Rock Climbing Gear That Changed the Game

This is the climbing equipment that help the sport grow into what it is today

For thousands of years before the modern sport of climbing, climbers used sticks, spikes and rocks hammered or wedged into cracks, either for progress or for anchoring ropes. As industries like farming, mining, architecture and sailing grew, tools emerged that were later adopted by climbers. When climbing became a sport in its own right, climbers honed these technologies for their purposes.

Tools have been around climbing forever, but a few updates throughout history have really opened up the possibilities of new experiences on the rock and mountains. Here are a few of the biggest

breakthroughs.

Number One: Nylon Rope

Climbers have used ropes for millenia, most of which were madeof hemp and other natural fibres. Hemp didn’t stretch much and had a high impact force on the climber and it was also weaker when wet. Rope breakages due to a climber falling or damage to a hemp rope were not uncommon. When nylon ropes became available in the 1940s, the spectre of rope breakage faded. A climber could fall, with almost no chance of breakage, and the rope stretched to absorb the impact on both belayer and climber. When perlon and nylon kernmantle ropes were introduced, they had the added advantage of stretching less, especially under bodyweight. The nylon rope was probably the single most revolutionary safety innovation in the history of climbing.

Number Two: Carabiners

Before carabiners, ropes had to be untied and threaded through pitons, or tied to them with slings, so that there was rope-on-rope friction in the case of a fall. Carabiners allowed the rope to safely be used with pitons and other gear for running belays, rappels, and more. Ropes either had to be untied and threaded through piton rings or attached with a sling that caused rope-on-rope friction that could cut the rope in the case of a fall. The first carabiners were adapted from mining, construction sites or emergency workers. By the middle of the twentieth century, purpose-built models were available that were strong enough to catch long falls. In the 1940s, lighter, aluminum models were made. In the 1980s, the modern bent gate models became available. Now they are usually seen as components of the ubiquitous quickdraw or screwlocks for belaying.

Number Three: Climbing Harnesses

For centuries, the main means of attaching a rope to a climber was simply to loop it around the waist and tie it. Although many survived long falls with this arrangement, it could damage the spine and the internal organs, flip the climber upside down easily. Climbing harnesses, first by Dolomites ace Jeanne Immink in the early twentieth century, were, however, slow to catch on. In 1970, however, the British company Troll introduced a sewn nylon seat harness designed by Don Whillans. “Since I first tied in as a 16-year old wannabe Odysseus,” writes Yosemite legend John Long, “hell bent on great adventures, ropes have gotten lighter and stronger (thinner, too!); sticky rubber boots have significantly improved performance; camming devices have revolutionized the art of protection; and climbing gyms have normalized levels of difficulty previously achieved only by the few. But questionably, nothing has been so radically undated as the modern climbing harness.”

Back in the early 1970s, some old timers still tied directly into the rope with a climber’s bowline. Not unlike lassoing a wild ass. Falls could leave you with heinous purple lesions about the midriff, so most duffers followed the crowd and switched over to “swami belts,” consisting of five or six wraps of one-inch tubular webbing secured with a water knot. Plenty strong, but wall climbing with a waist tie-in killed your vitals and hurt like hell (all that hanging and jugging), so most of us added crude leg-loops, fashioned from a single loop of one inch web. Sew leg loops appeared in the early 70s, and when combined with the new two-inch tubular webbing swami’s, we had a comfy, if bulky, system that remained popular for another half-dozen years.

The Whillans harness, a British import, was to my knowledge the first one-piece tie-in system featuring leg loops and a waist strap/buckle. I remember test driving one on the Leaning Tower, one of my first wall climbs. The Whillans article was stiff and uncomfortable and had a grievous vertical strap that ran over a male’s package, causing fear and anguish. The fact that this crude, cumbersome unit eventually led to the modern harness is a testament to the creativity and resourcefulness of gear manufacturers. Arc’teryx has taken the modern design and added minimalist design features producing, in my opinion, a work of functional art. But whatever the model, a modern sport harness is remarkably functional and form fitting, and so light you’re rarely aware of even wearing one. The fundamental act of ascent hasn’t much changed in a century, but look at an old climbing rag from the 60s or 70s, when a climber’s tie-in resembled a plastic zip-tie, and give thanks on how far we have come.”

