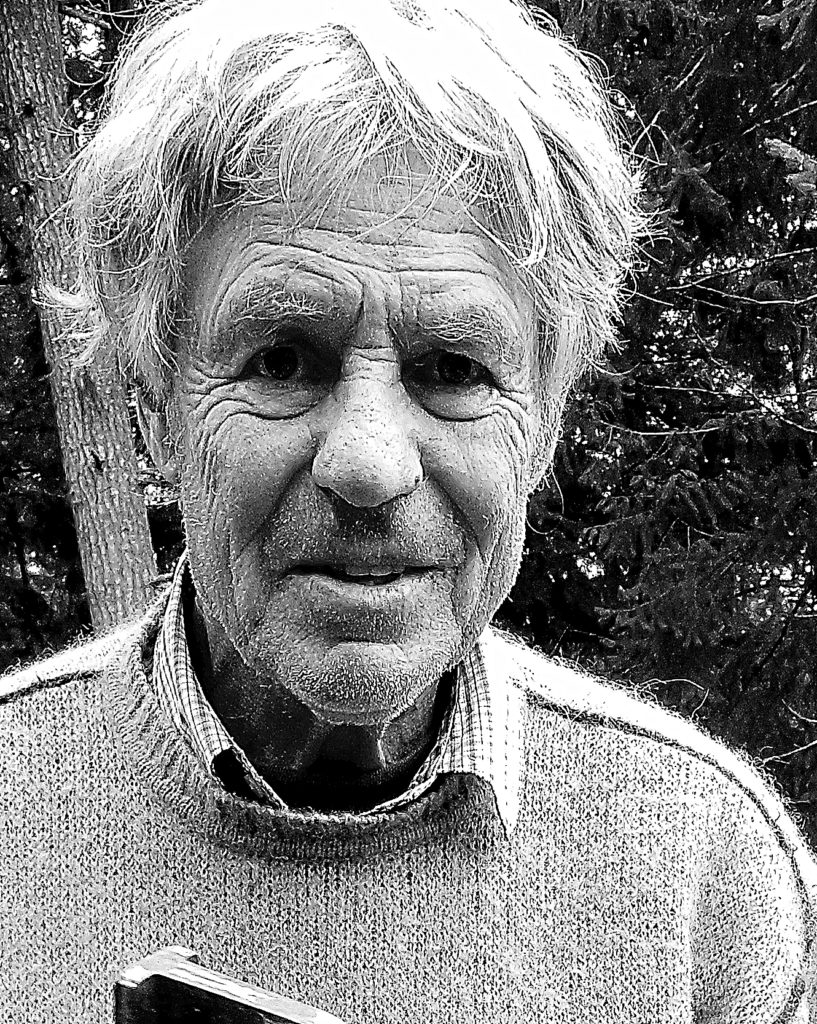

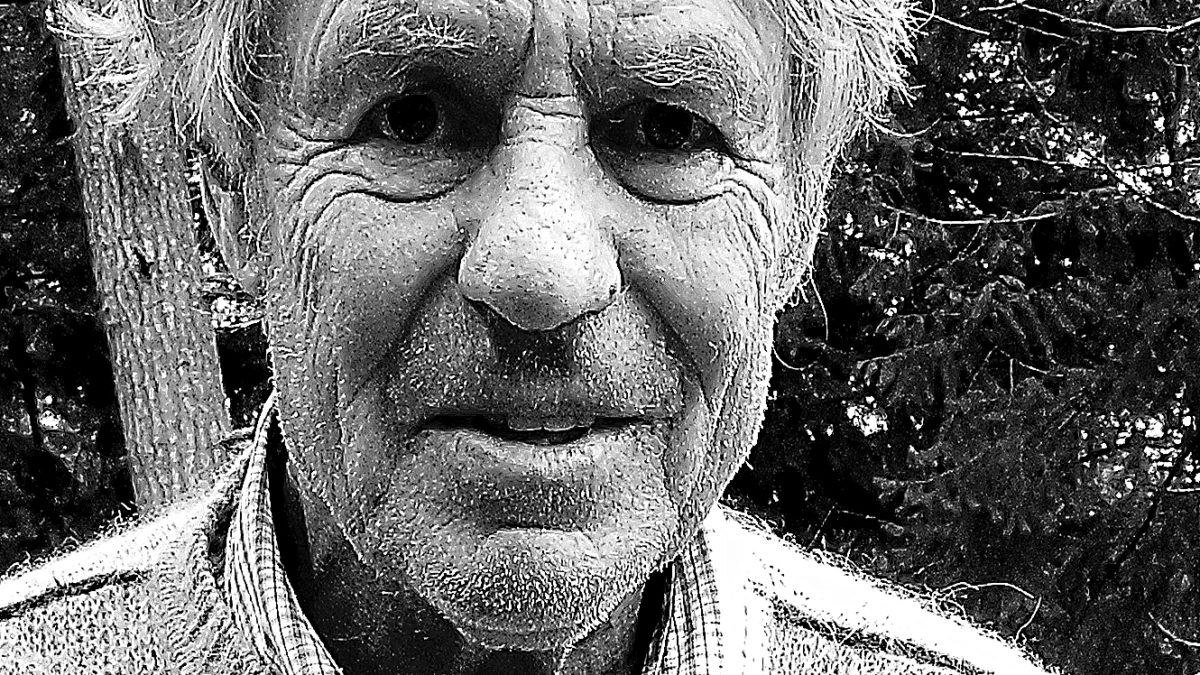

Rob Wood: Legend, Pioneer, Activist, Hippie

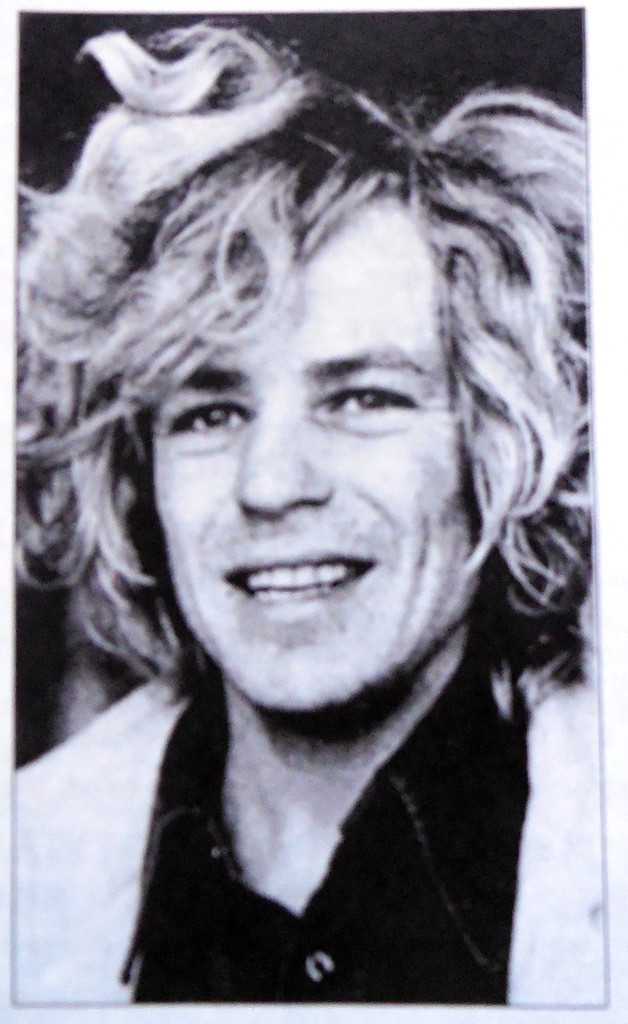

Rob Wood was one of the pioneers of ice climbing in Canada. After four decades of living on a small West Coast island he spoke to Gripped editor Brandon Pullan about his life and adventures.

“Cheers,” said Rob Wood, “today is the fifth anniversary of my heart exploding and me dying five times.” Shocked by his words, I raised my can of Lucky Lager beer and, speechless, I smiled. Rob was on his boat, a home-made catamaran named Quintano, when he fell backwards onto the bed with chest pains.

