In 2000, Jim and Jola’s son, Oscar, was born. “We didn’t want to be 85 years old saying ‘God, we I should have had at least one kid.’ The window was starting to close.”

Jola stayed home to look after Oscar, and they both switched off climbing duties to keep climbing hard. “You bring a child into play and it’s definitely not all easy to stay together,” says Jim. “A lot of my friends are not together. People change and grow. [Jola and I] were fortunate in that we were raised in a time when things were more traditional. In today’s society that’s not so much the norm, both people work, two workers create stress. Probably the secret was continuing to climb. Jola is my best friend. What has kept us together? The outdoors, hardship and adventure, climbing has been a bond. Life is so incredibly rich with a son. Nothing compares to it. I spent a lot of time with him. He’s me and Jola’s best friend.”

Now Oscar is 20 years old and in his third year in computer science at the University of Victoria.

Jim trained hard at the Edge in Vancouver. Then he injured his rotator cuff and was shut down by Silent Menace, a sport climbing project in the Cacodemon Boulders below the Chief. In 2001, Sonnie Trotter made the first ascent and graded it 5.14a. Jola also slowed down for a while.

In September, 2002, Jim went to Rush’s Vapor Trails concert in Vancouver. The band had been inactive since 1997, when drummer Neil Peart’s daughter had died, followed by his wife the next year. Singer Geddy Lee commented that the album was partly made to help those who had suffered personal losses or suffered from psychological set-backs. It was an early CD recording and many fans, and the band, were critical of the sound, but the album came at a crucial time for Jim, who attended the Vancouver concert.

“I was second row, centre stage,” says Jim. “It was incredible to see the musicians up close. So much skill, energy and enthusiasm pursuing their passion.”

In what Jim describes as a “sweet miracle,” his friends Ben and Paul had given him passes to meet the band backstage after the concert. “Ged doesn’t say much at end of concert,” says Jim, “maybe because of how his throat feels after all that singing,” but also, perhaps, because it was the 26th show on a 67-date tour. “Alex [Lifeson, the guitarist] is a big dude. He’s hilarious.”

A reviewer in the Province the next day said that Rush had “played like demons,” but joked that the long-distance runners of the Canadian rock scene might possibly be on an “interminably long spin cycle.” For Jim, however, their determination to continue their careers in the face of the ravages of time and changing taste was a model of discipline and commitment. The album was also a bittersweet gift in the year that his father died.

“My father passed away from lung cancer in a period of three weeks,” Jim says. I watched as his body shut down.” He quotes the song ‘Vapor Trails’ when he remembers that time: “All the stars fade from the night / The oceans drain away.” Jim attended his father as he died. Afterwards, to come to terms with his loss, he became curious about two of his father’s pursuits. As a young man, his father had raced motorcycles and sidecars, in the army, he had been a marksman, but he never shared these skills with his son. “Maybe if I tried those things,” said Jim, “I would somehow have a spiritual connection by experiencing what he wouldn’t teach me, maybe because he was afraid these activities were dangerous.”

Jim got a motorcycle and enrolled in shooting courses. He has an affinity with weapons that may be partly accounted for by his genealogy, that shows that he is descended from the Viking Rollo Ragnvaldsson (The Ganger), 1st Duke of Normandy, who is depicted in the Vikings series on television. Soon, he was competing in speed and accuracy events. “Shooting isn’t the most popular pursuit,” says Jim. “It’s got bad press, but that’s too bad, because it’s fun.”

