George Whitmore: Pioneer Rock Climber Who Made the First Ascent of The Nose, Dies at 89

On Jan. 1, Whitmore, born in 1931, passed in a California hospice facility due to complications from Covid-19

Photo by: Fresno Bee/Yosemite Climbing Association archives

Photo by: Fresno Bee/Yosemite Climbing Association archives

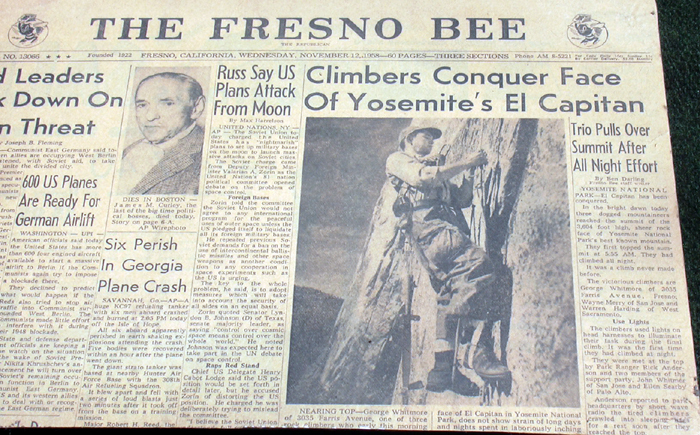

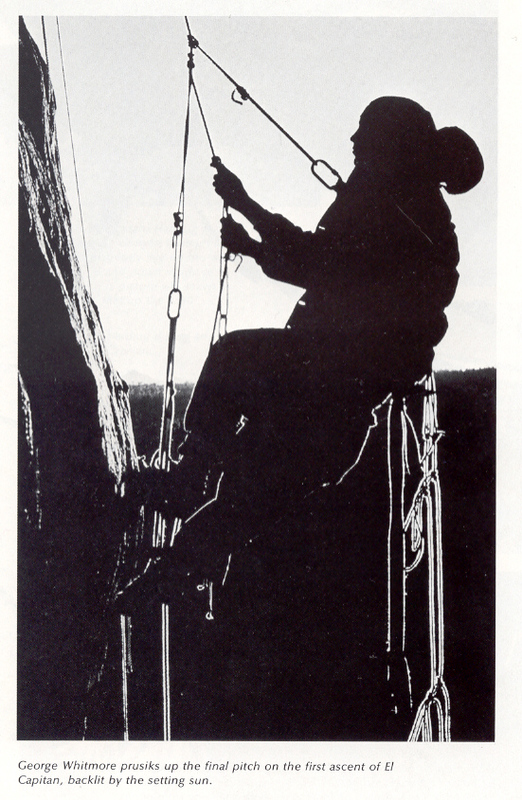

Climbers Conquer Face of Yosemite’s El Capitan: Trio pulls over summit after all-night effort,” read a Fresno Bee headline in 1958. A large photo of then 27-year-old George Whitmore showed him high on the wall dressed in military fatigues, a baseball cap, and a long-sleeve shirt. Smiling, he focused on adjusting his prusiks while ascending a fixed Gold Line.

From Fresno California, Whitmore began climbing in 1953 while a pharmacy student at UC San Francisco. By chance, he shared a house with climbers who turned him onto the sport. He partnered with them and also took trips to the Pinnacles National Park with the Sierra Club. After UCSF, Whitmore joined the Air Force and went on active duty. When he returned, he learned that Half Dome had been climbed and that Warren Harding had begun work on The Nose on El Cap in a climb that had stretched out for more than a year.

Warren Harding, Wayne Merry and George Whitmore made the first ascent of The Nose, requiring 45 days of fixing pitches over 3,000 feet. The team spent 12 days on the final push which they completed on November 12, 1958, at 6 a.m.

“There was this great uncertainty, is it possible, nobody knew,” Whitmore told filmmaker Eric Paul Zamora while recounting the historic climb. During their ascent, the team’s fixed hemp ropes hung in place through winter storms and spring runoff, and rats ate their sleeping bags stashed on ledges.

As word of their climb grew, people craning their necks in El Cap meadow caused traffic jams. In turn, the Park Service pressured the team to either finish or retreat.

