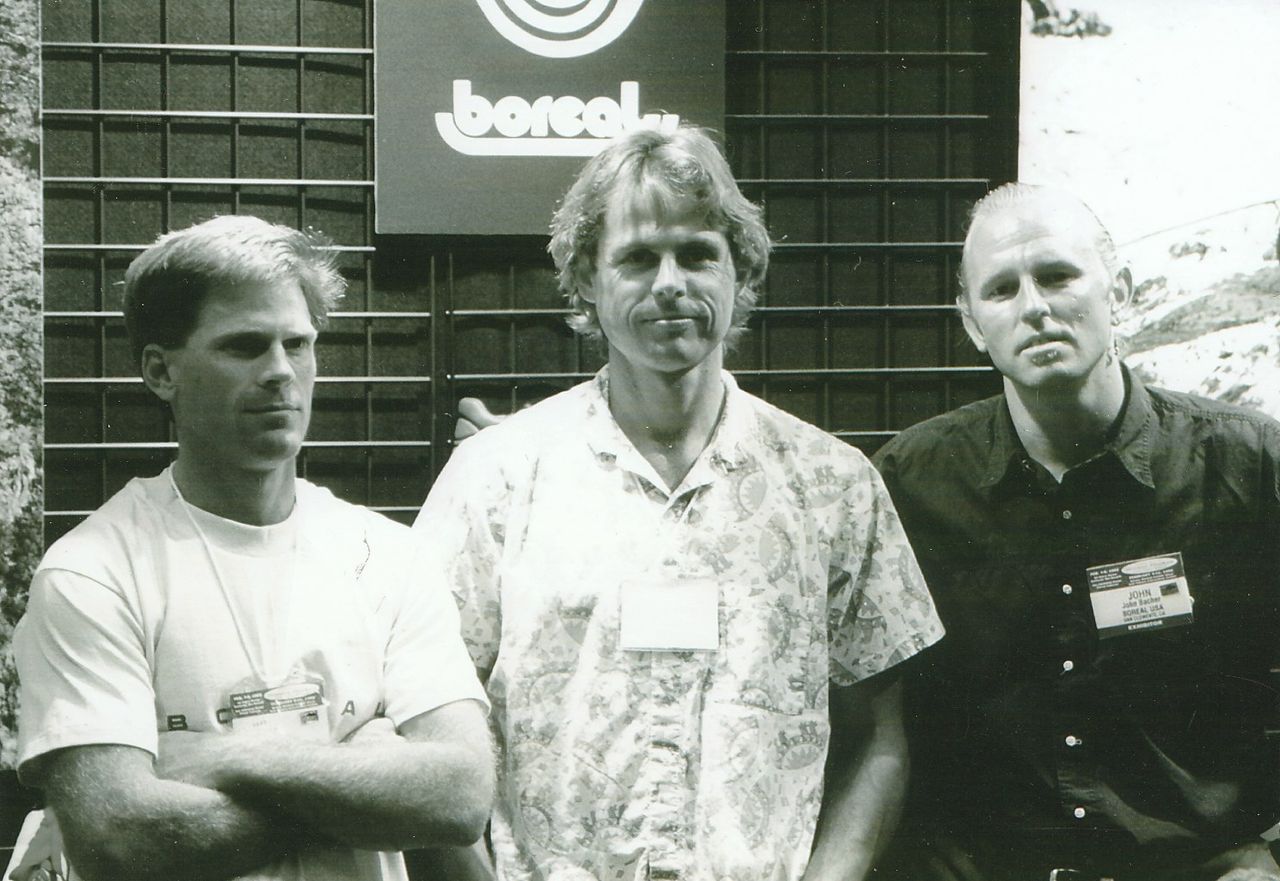

Yosemite Climbing Legends: John Bachar

From cutting-edge free-solos to opening now-classic hard cracks, John Bachar was one of the best rock climbers of his generation

John Bachar was born in 1957, the year when the Golden Age of Yosemite began with the first ascent of the Northwest Face of Half Dome, but he would go on to lead his own epoch in the history of American climbing, the age of the Stonemasters.