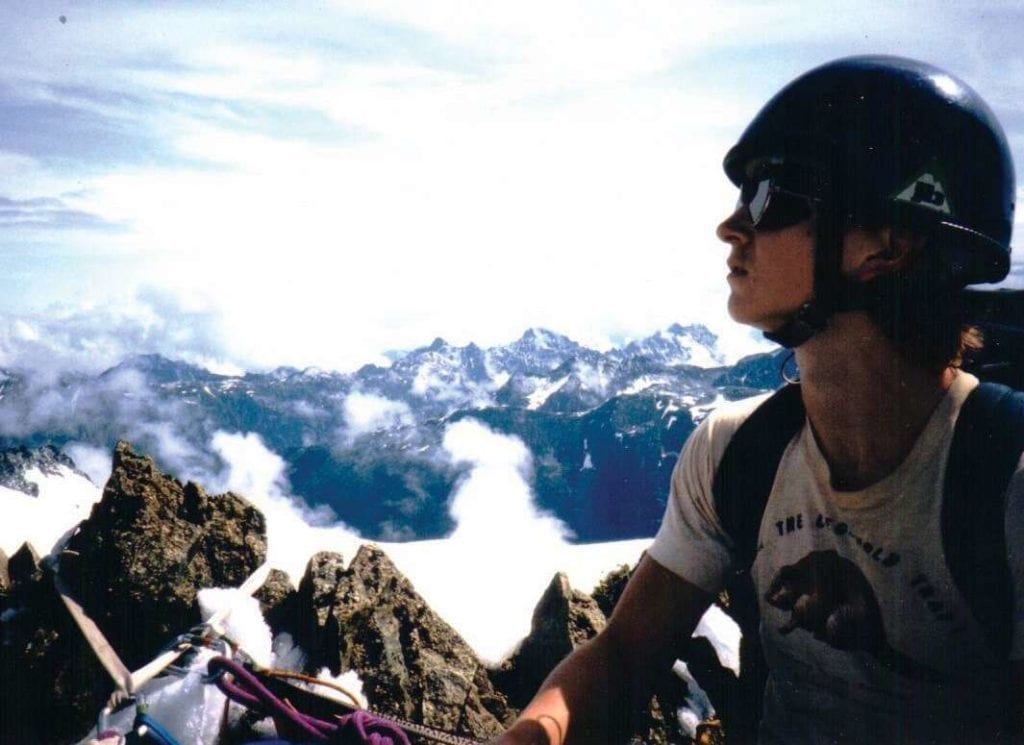

In 2006, Jim returned to the alpine to run. “Your climbing performance slows down; you can slow it down but you can’t stop it, but your endurance is still there,” he says. He won some races, figured out his lactate threshold, training zones and won some trail races. Soon, however, he decided to take his fitness to the hills. “I got into scrambling, took endurance to the mountains onto class 3 and 4 terrain,” says Jim. “I had no particular goals, but it was really cool to move fast and light.’ On Mount Sir Donald, he scrambled past roped parties on a route he himself had climbed when he was 19 years-old with a pack and rope.

Then, in the spring of 2019, on Alpha Mountain near Squamish, he fell. He had been scrambling the East Ridge with Jola, when a block he was standing on slid out form underneath him. “I rag doll-tomahawked 30 metres down a gully and stopped on patch of snow where I clawed into it like a cat,” says Jim, “I continued a down a bit, then I realized I wasn’t just scraped up but I remembered a nurse telling me that you have 60 minutes of natural drugs, [after a serious accident], then you crash. I started feeling shitty and we called for a rescue.” The helicopter whisked him to the hospital where he got stitches in six places and found out he had edema in his knee.

“It was a wake-up call after 40 years of climbing,” says Jim. “I’ve gotten over it. I did some more soloing, but the accident made me much more aware that things can be dangerous because they’re easy.” Jim still climbs at a level that few climbers will ever achieve and runs in the mountains with Jola, but part of his enjoyment now comes just from the process of getting outside and keeping fit. He’s also happy to go down to the shooting range with his old friend Perry Beckham.

Chip Miller says that Jim is possessed of a timeless energy and stoke. After a fast send of the Grand Wall, Miller was ready to decompress on a leisurely hike down, but Jim was quickly coiling the rope for a brisk downhill run back to the car. “Often, after spending all day doing clinics with our products in gyms,” says Miller, “It’s nice not to go out and rage all night. Jim wants to climb until the gym shuts down…he’s operated at a high level and is still capable of physically executing at a high level in the sport.”

Looking back on his extraordinary life in climbing, Jim says, “I found this thing and really got into it. I don’t know why. My parents didn’t do athletics. Sometimes adventure skips a generation maybe. My grandfather hunted tigers in India. Climbing is freedom of movement on the mountain. That’s the be all and end all. There are no rules, just making your own decisions; freedom, for those who like it.”

This story originally appeared in the February/March 2021 issue of Gripped: The Climbing Magazine