The North Twin: 10 Years After, by Barry Blanchard and Dave Cheesmond

“There are no continuous crack systems, almost no ledges and it is very steep. We still feel confident about making the climb.” – George Lowe, AAJ 1975

In 1985, Dave Cheesmond and Barry Blanchard made the second ascent of the north face of the North Twin via their route the North Pillar VI 5.10d A2.

The second ascent of the long and dangerous route was in 2013 by Jon Walsh and Josh Wharton. They freed all but the final bulge on the headwall and graded the face 5.11+ A2 VI.

The 1,500-metre wall is one of the most serious walls in America and has only been climbed four times, despite attempts by some of the world’s best alpinists. After their climb in 1985, Blanchad and Cheesmond wrote the following story called 10 Years After.

10 Years After

“The hike up to the Woolley Shoulder is pleasant. Once across the river we find no trace of human trail. The going is good: the forest and stream friendly under an only slightly cloudy sky.” – George Lowe, AAJ 1975

Cheesmond: More than then year after the first route was put up on the north face of the North Twin, Barry and I are walking in on a hot July day to try and find another way up this mind-blowing wall. As we plod on up I question myself on whether things have changed much in the interim. Now there is a hut on the other side of the col, a slight trail makes its way along the creek, one can see some traces of the twenty or thirty parties that go into the northern Columbia Icefields each summer.

But really the experience is the same. This is still a remote mountain and possibly the most serious limestone face in North America. A decade ago the Jones/Lowe route on the face was the hardest climb in the Rockies – it still has not had a second ascent. When George and Chris walked in here they were looking for adventure. They found theirs – we were here to find ours.

“Were we ready for North Twin or were we kidding ourselves?’”– Chris Jones, Ascent 1975/76

Blanchard: Dave is ready. He wants to climb North Twin this year and he knows what he has to do to do it. Lots of long, hard, serious limestone routes all spring. He’s in good shape.

I hope that I’m ready. Too much work guiding this summer and not enough time to climb for myself. But I am fit and my motivation is strong. Ever since I first saw North Twin in 82’ the face has occupied my dreams for days at a time – running and thinking about The Twin, guiding and thinking about The Twin, belaying and thinking about The Twin. As Henry Abrons wrote once, “North Twin acts like a drug on the mind of the observer.”

July 30th, 1985: Today it starts. Dave and I enter that special alternative reality that is alpinism. We leave our glacier camp at first light. The lower section of the face is mixed snow and rock climbing. We make good time moving together with heavy packs slowing us down on the steeper parts. Above us is the first rock band of vertical grey limestong, very compact with straight and clean crack systems. Which one to take? We finally decide on a corner crack that looks drier than most.

After donning his rock shoes, Dave starts up. He is wearing luminescent pink socks for the route – all hes lacking to make this look like a crag climb is candy striped tights and a chalk bag. As if the mountain can read my thoughts it releases a volley of rockfall to remind me that we are on a large Alpine face. The sun catches the upper face for several hours each day the danger from falling rock is extreme. The steepness of the band we are on protects us from direct hits, but I am still scared shitless.

Dave takes a hanging belay when the rope runs out and starts hauling his pack. Due to the steepness the jugging is strenuous and I’m glad to finally get to the belay. How was it? I ask. Five-ten man, he replies. This would be the standard answer for the next four days whenever I question the rating of a pitch. Only the suffix ‘a’ to ‘d’ would change sometimes.

Soon we are up the first band and I take over for the final section to rock that leads up to the lower snowfield. There is less protection from falling rock up here, so we wasted no time moving up ever easier ground to eventually run across the snow to below the next steep rock. Fourth class traversing left leads to the base of the pillar that will be our route for the next few thousand feet. Dave leads a pitch up the pillar, I run out the rope once more and its time to bivi.

“We dig a nice platform for our bivi tent on the edge of the bergshrund. After a hot stew for dinner, sleep comes easily on flat ground. During the night only a few pebbles dribble onto the top of the tent to remind us that we are on a mountain wall.’” –George Lowe, AAJ 1975

Cheesmond: Our first night on the face is spent level with the hanging glacier in the centre of the face to our left. Brewing up we discuss the incredible coincidence that has another party on the Lowe/Jones routes at the same time as we are trying our new one. All day we have been able to shout across and hear answering calls. It makes a pleasant change from the constant hum and whir of falling rocks.

During the night we are treated to a regular symphony of crashing ice as the seracs on Mount Stutfield calve. Each time I wake in a sweat thinking the mountain is collapsing on top of us.

In the morning Barry exclaims at seeing a small tent on the glacier below. This is too much – a third party in here, when the face usually sees no one in years. Eventually we figure that it’s our unknown friends from a few thousand feet away across the face. They must have found the rockfall too unnerving – hopefully they weren’t hit. With sadness we watch them pick their way through the debris and crevasses on the glacier. It seems we knew them intimately after only a few long distance shouts.