Bachar’s father was a math prof at UCLA and a baseball fanatic. Bachar was a natural student and highly competitive in baseball, where he played the position of short-stop with a ferocious refusal to yielded a single inch that impressed even his father, a self-professed competitive spirit.

After his parents divorced, Bachar started visiting the Los Angeles bouldering scene’s shrine of the sandstone crags and boulders of Stoney Point. There he ran into Bob Kamps, who had first come to the area in the late fifties and become a legend of American rock climbing.

He started trying to emulate Kamps’s moves and was even more impressed when, on his first visit to Tahquitz Rock he repeated Kamps’s and Mark Powells’s route Chingadera, one of the first 5.11’s in California. When Bachar said the route was “horrendous,” he meant it as a compliment.

He started skipping school to climb, scaling anything from backyard trees to shopping malls and picked up his first climbing book, Royal Robbins’s Basic Rockcraft. The ethics section made a strong impression. He developed a dislike of bolts, as something that takes away from the rock, accepting them only sparingly, and only when placed on lead. Bouldering and climbing unroped remained the supreme expression of climbing for him.

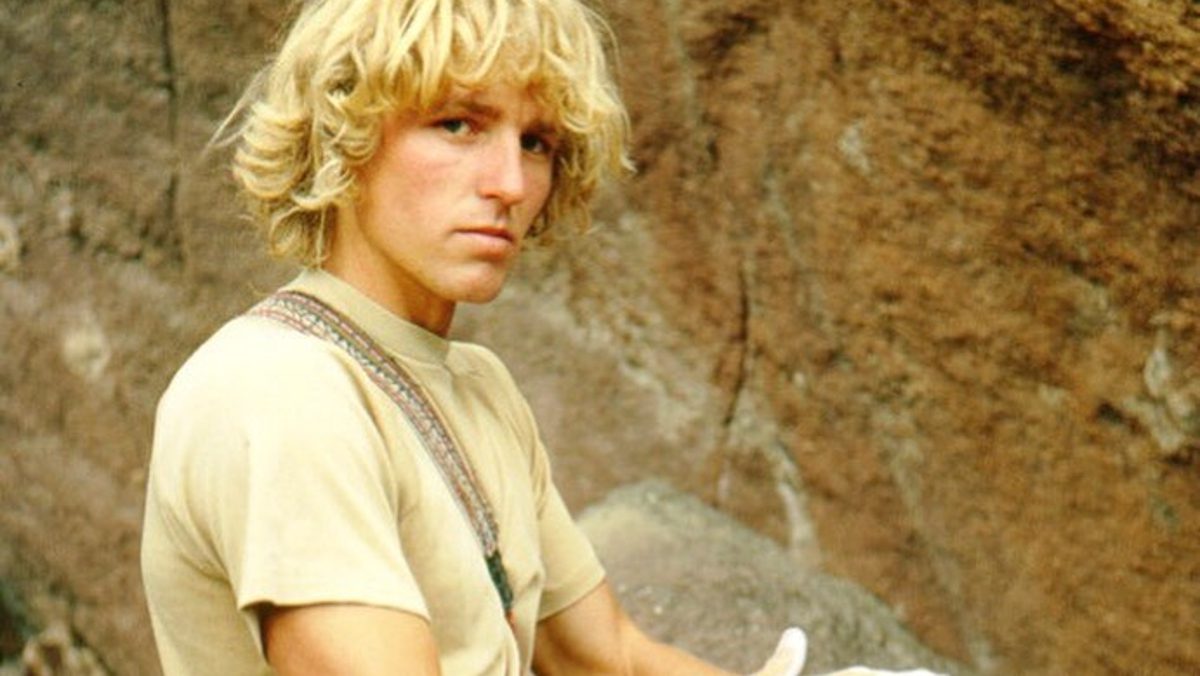

Bachar made a series of hard first ascents in Joshua Tree, Tahquitz and Suicide Rock. His partners included the Stonemasters – including Mike Graham, Ron Kauk, John Long, Richard Harrison, Tobin Sorenson, and Lynn Hill –teenage climbers from Southern California who were transforming American climbing.

