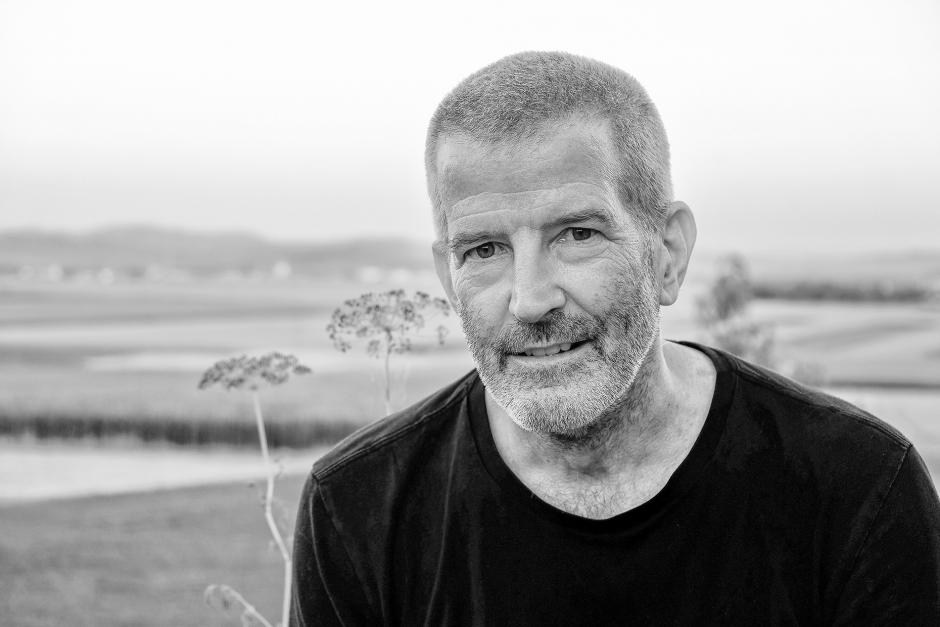

Words with Climbing Legend Mark Twight

Dr. Doom returned to the Banff Centre last fall to talk about death, love and climbing

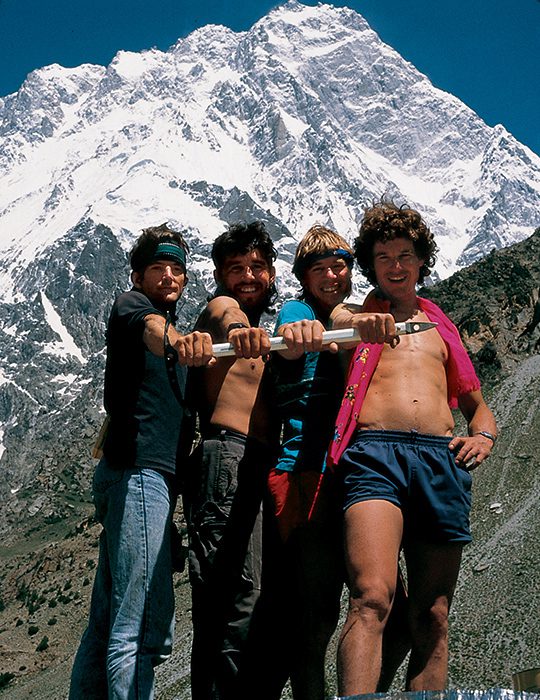

Mark Twight, aka Dr. Doom, was one of the most influential climbers of the 1980s and 1990s. He pushed the limits of winter climbing in the Canadian Rockies year after year. He’s climbed so many dangerous and difficult alpine and ice routes, that he’s regarded as one of the boldest climbers to ever have visited many of the world’s great ranges.

He was one of the first climbers to encourage light and fast single-push climbing and holds one of the Rockies most outrageous speed records. He returned to Banff last fall to speak at the Banff mountain festival about his new book Refuge and the sport of climbing.

What was the last climb you did in Banff?

Honestly, I don’t remember. But the last time I was there and did any climbing would have been 1995 when Bubba [Barry Blanchard] kicked a free-hanging icicle off of Shampoo Planet that hit me pretty hard.

Later we tried a route down in the Kananaskis but were chased off by snow falling on us and more snow rumbling away underneath us. Maybe the last route reached the top of there was one of those Moonrise waterfalls.

You currently hold the speed record for Slipstream, did you think it would stand the test of time?

At the time of that ascent in February 1988, I figured such a record might stand for a few years, especially in light of the speed trip most guys were on in the Alps at the time. Now, in some ways, I wish I hadn’t put the stopwatch on things to the extent that I did. It was driven by ego, which is a useful tool, don’t get me wrong, and a way to communicate competence but unnecessary in the larger scheme of living and dying.

What was the reaction from people after the first ascent of Reality Bath VI WI6X?

I think the general reaction was something like, “He’s suicidal.” That was not untrue but I kept failing at it. The guidebook commentary was probably about right, “so dangerous as to be of little value except to those suicidally inclined,” but that’s also true of Slipstream, Borderline, Polarity, etc., and while I understand the seracs may be less threatening than they were 30 years ago these are still serious routes, not to be undertaken lightly.

Who were some climbing peers that you looked up to when you were younger?

Oddly, some of the men I looked up to when I was starting, namely Jeff Lowe and John Bouchard, became peers and partners later. Some of my earliest influences on a local level were Steve Swenson, Todd Bibler, Jim Nelson, the McNerthney brothers, Doug Klewin and Rob Newsom — all guys who I held in enormous esteem, and learning the lessons I learned from them, implicit and by example, stood me well through my career.

Looking back at your days in Canada, were there any routes that got away?

I would have loved to repeat the north face of Mount Alberta but never considered myself qualified until I wasn’t climbing in the Rockies any longer — and I hate long approaches.

Young alpinists look up to you and your bold routes, any advice for them?

Advice? Yeah, know the stakes and understand completely what you are willing to risk in order to play the game. If it’s just you at risk that’s one thing and only true for a very, very few for a very, very short time in their lives, but when the risk affects others — those in the immediate blast zone as well as those who will only receive the fallout — it is another story altogether and the math never works out. So, get a mountain bike instead, cue a wry wink and an uncurled lip.

What was the motivation behind Refuge?

Long after I quit climbing the void that remained was still present, affecting how I saw, how I spoke, how I lived, and I by the time I started working on Refuge that “lack” remained. Outwardly, one would have surmised great life success and satisfaction, what with the military and movie training, accolades, and all that but the bottom sneaks up on a man sometimes and topples the supports holding up the facade. It became clear in 2014 that I hadn’t dealt with how quitting climbing affected me and I would have to do so if I wanted to live.

How long did the book take you and what does it include?

I formally began working on the book in November of 2016 and finally published in February 2019. The book is basically about coming down, the process of coming down from the mountains to stay down, and to discover meaning in what appeared so trivial when viewed from up there. The first image in the book was shot in April 1985 and the most recent is from 2017, lessons along the way cover the same range of years.

Any books planned after Refuge?

We just published an Anthology of the first five Zines we made from January 2018 to May 2019, which were four issues of Raze — A Fistfight With Human Nature, and a one-off piece titled Collaborate. The Anthology is 196 pages of of unapologetic introspection, featuring a number of contributing artists. Beyond that, anyone’s guess is as good as mine.