Tami Knight Talks Cartoons and Climbing

The legendary rock climber talks about her time in Canada during the 1980s and the start of her iconic comic strips

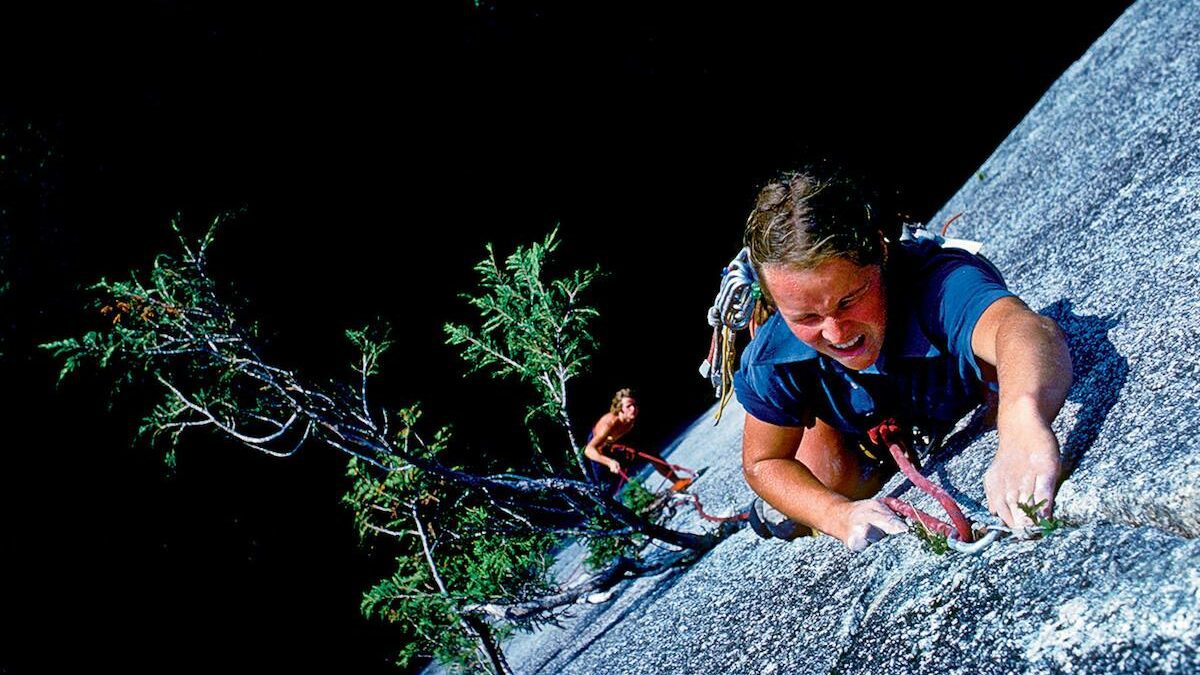

Photo by: Pat Morrow

Photo by: Pat Morrow

At the University of British Columbia (UBS) in the late seventies, Knight was studying agriculture in the hopes of getting into veterinary medicine, when she was involved in a car accident During her recovery, a friend asked her to go climbing at Squamish and he invited her to try the classic Exasperator 5.10c, her first route of that grade. There, she met teenage locals Peter Croft, Randy Atkinson and Richard Suddaby. Knight’s gymnastics background and fearlessness made hard climbing a natural fit. Croft was so impressed watching her that he asked her to climb two pitches of White Lightning, a 5.10c slab. It wasn’t Knight’s first climbing day, but after that, she said, “I just wanted to go climbing, real bad. I went after it like a fish in the water, and when I got a rope, I slept with it. The rope smelled of the outdoors and, even more then that, climbing.”

Knight’s mother had been a research scientist with a master’s degree in zoology and a member of UBC’s Varsity Outdoor Club. Tami grew up listening to stories about BC pioneering alpinist Phyllis Munday and Coast Range mountaineering. Her mother raised her to welcome the challenge of living “in a man’s world.” Both her parents were skiers and athletes, and her mother taught her cartwheels as a kid and signed her up for gymnastics when she was four years old.

Growing up in west Vancouver, Knight was a fanatical gymnast, constantly touring, competing and training. In 1975, she placed 16th in Canada while trying to qualify for the Montréal Olympic games. While she worked on her layout full twist, however, she suffered a fall that gave her a concussion and the twisties. “I lost my place in the air. It eroded my skills and I lost everything. No one understood the twisties, and it seemed like it had only ever happened to me.”

After leaving elite gymnastics, she went climbing with some high school friends. “I had strength and flexibility, loved identifying as something and climbing was a natural progression. My friends had ropes, I had access to a car, I lived an hour from Squamish. Climbing came stinking easy.”

After meeting Croft, the two climbed together every weekend; and they became a couple and a prolific climbing team. Squamish crags saw few climbers and the previous generation had mostly departed the scene. The big plum was the second ascent of Eric Weinstein’s Sentry Box, 5.12a. It was an intensely creative period of climbing and they often made a first ascent every day of a climbing trip. The late 70s and early 80s were a golden age of Squamish free climbing. All this creativity unfurled in a setting where climbing was not well known or even accepted.