“We smoked lots of bad weed,” recalls Bachar’s frequent partner, John Long, “and ran through the desert at night to develop our space perception, did all kinds of jackass stuff.”

In 1975, Long introduced 18-year-old Bachar to free soloing and they followed up with circuits of unroped climbing that linked together thousands of feet of rock. On a Half Dome Day, where they climbed 20 pitches solo Long, in his classic story “The Only Blasphemy,” recalled “scores of milling climbers” watching them, and Bachar’s “sly candid snicker” as he looked down off the top of a 5.11 solo, Long was about to do. The next day, Bachar did an El Capitan day with 30 pitches, but without Long.

It would be an incredible summer in Yosemite. With Stonemasters Tobin Sorenson, Ron Kauk, Kevin Worrall, Mike Graham, and Valley regular Jim Bridwell, he made the first free ascent of Free Blast 5.11b, the first half of the Salathé Wall. He joined Kauk and Long ton the first free ascent of the East Face of Washington Column, which they renamed Astroman. It was the first Yosemite big wall from the aid era to go completely free and Bachar unlocked the crux on the third pitch.

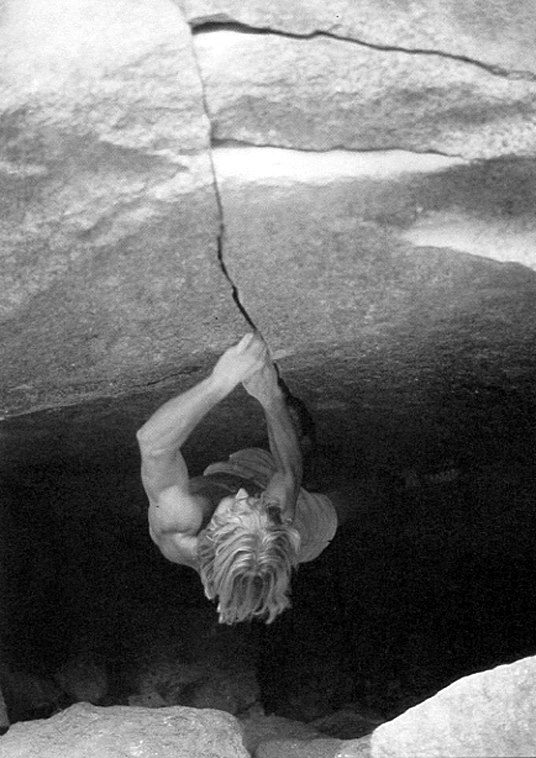

Of Bachar’s numerous short routes that season, the FIRST FREE ASCENT of Hotline with Kauk was perhaps the most important, as it became the first recognized 5.12 in Yosemite. He also took his soloing to a new level. Most of the Joshua Tree solos were short enough to be done in a few minutes. A ground fall from the first half of many Josha Tree routes might conceivably be survived. Bachar’s solo of the 400-foot long New Dimensions, 5.11a proved that he was willing to go unroped on a very hard climb where a mistake would cost him his life. “The mainstream [climbing] magazines just thought it was great,” said Bachar in a later interview with Michael Reardon, “but all the other climbers just hated me…take the rope off and that’s free climbing.”

Bachar might have been overstating the negative reaction to his solos, but in any case, he occasionally stoked his reputation for competitiveness and arrogance with gestures like posting a notice on the Camp 4 noticeboard, offering 10,000$ to anyone who would follow him on the rock for a day. No one took him up on the offer. Valley stalwarts like Royal Robbins, who had survived his own competitive era in climbing were amused and pleased to see the traditions of Yosemite carried forward.

In 1976, he attended UCLA and had superb marks, but decided that his heart was in climbing. His father, a logical thinker dedicated to the notion that total immersion and commitment rendered the best results, would have preferred that his son dedicate himself to academia, but accepted his choice.