“There are no continuous crack systems, almost no ledges and it is very steep. We still feel confident about making the climb.” – George Lowe, AAJ 1975

Blanchard: Today, July 31, the weather is clear and warm. One lead up moderate cracks puts us onto a ledge cutting across the pillar. The ledges seem to be all composed of shale, and finding belays is difficult. Dave takes the next pitch to a better belay. It’s my turn to put on the rock shoes. I have no problem fitting my size eight-feet into Dave’s size 10 boots. The climbing is steep. Thirty-feet out I make a pull up onto small face holds. There’s a loud snap and my left hand is off. Managing to grab the nearest sling I am able to find hods for my feet, but kick a baseball size rock into space. The rock sails out and freefalls directly onto Dave’s thigh, stretched out for balance while belaying. Damn. Dave curses with pain and rubs his leg vigorously. What happened? I look at my left hand and the ring finger is swollen and sprained. I must have cranked to hard on the small holds. After the climb Jill, my wife, told me it was just an excuse to get out of weather my wedding ring. At the time I wonder if it isn’t just an excuse to get out of leading.

After lowering me to the belay and some more rubbing of his thigh, Dave puts on the shoes and finishes the lead. Above we continue up difficult steep pitches. Dave is going like a machine. The last lead up the middle band is a solid, steep to overhanging hand crack. Another one that was “Five ten, man.”

Above I traversed left to an ice screw placed at the bottom of the second ice field. Already it’s late, and after filling a stuff sac with ice we rap to a protected ledge. As everything is sloping we spend the last of the daylight building platforms out of flat rocks, before starting the familiar brewing routine followed by sleep.

Cheesmond: We start our third day on the wall with crampons on and the headwall looming malevolently above. Barry is always impressive when climbing ice. Whether its leading a grade six water fall, using French side stepping high in the Karakorum, or climbing together on a sixty-degree slope like now, he exudes confidence. Growing up in Canada where cold, snow, and ice are a way of life, he has become totally at one with his medium and a perfect master of his craft. I can think of no one person safer to have above when rushing up a potentially hazardous ice slope.

I appreciate all of this when he drags me safely up the ice and into the shelter of the buttress at the base of the headwall. Changing once again into rock shoes and discarding my pack I start up. Initially there are inside corners with some of the best jam cracks I’ve yet seen on limestone, thereafter a key traverse pitch led by Barry in his big boots. This puts us at the base of the main crack system in the headwall. While jugging I can look ahead and see that the next three hundred feet at least will go.

Soon I’m struggling up an off width that would look terrifying even in Yosemite. Why didn’t we bring the #4 Friend along? Thirty-feet out from a poor pin I hang out and wonder what I’m up to doing this sort of thing here. After a lot of frigging around I finally manage to reach into the back and lasso a chockstone. Using this for tension I am able to swing across to a finger crack in the right wall and thus get up the pitch. Two more pitches up the break land us on a tiny ledge in the middle of nowhere. When Bubba gets to me he asks whether I have any ideas of how to chap a bivi ledge in sold rock. As it is starting to get dark I see his point.

Sometimes in the bleakest of situation the mountain gods look down on our puny struggles and take pity. This was just such an occasion as I look fifty-feet diagonally up and notices a small hole in the face. Half-an-hour later we are chopping the ice off the floor of a perfect two-man bivi cave. With the stove hanging in a pin banged into the roof, we feel satisfied with ourselves and pleased of the break we have been given in the middle of this vast area of vertical rock. Dozing off that night we seem totally secure, and for the first time since starting on the face can untie from the rope. The absolutely best bivi cave in the world.

“Suddenly the rope jerked upward. ‘God, he’s of,’ I thought as I grabbed for the belay rope. In a flash I saw the last piton pull, saw the tremendous wrench on the remaining belay anchors. Then all was quiet.” – Chris Jones, Ascent 1975/76

Cheesmond: The fourth day on the face turns out to be eventful. First the feeling of impending doom on leaving the security of the cave and then the continuous difficulty and seriousness of the climbing. About two rope lengths up from the cave I’m relaxing in my butt bag while Barry jumars. Suddenly I hear a crash and find myself three-feet lower down with the jug line pulling on my waist. There’s also an intense pain in my left shoulder. After what seems like a long time Barry transfers his weight to a point and in between spasms of pain can move back up to see what happened. Dangling uselessly from the crack is the nut that was the main belay; the chockstone that was backing it up is gone. The fracture in the side of the crack tells its own story, the slab that came away hitting me as it started down on the way to the glacier. Luckily, the back-up pin and wire-nut held, which stopped us from following the slab for a ride.

Somewhat shaken I place all the gear I have and tie it all together for psychological reassurance. For the rest of the day we both are haunted by blocks that move and cracks that expand.