“Pubs were biker bars, it was climbers vs. blue collar workers,” recalled Knight. One night, while she and Croft slept in her car at an impromptu camping spot, inebriated locals came and started rocking it, trying to flip it over before they drove away without getting out of the car. The climbing scene itself, she said, was “ratty, dirty, smelly.”

Knight and Croft also climbed in the Bugaboos, the Cascades, the Coast Range, Wales, Scotland and Yosemite. They made fast ascents of long routes, often simul-climbing, and climbed the Northeast Buttress of Mount Slesse, 5.9, car to car in a single day and even had time to reach Vancouver before last call. In Yosemite, they went after the long free routes like Snake Dike, DNB on Middle Cathedral, Northeast buttress of Higher Cathedral, North Face of the Rostrum as well as the first Canadian ascent of Astroman, then the hardest long free route in the world. After climbing Astroman, Knight couldn’t figure out just why the climb had wiped her out so badly until she got home and discovered she had mononucleosis.

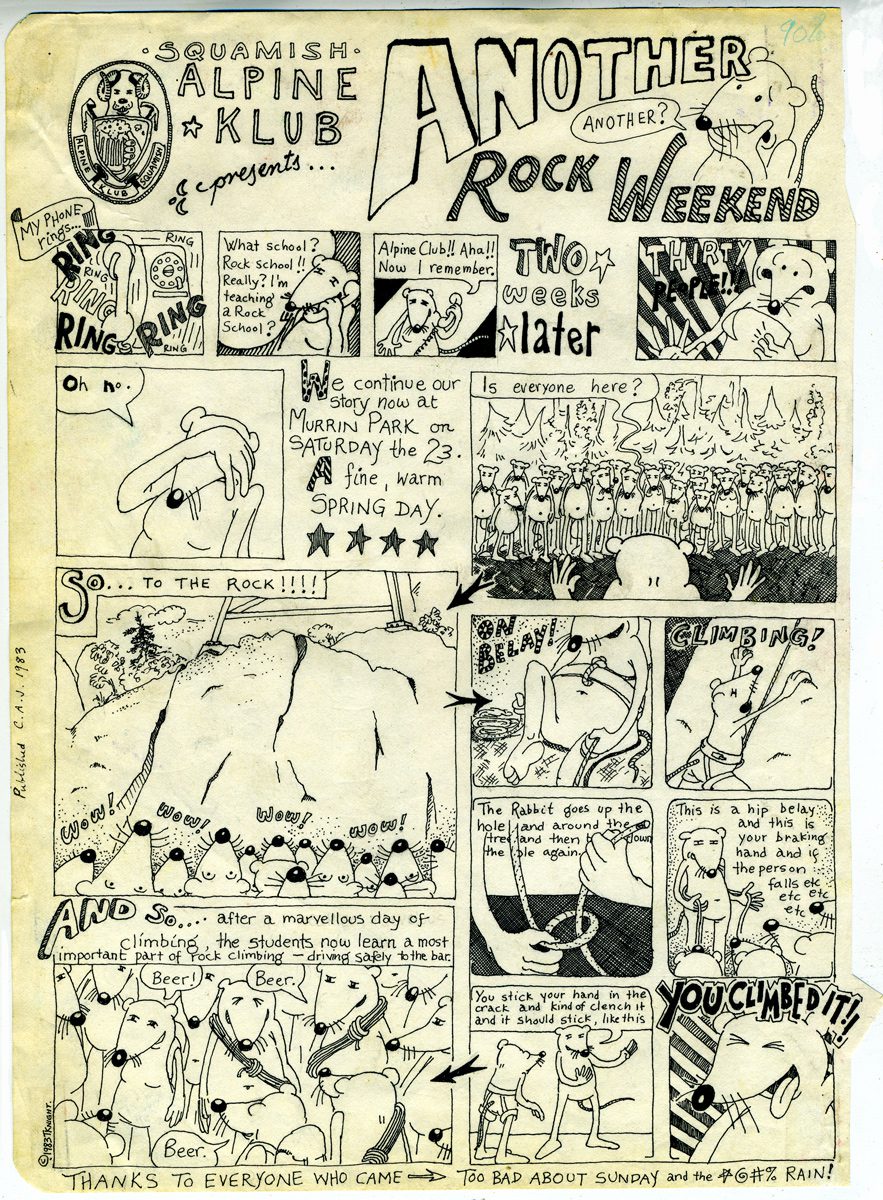

In addition to her own ambitious climbing schedule, Knight also experimented with being a climbing instructor. She led a rock weekend at Squamish, where 30 students signed up. She called a dozen local climbers to come help teach and Murrin Park likely had its busiest day in history to that point. Although she was a natural teacher who would later go on to teach gymnastics and circus arts for almost two decades, it was art that really captured her imagination.