Now Bachar parked his Volkswagen van there for most of the winter and in Yosemite in the summer. He dedicated himself to training and pushing the limits of climbing. Bachar had an even harder plan than college. He studied training, kinesiology and diet with an academic intensity and adapted it for climbing training. He improvised devices like the Bachar Ladder, and installed them at his campsite in Yosemite. He discovered Bruce Lee’s posthumous book, The Tao of Jeet Kune Do, with its exhortations to “be like water” and utilize “an economy of motions.” Bachar was also impressed by the films, in which Lee’s movement and physique were on dramatic display.

He was the first person Stonemaster Lynn Hill knew who climbed full time. “We were the only people he hung out with,” wrote Hill, “and we joined him every weekend or holiday that was possible.”

He ran and was rarely was seen in anything but running shorts and shoes. Foreign climbers like French star Patrick Edlinger covertly watched him training, and emulated his regimens.

In 1978, Bachar added two of the hardest climbs in Joshua Tree with Leave It To Beaver 5.11d, and the finger crack of Equinox 5.12d, using a top rope. He would return to make the first lead of Leave it to Beaver, the next year. It was a tactic he would later use for the first ascent of Baby Apes, 5.12b. In Yosemite, he made the second ascent of Kauk’s boulder problem, Midnight Lightning, which became a rite of passage for Valley climbers. Although he had concentrated on shorter routes, he also set a speed record of 15 hours for the Nose, with Mike Lechlinski.

Despite suffering a serious ground fall on a 1979 solo attempt on Clever Lever, 5.12a, in Colorado, that seasons he made his most audacious solo yet. Nabisco Wall in Yosemite was still a testpiece for the best climbers and comprised Waverley Wafer, 5.10c, Butterballs, a 5.11c finger crack, and Butterfingers a 5.11a thin crack. The hardest pitch, Butterballs, was continuous, hard to reverse and there was no chance of surviving a ground fall. In 1980, Bachar followed it up with a free-solo of the even longer Moratorium, a 500 foot long corner with smooth, insecure cruxes. He struggled at the crux, two thirds of the way up the route, and even wanted to downclimb from the crux but was so insecure in the flaring corner that he had to continue to the top. In his words, he was “completely hollowed out, I just got away with some bullshit.” After Moratorium he took a more conservative approach to free soloing. Control was the essence of his approach and philosophy, and when it was not possible, he knew to back off.

Although he had guided one seasons for Michael Covington’s Fantasy Ridge company in Colrado, Bachar had never made money just for climbing until the early 1980s, when he appeared with Bridwell on a 7-Up commercial, “That’s incredible,” where he soloed Leave it to Beaver 5.11d and More Monkey Than Funky, 5.11b, in Joshua Tree. He also competed in “Survival of the Fittest” on NBC “Sports World”, where he and fellow Stonemaster sparred with padded sticks on a narrow bridge over a river. Bachar won. Pop culture recognition was a step towards national consciousness that America was home to some of the best climbers in the world.

Bachar used the money from his TV appearances to hang out in Joshua Tree and Yosemite, play the saxophone and continue to push the limits on rock.

In 1981, he was invited to a climbing meet in Frankenjura, Germany, where he made several first scents, including Chasin the Trane 5.12d, a reference to his saxophone hero, John Coltrane – Bachar referring to Coltrane; and Metamorphose 8+ or 5.12a/b.