Number Four: The Belay Plate

Belaying the leader, until 1969, relied on wrapping the rope around the body for extra friction. Needless to say, this method was both dangerous to the leader, and the belayer, who could be badly burned by the rope. The introduction of the Munter hitch removed some of these dangers but badly kinked the rope. In 1969, Salewa brought the slotted belay plate to market, a device that easy added enough friction to stop a falling climber. Double-slot models were also useful for rappelling.

Number Five: Assisted Braking Belay Devices

The disadvantage of the belay plate device, however, was that it did little to assist the belayer in their job. The hunt for the assisted braking device, that would lock the rope in the case of a fall, or even sudden weighting, resulted in a number of designs, but none that became as ubiquitous as Petzl’s Grigri, introduced in 1991. The device became so integral to sport and indoor climbing culture that millions of climbers never learned to belay with anything else.

Number Six: The Spring Loaded Camming Device

The clean climbing revolution that started in the United Kingdom, where climbers used railway nuts and pebbles lodged in cracks for protection. Even after a number of commercial hardware companies improved the design of metal nuts, however, they had an Achilles’ heel. Fitting them into absolutely parallel-sided cracks, even when they were designed for camming action was extremely difficult. Camming units have a long and complicated history, but when Wild Country introduced the Friend, the first commercially available, four cam spring loaded camming device, in 1978, they revolutionized crack climbing. Some of the hardest cracks to protect became the easiest. And it wasn’t just cracks. Small slots that would not afford secure nut placements now could be protected with creatively placed SLCDs.

“Cams not only took the clean climbing movement to a whole new level,” writes Black Diamond engineer, Kolin Powick, “by providing another tool that would NOT permanently damage rock with the repeated use of pitons; but also made it possible to protect cracks that were previously challenging to protect such as horizontals and parallel splitters.”

Number Seven: The Modern Climbing Wall

In 1983, French climber François Savigny developed holds moulded from plastic with a bolt hole in the centre so that they could be removed and replaced to provide an almost infinite variety of new climbs, solving the great weakness of fixed feature climbing walls. Climbing walls became infinitely changing kaleidoscopes of climbs. The combination of variety and simplicity of construction led to an explosion of climbing gyms in Europe. Indoor climbing gyms made climbing more accessible by putting them in an urban setting where anyone who could climb for the price of a movie ticket.

Number Eight: The Bouldering Pad

The space between where a rope was wanted or needed and what was considered mere bouldering has always been negotiable. From Yosemite to Fontainebleau, mats padded with a range of materials and old carpets and mattresses, or in the words of Yosemite pioneer Werner Braun, the spotter were used to soften falls. In the early 1990s, however, John Verm Sherman, Greg Burns and other Hueco Tanks bouldering regulars designed some of the first portable, reusable folding crash pads or bouldering mats. With both hinge and taco folding styles available and more padding available by stacking pads, countless problems became safer and some free solos became highball boulder problems.