Reaching up, he found the VHF marine frequency radio and gave an all-out, “Mayday, mayday, mayday.” A neighbour heard the call and phoned Laurie, Rob’s wife, who was up the hill in their self-made house. Laurie ran down, neighbours boated over and a coast guard helicopter responded. Within an hour, Rob was in a hospital and two days later he had died five times, but was expected to make a nearly-full recovery.

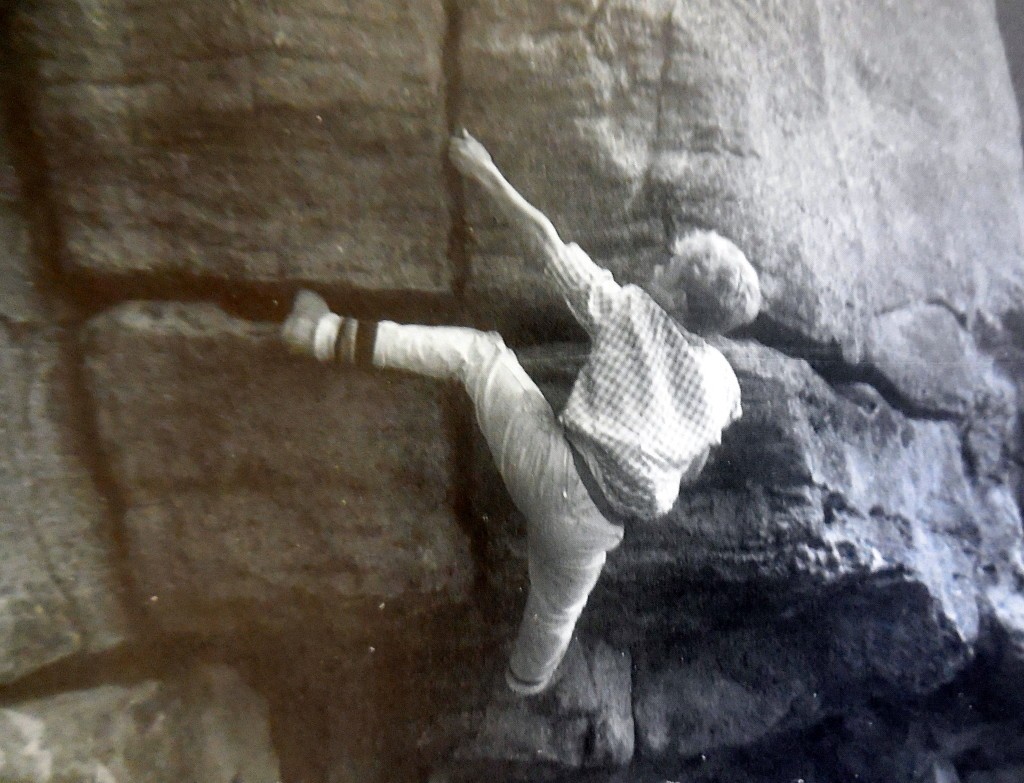

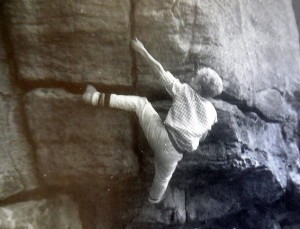

Rob was born and raised in NorthYorkshire, U.K., and started rock climbing at the age of 14. He attended the Architectural Association School in London and became an architect before arriving in Montreal in the early 70s, then on to Winnipeg and eventually Calgary.

“In the summer times, we explored the Rockies and climbed some new routes. Every time we went back to Calgary on Sunday night, we had a hollowness in our guts. The contrast with the reality we knew in the mountains became too much. I soon left the city.”

