Rockies Climber Andy Genereux on an Evolution of Style

One of Canada's most legendary route developers talks about how climbing changed over several decades

Andy Genereux’s first climb began on a frigid early spring day in the front range of the Canadian Rockies, with his home in Calgary just out of sight beyond the hazy foothills to the east. April in the Rockies can feel more like mixed climbing weather than the time to pull on rock barehanded, but Genereux’s high school classmates were to receive school credit for climbing on Mount Yamnuska’s grey and gold flecked flanks, and with a trace of sun surfacing through the scattered flurries throughout the day, Genereux wanted to make his first time count. Renowned local climber Ben Gadd volunteered to help guide the school group, climbing a new single pitch route on the cliff’s eastern edge for a challenging top rope to play on. Genereux was the only student who could follow Gadd’s lead in sneakers. That initial day of climbing in running shoes set a tone for Genereux that lasted his 47-year climbing career (and counting). A minimalist ethos and a sense of adventure paved the way for over 2000 first ascents throughout western Canada, including some of the first 5.12s in the Rockies and unrepeated alpine horror-shows.

Genereux began climbing in earnest with school friends, local climbers and — if no one could be bothered — himself. In an era when the leader was chastised for falling, free soloing came naturally to him. Genereux often drove to a nearby front range crag, Wasootch Slabs, to climb up to 20 pitches a day alone. He hesitates to use the word “pitches”, referring to the laps up to 5.10+ as 35-metre “highballs” — but you can do the math. “I didn’t fall for the first five years I climbed,” Genereux admits. He devoured large servings of limestone solos at any opportunity. The movement was fast, the exposure exhilarating and the pace all his own. Genereux recounts a memorable day of climbing alone in his early days; he pointed his car west alongside three high school friends and drove to Mount Yamnuska. He gave the trio his rack and rope for the seven pitch Kings Chimney and began climbing Unnamed 5.7 210m to its left. It was a brilliant summer day to be up high and Genereux up and down climbed routes all day while checking in with his high school friends on Kings Chimney. After his sixth route, the friends topped out and Genereux collected his borrowed rack. To his dismay his favourite hex was missing; it was forgotten at a belay mid route. Not wanting to leave booty for the next party, Genereux down climbed the face yet again and retrieved it. By day’s end, Genereux had free soloed seven routes with difficulties up to “solid” 5.9.

Genereux met Rockies climbing legend John Lauchlan at Wasootch several times. Their rock prowess mirrored each other and they pushed themselves on the “highball” circuit. Despite being five years his junior, Genereux kept pace and engaged gently with the friendly game of competitive soloing. “But back then you didn’t do a move you couldn’t downclimb,” he says. Genereux’s mental fortitude strengthened with each ropeless smear and glance of exposure beneath his feet. In the following years Genereux put up many routes on Yamnuska in a bold, ground-up-or-bust style that enabled him to climb on the infamous walls throughout the Bow Valley. Some of his most indelible climbing memories were perched high on multi pitches — he strived to establish his own.

Genereux and his partners climbed many serious new routes throughout western Canada in the late 80s. They endured nauseating runouts, terribly loose terrain and enough rockfall to make more than one partner run away to greener, granitic pastures. The fall of 1988 remains both a high and low watermark for Genereux. “It was like the pinnacle of bold 80s alpine rock climbing,” he says. Three major alpine rock climbs went down for Genereux: General Pain 5.11d A3 300m on Yamnuska, the West Face 5.11R 650m on Mount Robertson and The Warrior 5.10 X 550m on Mount Lougheed, the last unclimbed north face in the Bow Valley at the time. Like many alpine rock climbs on loose limestone, the grade often betrays the true experience of the route.

On the first attempt of The Warrior that July, Jeff Marshall, Steve DeMaio and Brian Wallace climbed hundreds of metres of shattered rock on Mount Lougheed’s immense north face. High on the wall, Wallace climbed well above the belay without placing a bolt or piton for protection. He slipped off the crumbling rock, fell 25 metres and suffered a fatal head injury at the end of his rope. Marshall and DeMaio endured a truly epic descent; rappelling and down soloing the same shattered stone in a mounting blizzard. After Marshall established General Pain on Mount Yamnuska with Genereux later that fall, he was invited to join them on the wall for a second attempt. “They had a score to settle so I took Brian’s spot,” Genereux says. He inherited Wallace’s pitches, including the fatal lead high on the wall. Genereux traversed further right than Wallace had and into a loose corner. He drilled a bolt and climbed the steep ground, equalizing five pitons higher up to create a semblance of security. The team gingerly climbed the remnants of their new route as part of a profound and terrifying grieving process. “I was there to support [my friends] through this mental hurdle,” Genereux says. “[But] I recommend that no one ever try the route unless they have a death wish.”

