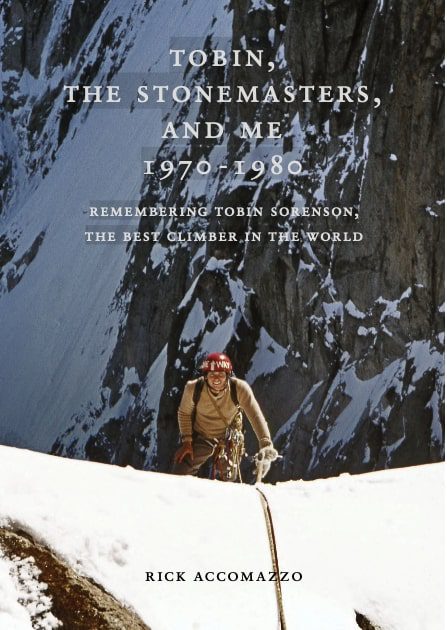

Author Rick Accomazzo: ‘Tobin, the Stonemasters, and Me’

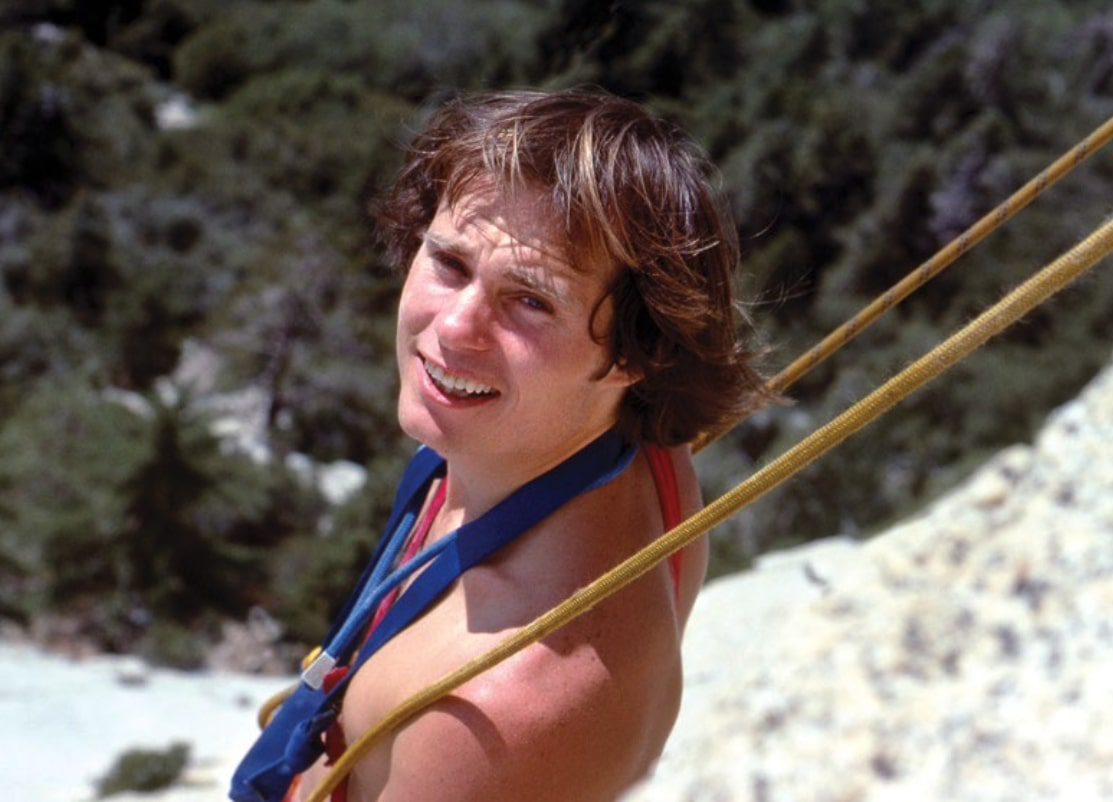

“He was the best all-around climber in the world,” Accomazzo says of Tobin Sorenson in his upcoming book.

Photo by: Photo courtesy Tobin Sorenson Collection

Photo by: Photo courtesy Tobin Sorenson Collection

When Tobin Sorenson died in a fall on October 5, 1980, during an attempt to solo the north face of Mount Alberta, the world lost its finest all-around climber and alpinist of that generation. As the climbing world mourned Sorenson’s death, Rick Accomazzo mourned the loss of a dear friend.

“If he was leading some new route and there was a choice to either go up into dangerous territory, or back down, Tobin would always just go. There was no doubt about it,” Accomazzo tells me from a rainy day at his home in Boulder, Colorado.

In a league of his own—and 45 years ago when gear was more primitive—Sorenson could flash 5.12 trad in Yosemite, excel on big-wall alpine routes, and send hard ice. Some could outclimb him in a single discipline, but none equaled him overall.

In the book’s foreword, fellow Stonemaster John Long writes, “Now, 50 years after our teen-aged days out at Joshua Tree National Monument, his terrifying, hell-for-leather M.O. combined with his Saint Peter deportment, makes Tobin Sorenson the most remarkable person I have ever met. It blew my mind and humbled me way back when, and it still shivers my timbers just thinking about it. It haunts me, too.”

Continues Accomazzo, “Sorenson lived not far from me, about 10 miles away in the suburbs of L.A., but came from a very different background. Tobin was not like everybody else in our group; he grew up as the son of a preacher who led a congregation of about 200 people. Tobin came from that environment, and religion was a big part of his life.”

Accomazzo says, “Because he died at 25, wasn’t a great self-promoter, and didn’t write much about his climbs, I always thought his achievements were underappreciated. And ever since he died, I have wanted to tell Tobin’s story. It took a long time, but I finally accomplished that.”