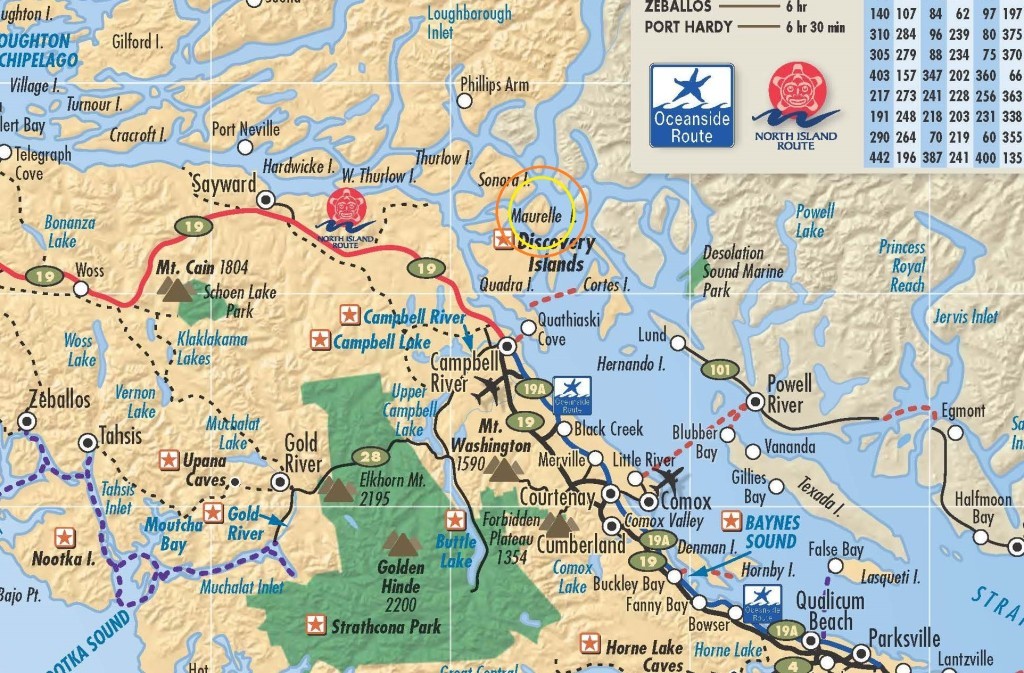

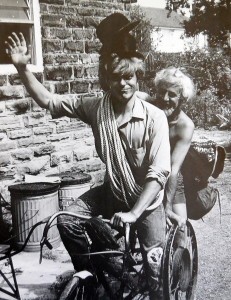

Rob found his way to the West Coast as a self-described “hippie” and settled on Maurelle Island. Rob’s architectural thesis was an academic criticism of modern cities with their greedy demand for resources and their destruction of and alienation from nature. Rob dreamed of a global pattern of self-sufficient villages which are connected with and evolved from their ecosystems.