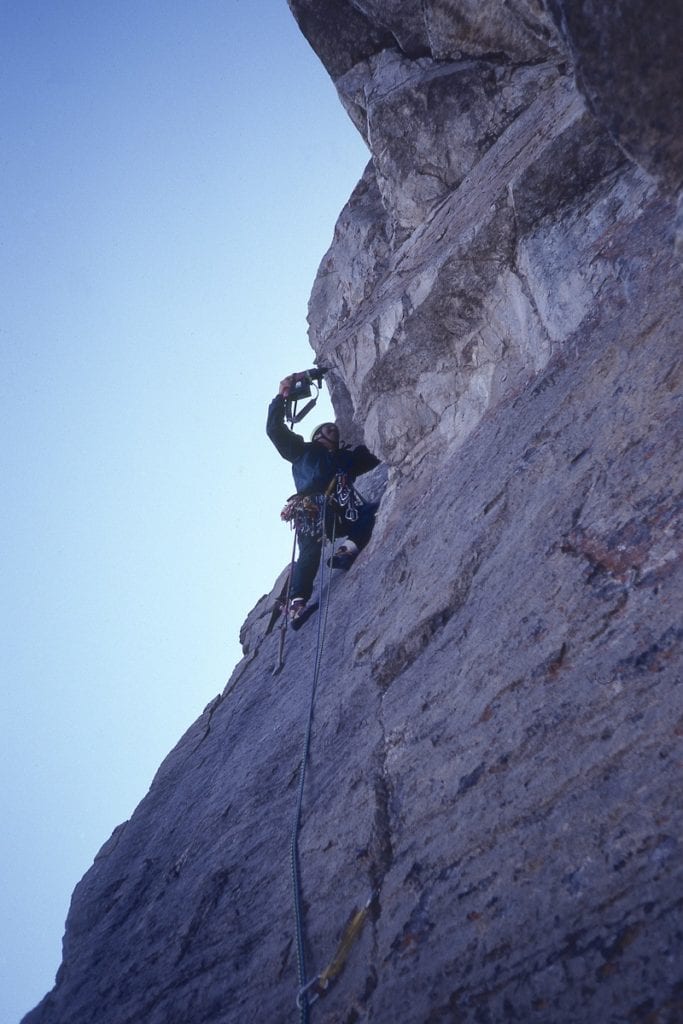

Following 1988’s autumn alpine bender, Genereux continued to feel inspired by big Rockies routes albeit with a different perspective than before. He frequently climbed hard 5.11 on big, loose faces and became enamoured with the idea of free climbing on solid rock — or at least with solid protection. With this new outlook, Genereux pushed a novel practice at the time: carrying a power drill on lead to ensure solid yet sparse protection on his first ascents. To be clear, Genereux’s new routes in the early 90s were not grid-bolted clip-ups. He frequently climbed crux sections from start to finish before pausing at a stance to place a merciful bolt.

Genereux cites Southern Exposure 5.11a/b 300m in the Ghost River Valley as the first multi pitch in the Rockies established in this ground-up bolting style. On the first ascent with Tim Pochay in 1993, Genereux balanced through the technical and steep crux before placing a hook to drill. But the hook popped off its limestone edge and Genereux fell 15 metres, soaring past the steep wall to the base of the crux sequence once again. He latched back onto the rock and repeated the pitch, this time locking off on a crimp to drill his bolt. Genereux and Pochay finished the route and left the four-metre runout through the crux in place.

While subsequent parties have asked Genereux to add more bolts, he believes the spaced yet safe protection is a part of the experience. “You’ve just got to climb the route,” he says. “That’s what I had to do.” Sympathy-seeking climbers will find none from Genereux. And be warned, as the Ghost’s guidebook author, Genereux includes “R” ratings only for routes which exceed 10-metre runouts — a common occurrence while repeating climbs from the previous century. Established with a power drill or not, repeating a route from this era will certainly ensure a memorable experience.

