The True, Unbelievable Story of Speed Climbing Comps

The first recorded climbing competition was a speed climbing event over 2,000 years ago

Speed climbing may not be the most traditional form of competition climbing, but it is certainly the oldest. The first recorded climbing competition was a speed climbing event. It happened in Sogdiana in modern Uzbekistan, in 327 or 328 BCE. The sponsor was Alexander the Great, who “proclaimed that he would give a prize of twelve talents to the first man up, [to the fortress of Sogdan Rock] and of eleven to the second, and ten to the third, and so on to the twelfth, who would receive 300 gold darics.” The field of climbers was 300 deep, but the names of the winners are not recorded.

Speed will comprise one-third of the format of the climbing competitions of in the Tokyo Olympics in 2021. And yet, many climbers in North America and Europe appear to hate the idea of speed climbing. Even top climbers have voiced the idea that the other two events, bouldering and difficulty should comprise the whole format. “It does not constitute climbing because it lacks a problem-solving element,” “speed climbing is kind of artificial,” “a shame, an FU to real climbers,” “abrasive, impractical, ugly.” Some even suggest that it is part of conspiracy between Russian organizers known in the west for little else besides their fondness for speed climbing, television networks that want to broadcast a live event where two climbers race each other up a slightly overhanging 15m wall in few wild, all-out flailing seconds and the International Olympic Commission. As it turns out, the conspiracy theory is based on two facts: speed climbing is exciting and Russians love it, after all, they invented it when they set the groundwork for modern climbing competitions.

The road to modern competition climbing started on the Stolby, weathered syenite domes and cliffs that dot the woods on the bank of the Yenisei River near Krasnoyarsk. The impoverished mining town was cut off from the rest of the climbing world and locals developed their own style of climbing, setting an inevitable precedent in Russian climbing culture. Soon, there were climbing competitions, despite the absence of safety equipment.

The two strongest climbers in Stolby were communist-era brothers Vitaly and Yevgeniy Abalakov. They were the first local climbers to make difficult climbs outside of Krasnoyarsk area and were brought to Moscow to study, Evgeniy as a sculptor, and Vitaly as an engineer. The Abalakovs were serious athletes, who trained hard. The Abalakovs ended up in prison on suspicion of trying to ape western climbing’s values as well as techniques. Under Stalin, Russian climbers had to start from scratch and develop their own approach to climbing.

In 1946, after World War Two, local clubs came up with competitions as a fair way to determine which climbers could attend the vaunted climbing camps in the Caucasus or the Pamirs. The rules, at first, were not universally agreed upon, which was an affront to the communist bureaucratic mentality, and made for unfair competitions. In 1955, with the help of Vitaly Abalakov, the Russian Climbing Federation hit upon the idea of simply seeing who was fastest on a single-pitch rock route. By 1955, these competitions were a common feature of climbing in the USSR.

The system created hard climbers. In 1975, Russian speed climbers Anatoly Nepomnyashchi, Sergei Bershov, Vyacheslav Onishchenko, 39, and Valentin Grakovich, climbed a new route on the north buttress of the southwest peak of Bonanza in the Washington Cascades with American climber Alexis Bertulis. In rubber galoshes lashed to their bare feet, with some titanium pitons and a few single-piece static camming units designed by Abalakov, the Russians mostly simul-climbed the 2,300 ft route without protection, even when the climbing was 5.10, the hardest grade of climbing yet done in an alpine setting.

By 1976, the Russians had their competition system dialed enough to invite visitors to a competition in the Yupshara Gorge near Gagra in the Caucasus. French expert boulderer and alpinist Robert Paragot and German Otto Wiedemann, who had climbed with Italian ace Reinhold Messner, both attended, and were impressed by the quality of the Russian climbing and the atmosphere of the competition. “I would describe this sport [of competition climbing] as something fabulous,” said Wiedemann, “requiring an extremely high level of training.”

Few Soviet climbers had access to climbing outside of the Soviet Union. It was unthinkable unless you became Master of Sport by winning several competitions as well as making alpine ascents. The competition scene flourished on its own, while few western climbers ever thought of taking competitions seriously. Most Soviet climbers were getting an opportunity of a lifetime from the system in place and kept to its spirit and rules.

When the Soviet government fell in 1989, funding for the Soviet climbing system disappeared, and some Masters of Sport quit and told the climbers they were mentoring to do the same. Even after the system fell, the love of speed climbing lived on and even western comps, at Arco and beyond, showed their debt to the Russian comp traditions by including speed events.

Organizers realized that to truly tell who was the fastest, routes had to be standardized. In 2005, the International Federation of Sport Climbing (IFSC) had top French climber Jacky Godoffe set a route specifically designed for speed climbing, using variations on a single hold. The ingenious route he created, which was actually harder to climb slowly than it was to climb quickly, became the standard speed wall.

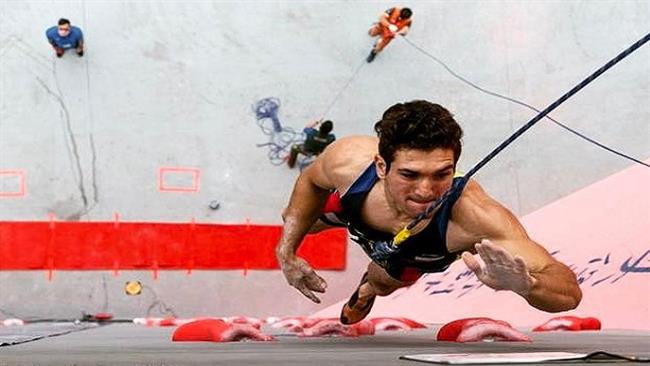

The IFSC then came up with a format for speed climbing competitions that would standardize them internationally. The competition would take place on 15m artificial walls overhanging by five degrees, with autobelays. The clock starts when a climber steps off a pressure plate and ends when they slap the pad from the last hold. The difficulty is about 5.10c.

The top speed climbers are often unknowns in other fields of climbing. Although eastern European countries like Poland, Ukraine and Russian figure heavily in the top five records, countries not typically represented on the podiums of climbing competitions of any kind hold the top two spots: Reza Alipourshenazandifar, the men’s record holder at 5.48 seconds, is an Iranian. Reza, who is self-coached, has earned himself the nickname “The Persian Cheetah,” for his smooth. powerful movement.

Indonesian Aries Susanti Rahayu holds the women’s record at 6.99 seconds. Muslim female climbers have the added disadvantage of wearing the hijab. In Canada, the names of Babette Roy and Brennan Doyle, the highest-ranked national team speed climbers, are not really well-known. Roy is tenth in the bouldering rankings and sixth in lead and Doyle isn’t in the top ten in any other category. Perhaps that’s part of the legacy of speed climbing. It’s a discipline that grew up outside of the mainstream of climbing that requires a different approach and it is hard to predict who will master it.