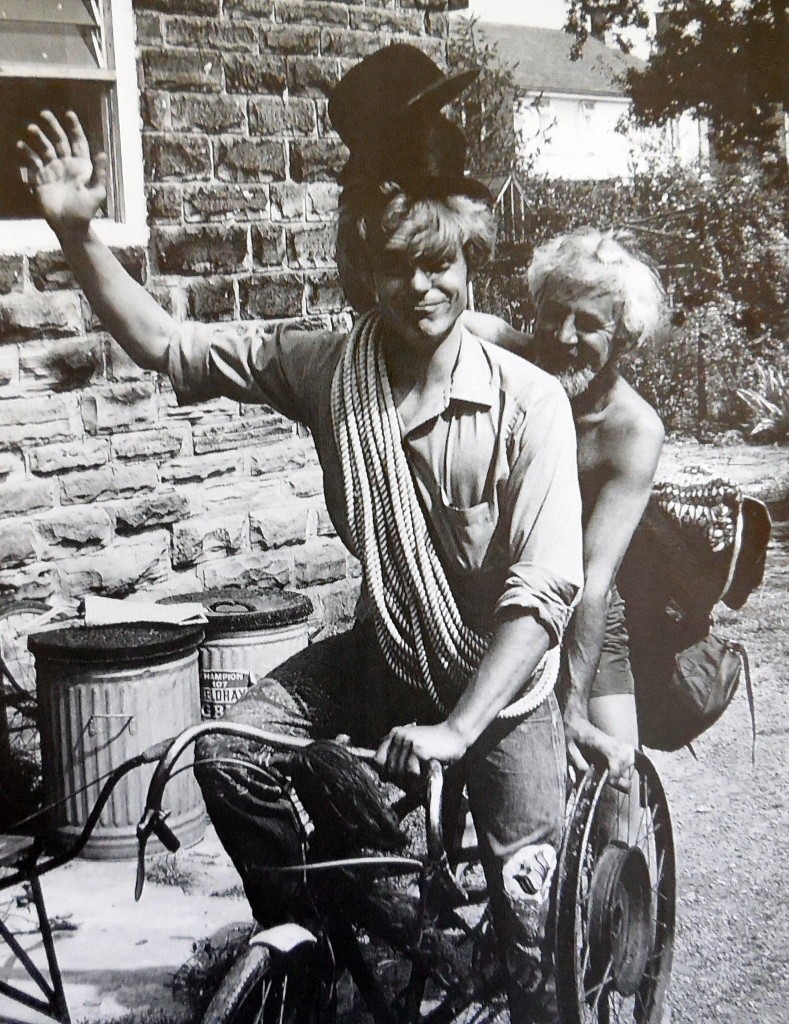

The famous climber Doug Scott said, “It was Rob, on our first trip to Baffin Island, who prompted a conscious and systematic self-examination and started a process which may go on for the rest of our lives.” Scott and Rob made a number of expeditions together, including one to the top of Waddington and one up a new route on Vancouver Island’s most impressive alpine face: Colonel Foster. “We agreed that the only changes of lasting value occur when we as individuals modify our own desires for fame,” said Scott. “Fortune and power over others – control our ambitions and ‘that ardent desire for distinction’ and come to terms with our inner nature.”

I first heard of Rob when I moved to the Rockies in 2004. He made first ascents of now-famous routes such as Weeping Wall, Cascade Falls, Bourgeau Left, Takakkaw Falls and others. A famous photo of Rob with Jack Firth, Tim Auger, Bugs McKieth and John Lauchlan hangs on a wall in a local pub. After hearing about Rob, I read his book, Towards the Unknown Mountains.

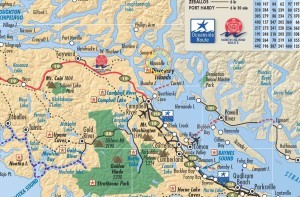

I contacted Rob because I had questions about a story I was writing about his friend Billy Davidson. Rob told me to visit him if I wanted the answers. After two ferries, I parked at the end of an 80-kilometre dirt road on Quadra Island, east of Vancouver Island. I walked down the trail, careful not to slip on the damp rocks, and got my first glimpse of Rob. With a black rain slicker on, he sat in his three-metre aluminum boat at the end of the dock. He was hunched over with water dripping from his hood. As I approached, he pulled the hood back and smiled, giving a big welcoming wave. He said, “I see you packed light,” as I only had a day pack. I was intending on staying for a few hours and returning by dinner.

Rob steered us through the Surge Narrow rapids, a trip he first made in 1975 when he moved to the island. After 10 minutes, we pulled up to his 15-metre dock that had crab cages and otter poo on it. We climbed out of the boat and Rob led me up the hill, an old logging road, towards his “property.” His house was bigger and more modern than I expected. Rob said, “Don’t know what you know about me, but my limp is from a stroke I had a few years ago after my heart exploded. I’ve lost my confidence in my body.” Rob was slow, but steady. Everything I looked at, Rob had made. “We’re the only full-time residents now, the other nine families visit sometimes or never at all,” Rob said refereeing to the other people who bought into the co-op in 1974. Ten families paid 3,000 dollars each to buy an equal part of the co-op. The island had only trees when they moved there. Rob sounded almost sad when he talked about the other families that had left, their properties were “going back to nature.” Robmisses having people around.

Laurie was away working on another island for 10 days. The 2008 recession forced Rob to close his architecture company. Sometime after his heart problems, Rob’s boat Quintano burned down. Within two years, he had lost his company, boat and ability to use his body to its fullest. It did not dampen his spirits. As we walked around, Rob said, “That’s where the cosmic cabin was, we had some wild parties there. We used it for kindling once the new place was built.” We walked over to the chicken coop, “Seven chickens, we once got an egg for every chicken, but only a few a day now.” We strolled over, Smokey the cat with us, to the large fenced-in garden, “We are totally self-sufficient for some things.” There were dozens of ripe tomatoes, bushels of garlic, large zucchinis, onions, kale, peas and so much more. We filled a basket for dinner.