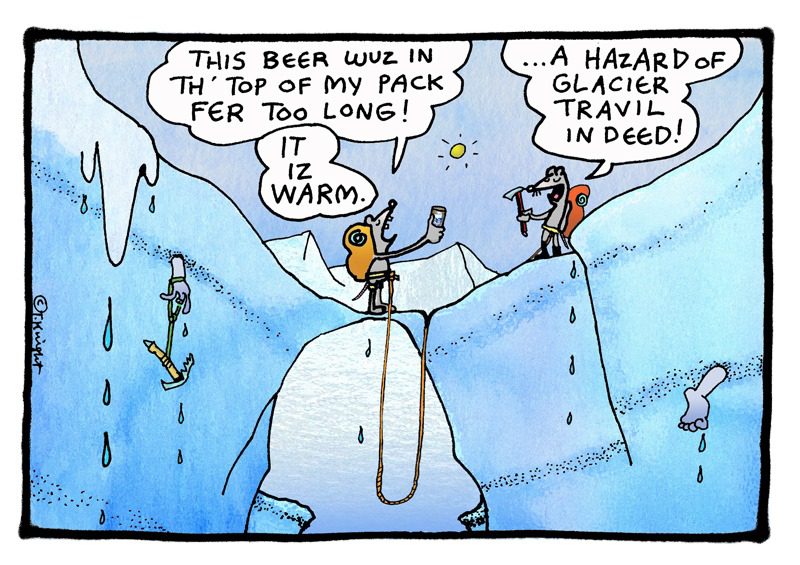

In 1981, Knight started drawing cartoons about the hi-jinx the climbers she knew got up to. Her main influences were Dr. Seuss and Mad magazine. Climbing cartoons, however, went back to the nineteenth century, and had a more recent heyday with the work of American cartoon artist Sheridan Anderson, so in a sense, Knight was reviving a tradition, with an intense focus, at first on the little climbing world of Squamish. Knight loved writing up her climbing adventures and bringing climbing to life through a mix of graphic art and written word intrigued her.

Knight says she “saw things other climbers didn’t see, I saw the absurdity,” but she also saw the fun. Most climbers were amused to see themselves in the cartoons Knight described as “tucked into folds of all of that climbing life.”

One of her first cartoons, “A Squamish Rock Weekend” was published in the Canadian Alpine Journal. The editor at the time was the venerable Moira Irvine, an old school mountaineer and collector of model trains and toy soldiers, who nonetheless was charmed by Knight’s fresh and candid insights into climbing life.

Knight usually portrayed the climbers, mostly based on her friends, as walking, climbing, beer swilling rats. They were ruled by a powerful impulse to do anything to climb and to do it as cheaply as possible. Together, they try to climb, get free gear, learn new skills or react to the climbing issues of the day, from climbing competitions to sport climbing. Knight’s characters’ banter is hilariously but accurately missing syllables and consonants left and right such as “rite on,” “thissiz,” “donchya,” “wanoo.” Her use of “Ya” stands in for both you and yes – as if they were saving the mental energy required for fully-formed speech “fer climbin.”

Climbers were instant fans and passed on the cartoons and their lore through their cultural grapevine. The stories on which some of her cartoons were based were now re-told as part of climbing lore. Climbers even claimed to have invented some of her jokes, notably, “The disposable avalanche poodle.”

The more she drew, the more Knight realized that her real passion was art cartooning, not guiding. Her power to make a mark with art was proven. She went to the Emily Carr College of Art and graduated in 1983. Over the years, enough cartoons to fill six books followed. In 1985, she went tree-planting, broke up with Croft and the following year visited Kenya with fellow climber Jacqui Beaubien.

“Back then,” said Knight, “you could get unemployment insurance after planting.” She expanded her cartoons beyond the little host of characters she had based on her friends, to cover climbers in general. “It was like I was throwing stones through the windows of the church of climbing,” said Knight, “that some saw as a kind of religion.” Inevitably, some climbers did not like her work, but what cartoon could appeal equally to everyone? The role of court jester has its liabilities.

Her parents didn’t like the idea of a life spent only on making money for the next climbing trip, and she didn’t want, in her words to be “stuck in the poverty of the outdoors industry.” She slowed down as a climber, married, had a son Isaac in 1990 and daughter Dominique in 1991. A decade later she was divorced and eventually settled down with her second husband, Phil, who she’s been with twenty years. November 2022, they became grandparents to Felix, the first born of Isaac and his wife.

At 63 years old, Knight no longer climbs and her body can’t keep up with hard climbing anyway. But she still teaches gymnastics and her little students know that “Miss Tami”, as they call her, can always be hit up for “story time” rather than scary skills or hard conditioning.

There is something old-fashioned about Knight. She once worked at a climbing gym as what she calls “a belay cop,” in the early 1990s and experienced gyms as “a bunch of young people sitting around talking about avocado toast,” she didn’t agree with climbing in becoming an Olympic event. But her goal with her cartoons isn’t to turn back the clock, but to remind people of the ridiculousness of the present and the traditions of climbing.

“I want people to be kind,” Knight says, “and listen to people who came before. If they learn from cartoons great, if they had a laugh, yay.”