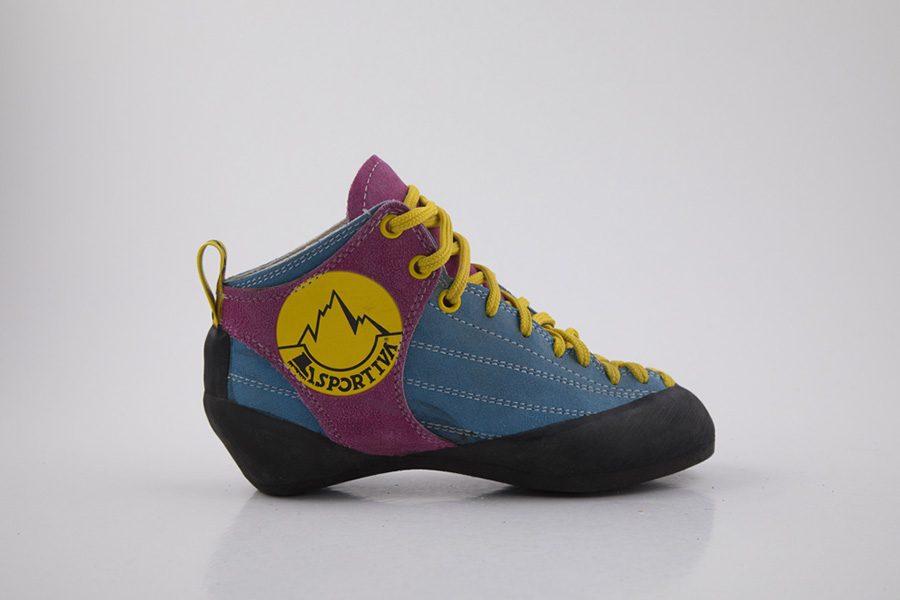

Number Nine: Sticky Rubber and Modern Climbing Shoes

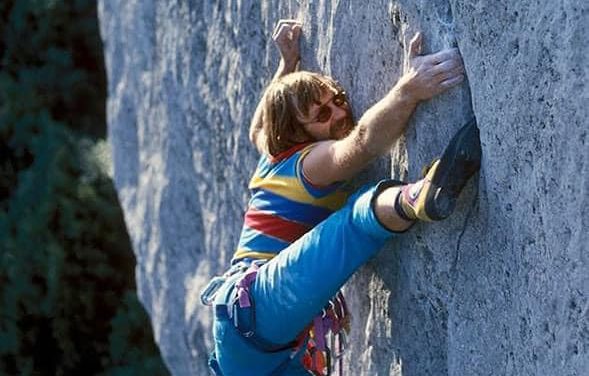

For most of the history of rubber-soled climbing shoes, bulk sourced rubber or rubber designed for maximum durability was used on rock climbing shoes. The results were often shoes that lasted a long time but didn’t stick to the rock very well. In the late `1970s, the Boreal company in Spain bought one of the first scientific programs to improve the rubber on rock climbing shoes. The result was rubber so sticky that they sold shoes by rubbing the soles together until they stuck together. The stiff, board-lasted Fire was the first sticky shoe model, and took the climbing world by storm, but when soft, sensitive slip-lasted shoes were paired with the sticky rubber a couple of years later, the stage was set for a revolution of footwork and hard climbing. “Sticky rubber made a big difference for me,” wrote Austrian shoe designer Heinz Mariacher – seen in the featured photo above in Arco in 1983.

“Having confidence in my feet on less than vertical routes was crucial when risking runouts (especially when exploring new routes ground up. As a rock climber I always strongly believed in the importance of sticky rubber, but nowadays I have the impression that most climbers don’t really care. The real revolution has been adding comfort to precision. Modern rock shoes don’t need to be extremely downsized to work. In fact, they work better if not downsized too much (more than one size.)”

Number 10: Portaledges

Single-point suspension hammocks were introduced by Yosemite big waller Warren Harding in the 1960s. These were light and easy to set up but crushed the shoulders so painfully it was extremely hard to sleep. Yosemite big wallers started hauling up camp cots and suspending them from single anchor points. In the early 1980s, the first commercial models were available. They folded, weighed less than camp cots and afforded a comfortable surface for a night’s sleep. In 1986, John Middendorf’s A5 company introduced double models that were lighter and easier to set up. Since then, portaledges have become the standard for wall bivouacs.

Number 11: Leashless Ice Tools

Leashless tools, writes caadian ace Will Gadd, “were born in the fire of the first Ice World Cup and refined in the mixed climbing revolution of the late 90s. Leashes, ‘fruit boots,” spurs, no spurs, this was an era of massive equipment and mentality change in what had seemed a relatively staid sport. The big thing leashes allowed was fast matching on tools to change hands. With your hands manacled into your tools you can’t readily switch hands, and when you’re on overhanging rock changing hands on a tool is often essential. Easy matching and tool switching are also useful for pure ice climbing, but without hard drytooling and mixed climbing pushing the need for ready matching we’d still probably be using leashes on ice. Unleashed, we could do a lot of moves that never would have worked with our hands manacled to our cools with leashes. Rapid switching from figure 4s to 9s, choking up on the grip for more reach (which has also led to a lot of accidents and falls ice climbing), it just works better. Tool design also changed radically during this period, with the Black Diamond Fusion and Petzl Ergo tools leading the way. Wild times!”