After dinner, Rob said, “You should stay the night, I have lots more to tell.” He showed me his story in Mountain 4 titled The Sorcerer’s Apprentice. It was about his and Mick Burke’s ascent of The Nose in 1968, it was the first Canadian/British ascent and the 15th overall. Rob recalled, “I gazed up, what would five or even six days up there in such heat and discomfort be like? I thought of all the climbers lazed in the meadow, looking, calculating their chances, as I was doing. Shivers went down my spine as I pondered by what possible, audacious notion I imagined I could succeed where so many others had not.”

Rob then went on to talk about his trip to Baffin Island, “We wanted to break away from the highly structured organization of modern climbing expeditions. The danger, hardship and freedom from distractions encouraged us to delve deeper into our inner resources. The most lasting and rewarding experience of all was in committing ourselves to spending so much time in those beautiful and exciting mountains.”

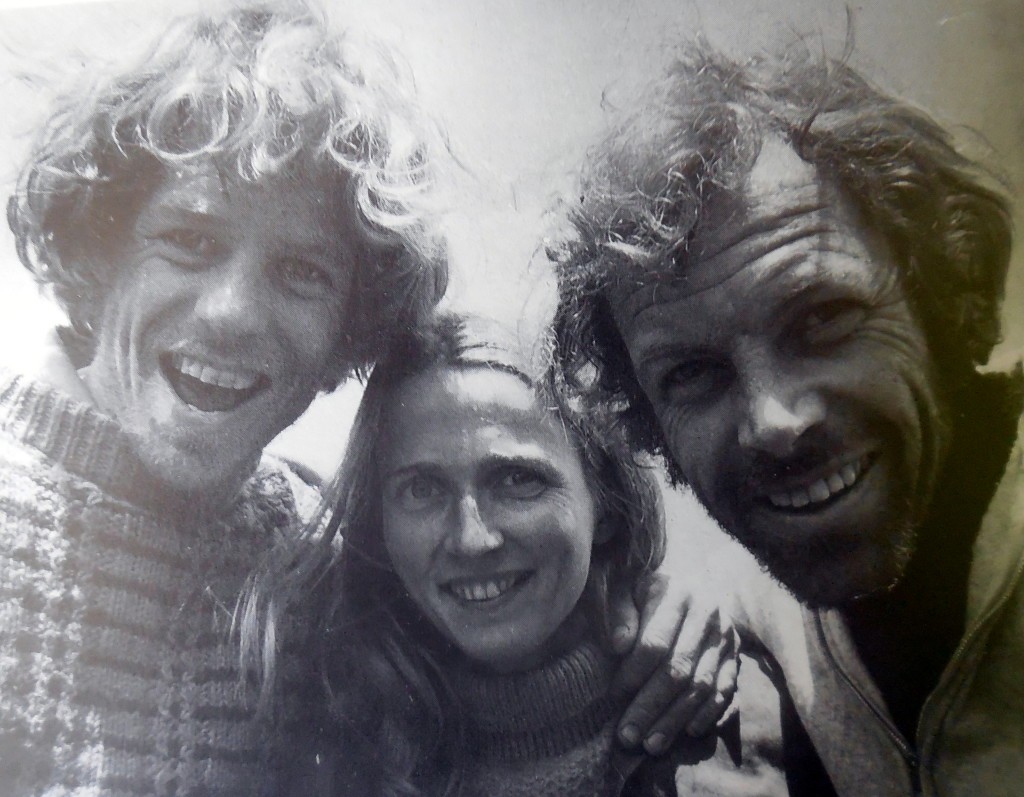

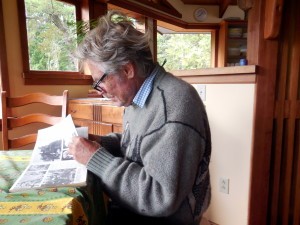

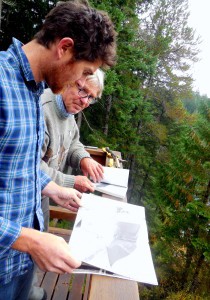

Between Rob’s stories of personal adventures I got my answers to the questions about Billy I was looking for. Rob and Billy fell in love with the West Coast on a trip on a sailboat to climb Waddington, they did not make it, but Rob returned later with Laurie and