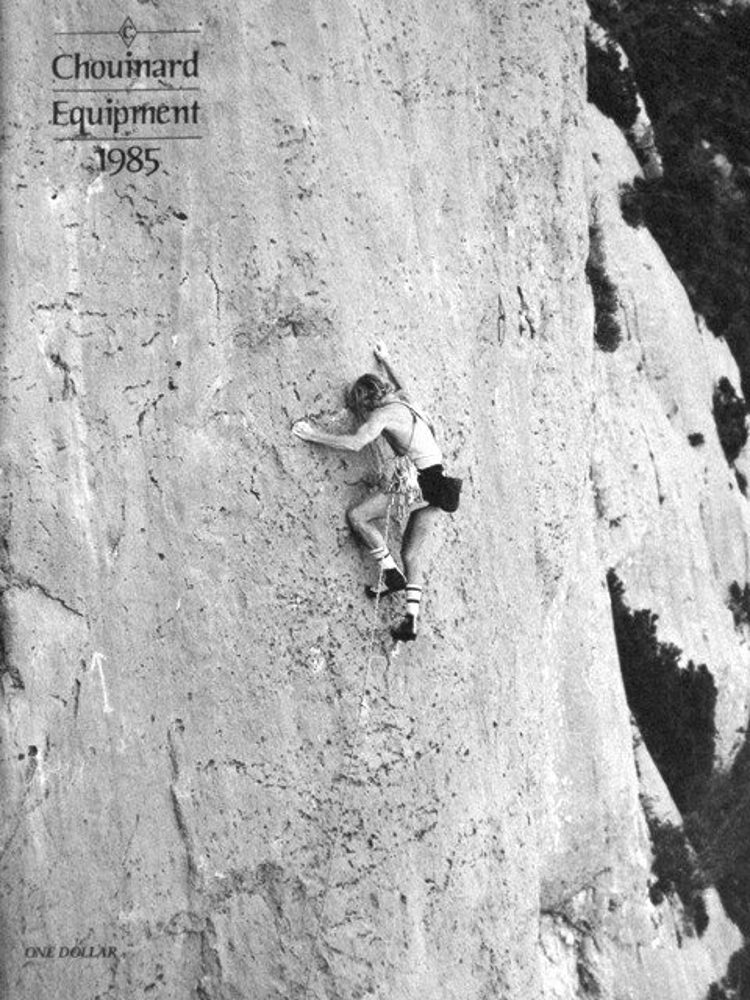

In 1981, Bachar, with Dave Yerian, completed what he and many others considered his masterpiece. The Bachar-Yerian, a 400-foot 5.11c up a vertical to slightly overhanging streak on Tuolumne Meadows’s Medlicott Dome was put up on lead, onsight, with the climbers hanging from hooks on flakes to place the sparse bolts. The second pitch, at 5.11, had only three bolts in 120 feet.

The route became a testament to Bachar and the Stonemasters, who had learned boldness and athletic movement as facets of a single sport. The few parties who repeated it noted its beauty, difficulty, and significance. Alan Nelson, who repeated the Bachar-Yerian in 1984, wrote, “The path of the master waits patiently, the way of the future transposed into the present. Its brilliance may be appreciated by many from below, but that’s just a pale reflection of the experience of following the path. The hazards are many, but when one reaches the end, one has transcended the mundane to become a master of one’s destiny.”

The rapid growth of climbing and the introduction of sport climbing ethics, with top-down cleaning and bolting annoyed Bachar. His comment that “there are more weenies out there than ever,” was understandable from his Olympian perspective, and his often stated disdain for sport climbing gave him a reputation for a thorny attitude. He was involved in an incident where a punch was thrown in the Camp 4 parking lot after a climb on Cottage Dome in Tuolumne was rappel-bolted and bolt hangers were flattened on Arch Rock. Mostly, however, Bachar answered the rise of sport climbing with a series of very hard routes in Joshua Tree and Yosemite, including leads of Moonbeam Crack 5.12d, Acid Crack 5.12d and a solo of Father Figure 5.13a, all in Joshua Tree

In 1986, he teamed up with Canadian soloist Peter Croft, who had taken free-soloing to even longer hard routes than Bachar with his first free ascent of the Rostrum 5.11, for one of the biggest enchainments ever. The pair flew up The Nose of El Capitan and the Northwest Face of Half Dome in 20 hours and 19 minutes. Croft was impressed by his companion’s strength and poise. When a six foot-high flake Croft had climbed started to fall of the wall, Bachar simply pushed it back in place with a casualness Croft associated with superheroes.

Through the 1990s, Bachar continued to climb hard, but mostly out of the public eye. In 1996, his son, Tyrus was born. In the 2000s, he started a climbing shoe business and survived a serious car accident in 2006, where his business partner, Steve Karafa was killed. Bachar died from a fall while free-soloing at Dike Wall near Mammoth Lakes, California, in 2009, depriving climbing of one of its most exacting masters and philosophers. His routes and feats live on as adventurous examples of the finest that American rock climbing culture can provide.