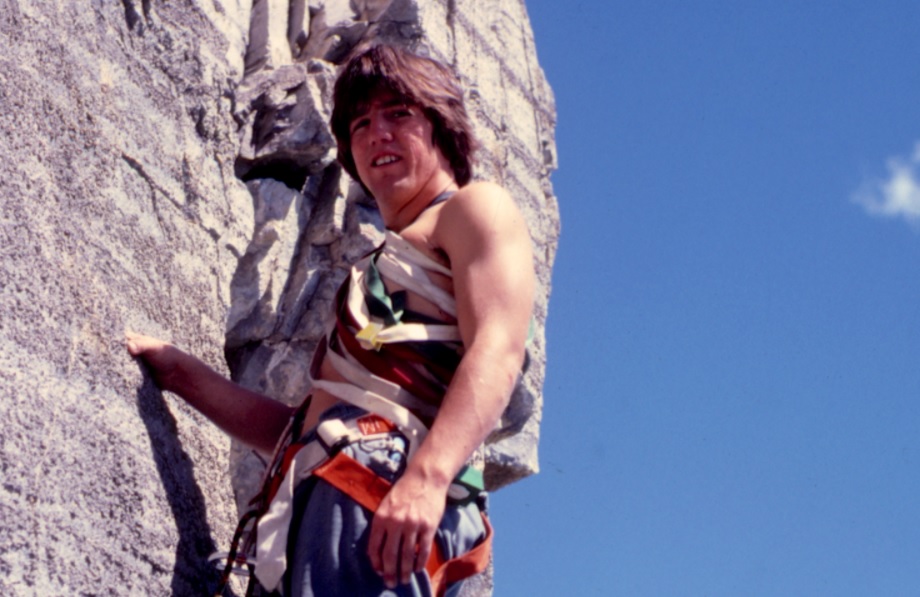

Genereux continued to carry a power drill to quickly establish new routes on lead and grew wary of drilling from hooks. The last straw came on the Ripple Wall in the Rockies when another hook popped and sent Genereux for a 20-metre fall. Chris Kalous, a visiting Coloradan climber and the author of several hard multi pitches in the Ghost, notes that the friable limestone isn’t entirely to blame. “Let’s face it — Andy has 60 pounds on me. For him, hooking was a different prospect,” he says. Genereux concedes this is also where the moniker “the Bumblebee” stems. “Bees, mathematically, shouldn’t be able to fly. But they do,” he explains. “I shouldn’t be able to climb, but I can.” At 5’8” and 200 pounds Genereux describes himself as stocky, yet he has climbed 5.12 in the Rockies for longer than just about anyone. He plays with this nickname in good spirits, like when naming Beeline 5.10d at the Silver Tongued Devil crag. At an area with primarily closely spaced protection, Genereux drilled a scant 11 bolts in 85 metres to prove that bees can indeed fly.

The “Bumblebee” is also a reference to Genereux’s inexhaustible work ethic. By the time Kalous first met him in the Ghost in the early 2000’s, Genereux had all but perfected his rapid lead bolting technique. By attaching a power drill to a shoulder sling, Kalous learned the “uzi-toting” method of development; climbing efficiently over the solid stone and drilling from free stances. “It’s more like placing gear than normal [route] developing,” Kalous says. And when the terrain proved too difficult or loose for ground-up methods, Genereux intuitively knew where to place his route on rappel.

Kalous had heard stories of this indefatigable Albertan during his first of five summers in the Ghost. Some locals imagined a second Genereux running around the Rockies — that would explain all the route developing, trail building and guidebook writing that persisted year-round. At the start of his second summer in the Ghost, Kalous followed Genereux to the top of the immense Wild West Wall for his first taste of this energy. Kalous rappelled into the final pitch of Premonition 5.12c 165m and tinkered for hours placing the route’s final six bolts. He ascended his fixed line and hiked along the clifftop to help Genereux with a new creation. Kalous leaned over the steep face and saw a sea of perfect, blank limestone. Where the hell is he? Kalous thought to himself. Genereux had already bolted two pitches and was starting a third by the time Kalous finally caught up. “[Genereux] doesn’t futz around thinking ‘where is this bolt supposed to go?’” Kalous says. “He just puts them in with good instinct and it often climbs well.”

Genereux’s arc as a climber followed that of many bold climbers who began to question their motivations for the craft. He still climbs serious routes on occasion, but with less frequency and greater deliberation. “I wanted to come back at the end of the day. I didn’t want to become another statistic out there,” he says. Genereux witnessed many friends push themselves into unforgiving terrain and several didn’t come back alive. That’s why, in part, he helped implement top-down route development tactics when necessary.

“Going ground up on shit rock is detrimental to your health,” he says. He now frequents his local crag, Moose Mountain, where the poor rock is not as conducive to lead bolting. While less dramatic and bold, rappelling in to remove the loose rock is necessary. Underneath it all are some pretty great routes. After 47 years of constant climbing Genereux is less concerned about whether a route is established from the ground or above. He’s more interested in choosing the next multi pitch with technical climbing and a solid partner. “I’ve done this for so long I don’t know what else I would do at this point.”