Scott, “The petty preoccupations of everyday, ‘normal’ life had been washed over the remote horizons of our consciousness, replaced by a mellow, ebullient and infinitely profound sense of harmony and peace,” Rob said about the trip while showing me a picture of the three of them after their climb in 1978.

We talked about the combined West Coast community effort to save Strathcona Park from mining and forestry in the 80s and 90s. We talked about the good ol’ days of raising his family on Maurelle Island. “The movement we all dreamed about is gone, everyone is too focused on themselves, not the community. So I find myself drawn back to the climbers of today, the people who share my values about the mountains. I have lost 40 friends over the years to climbing, but I’m drawn to it.”

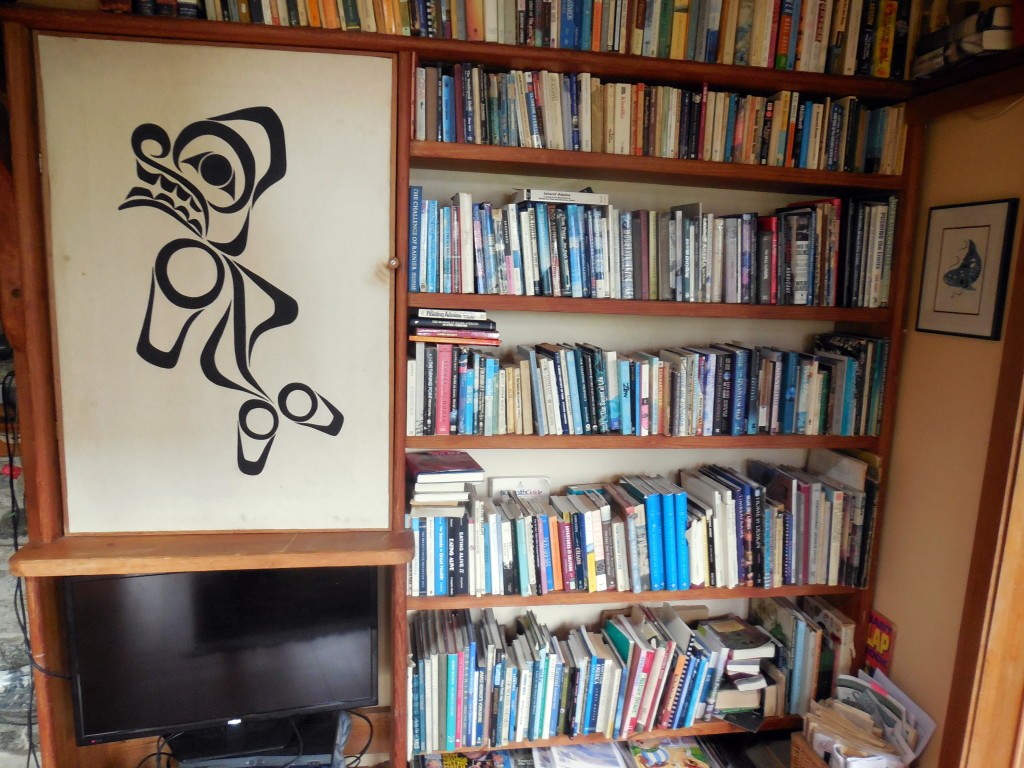

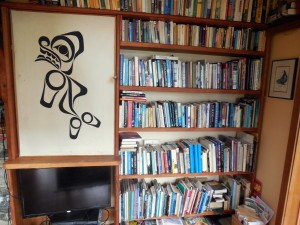

As midnight approached, Smokey the cat slept on my lap and the rain intensified. Rob sat in his chair, his library of books behind him, trying to remember more to tell me. “As mountaineers we have learned that in order to survive and enjoy the dangers of our environment, we must tune in and listen to the unconscious and intuitive messages emanating from the natural world, connecting with our inner selves and telling us what we have to do.” He finished with, “All I have now are my stories and I want to tell them, see you in the morning.”