Accomazzo took ten years to complete his book, part biography and part memoir. Tobin, the Stonemasters, and Me is 357 pages and contains dozens of never-before-seen images of Tobin and others from the 1970s. Three abbreviated chapters previously appeared as articles in Alpinist, but the book has extended versions.

“The book includes my observations and anecdotes about some of the best climbers of the 1970s, folks like John Long, John Bachar, Lynn Hill, Jim Bridwell, and Mike Graham,” adds Accomazzo.

The author started climbing in Southern California at 17 in 1972. He explains that if you wanted to become a Stonemaster, a term the teens coined themselves, you’d have to be able to lead the first climb given the 5.11 rating in the guidebook: the three-pitch Valhalla at Suicide Rock in Southern California. The initial group included Rob Muir, John Long, Mike Graham, Gib Lewis, John Bachar, and Tobin Sorenson, among others.

Throughout the book, Accomazzo shares personal stories about Tobin, including their first meeting at Suicide Rock and their climbing adventures that ranged from Joshua Tree, to Suicide and Tahquitz, to Yosemite and high peaks in several countries. The narrative captures the close-knit nature of the climbing community of the 1970s, emphasizing the social life at campgrounds and the shared passion for climbing that created lasting friendships and indelible memories. He also touches on their varied backgrounds and how climbing united them despite their differences.

Accomazzo’s excerpt from Tobin, the Stonemasters, and Me (1970-1980) : Remembering Tobin Sorenson, the Best Climber in the World is below:

A lucid dream: a full moon, and I am alone, balanced on a slippery granite slab at the top of a towering cliff. Just below my feet, the slab turns vertical and drops thousands of feet. The slope above me radiates a faint moon-glow, but the cliff below is in shadow, black and silent. The vast emptiness at my feet is terrifying, yet I must look down. I am scanning, squinting, searching to find someone, but it’s too dark. Then a great roar, and the entire face detonates into incandescent light. Perfect clarity now: I can pick out where he must be, but it is far, far down the great wall. There is a brilliant orb that is the source of the light, and it accelerates across the night sky: a sun’s passage, but this sun goes the wrong way, from west to east, tracking a day in just a few seconds; it creates a precise, charcoal outline of my standing form projected onto the grainy slab in front of me, but the shadow is racing impossibly from right to left. Then the sun goes out—as if someone threw a switch—and it is gone as fast as it came: darkness again, even darker now since my eyes can’t adjust. The roar lessens, fades, and all is quiet again.

The Interview

How did you first meet Tobin Sorenson, and what was your relationship like?

The first time I saw him, he was up in a tree at Suicide Rock, and John Long and I walked by the base, and we thought, who is this goofy guy? He looked younger than me, but we were born the same year.

Later that day, he did Valhalla, and we all started climbing together at Tahquitz, Suicide, and Joshua Tree. We always camped together in Hidden Valley campground [in Joshua Tree] and had fun times there at night, filling the non-climbing hours with various diversions, such as midnight scrambles to caves and alcoves known as “Space Stations.” Teaching ourselves to climb and hanging out together at campgrounds brought us together as a group and Tobin became one of my best friends and climbing buddies.”

What challenges did you face while gathering information and anecdotes about Tobin and the Stonemasters?

I had to track down his climbing partners, now scattered around the world. For example, Tobin teamed up with the Scottish ice climber Gordon Smith in the Alps and together they did perhaps Tobin’s greatest first ascent; it is on the north face of the Grandes Jorasses near Chamonix and is called Scala di Seta. I didn’t realize until much later all that he had accomplished in that 1977 season in the Alps. As I interviewed these climbing partners, I assembled his record in the Alps where he climbed four out of the fabled, six great north faces, including two new routes, (Dru and Grand Jorasses) a first alpine-style ascent (Eiger) and a winter free solo (Matterhorn). That’s when Tobin’s career really took off. He then travelled to Peru and free soloed a 21,000-foot peak in 1978. In 1979, he went to Australia and raised the existing rock standards by two grades. It dawned on me: who else could do this sort of stuff? Who could climb a high altitude peak—free solo, a partial new route on a 21,000 ft peak in the Andes—come back to the states to do the hardest rock routes, and then pull off technical alpine, first winter ascents in the Canadian Rockies?

How did you decide on the structure and content of the book? Were there any stories or details that were particularly difficult to include or leave out?

The book is organized geographically with chapters on Joshua Tree, Tahquitz, Yosemite, the Canadian Rockies, the Alps, Peru, Australia, New Zealand, etc. Writing about his final year was tough, as it describes how he fell in love and was engaged to be married, before his fateful decision to solo one more hard route, Mount Alberta’s North Face. Describing his death, based on the rescue team’s account, was particularly difficult, as was trying to convey to the reader the terrible impact on his fiancée, family, and friends. I hope that the reader will be able to fully appreciate the audacity and loneliness of attempting a solo climb on the north face of Mount Alberta, one of the world’s most remote peaks, where there was no possibility of help if something went wrong.

What was Tobin’s most significant contribution to the climbing world?

In those last several years between 1977 and 1980, when he died, few could climb rock and alpine at a higher standard, and no one else could climb as well in both styles simultaneously, which was remarkable. Also, the book explains how his 1977 season in the Alps constituted a significant advance in the progression of “fast and light”technical alpinism. When I came to understand all that he had accomplished back then, I changed the title to assert that Tobin was the best climber in the world.

Tobin, the Stonemasters, and Me (1970 -1980); Remembering Tobin Sorenson, the Best Climber in the World is available this July. Published by Stonemaster Books, it is 375 pages, in a larger format packed with dozens of color and black and white photos, and costs USD $46.00. The book can be pre-ordered at the website, Stonemasterbooks.com.