Blanchard: I’m belaying Dave on the pitch above our failing anchor fiasco. Over to the left water is falling off the face in a fantastic display as sunlight explodes the drops into brilliant jewels. The drops start from the lip of the headwall and by the time they pass me they are two hundred feet out from the wall. As so often happens when I climb, songs are going through my head. I’ve done routes to Warren Zevon, Emmy Lou Harris, even The Clash. This time it’s Stan Rogers and as I wail out the chorus of Northwest Passage I hope it gives Dave energy. I imagine ourselves as modern day explorers:

“Ah, for just one time I would take the Northwest Passage

To find the hand of Franklin reaching the Beaufort Seas

Tracing one warm line through a land so wild and savage

And make a Northwest Passage to the sea.”

“Our pace is becoming worrisome. We spend the night locked into our own concerns on separated ledges.” – George Lowe, AAJ 1975

Blanchard: Aug. 3. Today is day five and we’re out of food as of now. Things have been going according to plan, but we have to get off soon. It’s not hard to leave our slim bivi. I’ve spent the entire night trying to wedge my left cheek into a crack, my feet suspended in a sling and a light drizzle making my bag wet. Dave admits he hasn’t slept much either, for fear of falling off.

One pitch takes us to a good ledge beside a detached pinnacle. This flake is the last feature that we could make out when studying the face with binoculars from the meadows. The big question remains – is there a way out of here?

Dave disappears around a corner to the right. Slowly the rope goes out. I wait anxiously when he warns me he is about to come off, but finally the last few feet are paid out. A burst of yips, yaps and yahoos let me know he is off the headwall.

As I jumar, a foray of rockfall scares me breathless. Ah, man, not now when we’re so close. I reach the belay stern faced and nervous. How was it? I ask. Not too bad, he replies, but I sense we are both relieved to be at last onto relatively easy ground.

I lead two quick pitches up shallow and loose rock, Dave follows on towards the ridge. As he hacks ice off the rock the mist makes a surrealistic scene of the surroundings. Dave’s yellow jacket seems to glow, a sundog surrounds him, and every time his axe strikes the slope a shower of ice crystals fan out into the beams of sunlight breaking through the cloud. It looks like a starburst, the sight is incredible, it’s wild. Dave is there, the apex of the ridge, the face is behind us. I scream out with joy.

Getting to the summit is an Alpine route in itself. Several pitches of fifty-degree ice and some fourth classing take us to a step in the ridge. An intimidating corner provides our passage. Abrons and friends must have first climbed this section when they did the northwest ridge twenty years ago. I feel as if I know all these people who have come this way before.

Collecting drips from rocks near the summit, I have time to rest and appreciate this route and my friend with whom I shared it. The climb has been totally awesome. And Dave has climbed with genius. I’m a lucky man to have both.

“As we reach the top of the band the storm, unnoticed in our concentration on getting up the band, breaks and it begins to snow heavily.” – George Lowe, AAJ 1975

Cheesmond: Plodding across the icefield in a bitterly cold wind I can look back on our climb and be grateful we had no mishaps. Rescue or any assistance would be virtually impossible on such a face and in the event of bad weather there is no easy escape route. The consequences of an injury from a fall on the headwall would be serious to say the least. We still have another hungry, storm-bound bivouac ahead of us, the crevassed summit of Stutfield to cross and a complex icefall to negotiate on our way back to safety. This is not the sort of route to attempt without being both physically and mentally prepared for one of the biggest and most serious of Alpine faces.

Will it also still be awaiting a second ascent 10 years hence?

“There was a clear sense that it had some meaning for a future generation, but what it was I could not say.” – Chris Jones, Ascent 1975/76

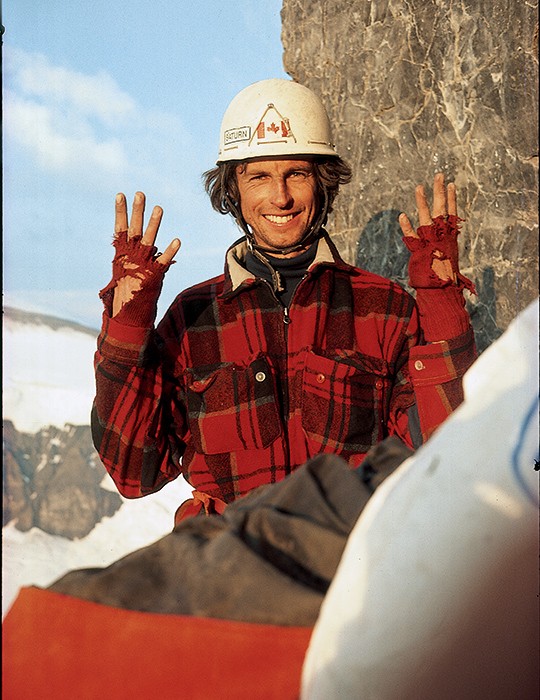

– Barry Blanchard currently lives in Canmore, Alberta, where he works as a mountain guide. Dave Cheesmond died in 1987 on a climbing expedition with Catherine Freer to the Hummingbird Ridge on Mount Logan.