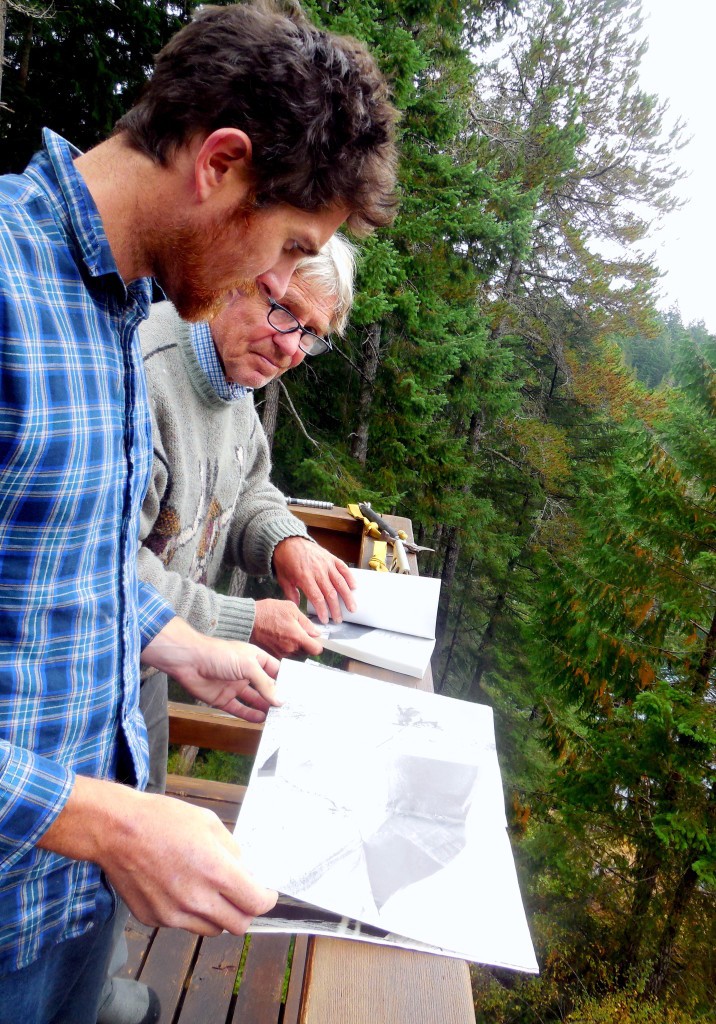

The following morning I walked in to find Rob sitting in his chair staring out the window, coffee in hand. “There was once fisherman and families boating out there, but now the fish are gone and families don’t seem to get out.” We looked at some of his old climbing equipment before we left for Quadra. I did not want to leave. “Are you sure you don’t want to stay?” asked Rob. Boating away from the dock, I looked back and pictured a beach with children playing and a busy dock with Rob’s family and boat Quintano. I thought of Wood in his prime, a man capable of anything. We cruised along the Narrows back to the dock by my car. The rain stopped and Wood took his hood off and said with a youthful tone, “Good luck with your story and come back soon. Off I go again.”

Over the years, my climbing experiences become much richer every time I meet a climbing pioneer. I went to visit Rob because I had one question. When I left Maurelle Island I had a recorder with more than 14 hours of stories and 100 new questions. Rob is the only real “hippie” I have met. He practices the environmental and community lessons he preaches. He said he would be happy to have anyone visit, help around the garden and live in his spare cabin. I will surely be returning.

I will finish with words from Rob after he made the 15th ascent of The Nose, “This pitch was a superb finish to a great climb. One minute we were on the wall, accustomed by now the three thousand feet of exposure and the unrelenting verticality, the next we were on flat ground. We were greeted by friend with fruit salad and beer – mere preliminaries, of course, to a real Yosemite orgy.”