Whitmore joined Harding on The Nose midway through after two others stepped off the team. By now, ropes snaked their way 1,000 feet up the wall. Whitmore was tasked with helping the team make it to Dolt Tower, which required overcoming the Stoveleg Cracks, named after the pitons forged from stove legs found at a dump. In addition to managing the ropes and chaos associated with big wall climbing, Whitmore hauled heavy loads up the wall day after day.

“I was involved in developing and making some of the gear that was key to getting to the top of Dolt Tower on Thanksgiving weekend of 1957,” he told Carmen George at the Fresno Bee. “I’ve gone down in the books as having been the Sherpa who hauled loads while the heroes did the climbing, but actually I was on the climbing rope part of the time pushing the high point, and in fact, I would have been up there pushing the high point more except Wayne (Merry) couldn’t handle the hauling.”

“Whitmore made a variety of large pitons out of aluminum to reduce weight. He made these pitons to fit the wider cracks found on The Nose,” Ken Yager, founder of the Yosemite Climbing Association, says.

“George didn’t talk a lot, but I always liked him,” Rich Calderwood says, who was on The Nose first ascent team before retreating from Camp 5. “In fact, he was always a quiet guy, even on the climb, as I recall.”

The Nose climb was also successful because Whitmore brought bolts up the wall that Harding needed to drill the final bolt ladder to the top of the summit overhangs. It was an epic all-night struggle. The team fought against gravity and exposure as Harding climbed with the mantra, “until we finish it, or it finishes us.” The route culminated with Harding’s 14-hour lead as he pounded in the final bolt as the sun rose over the Sierra. The trio was joined on the summit by two friends who served them champagne in glasses.

Harding died in February 2002 and Wayne Merry in December 2019.

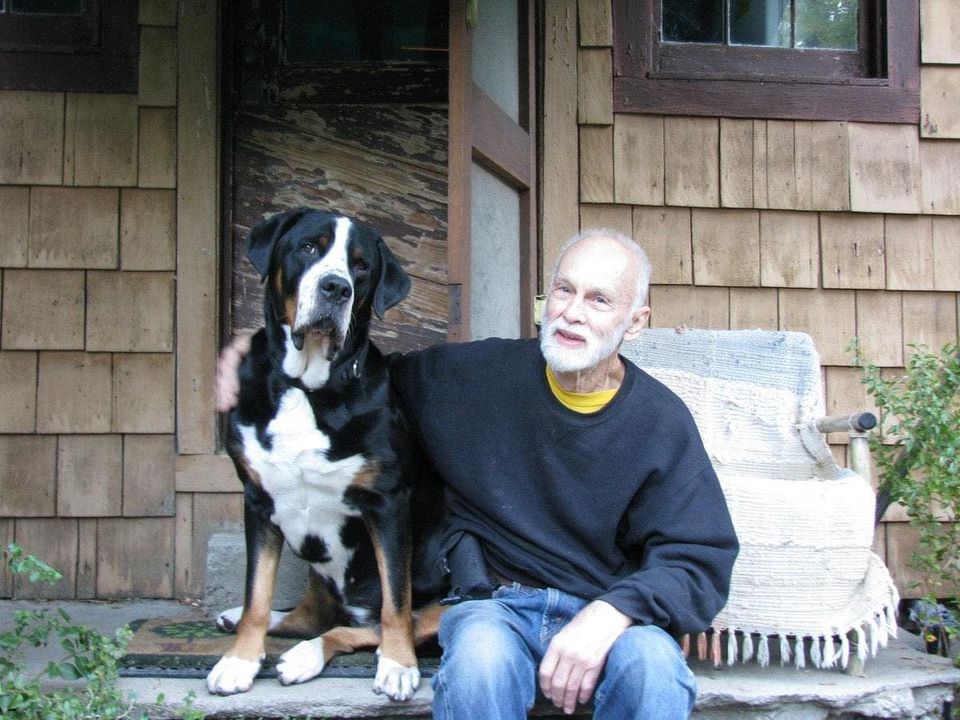

Whitmore worked as a pharmacist and continued to climb through his 89 years, including, in his mid-70s, making an ascent of Cathedral Peak in Tuolumne Meadows. He was an activist and lobbied for the California Wilderness Act of 1984 — which protected the Ansel Adams Wilderness, the Dinkey Lakes Wilderness and Monarch Wilderness, and sections of the John Muir. His hard work culminated in the creation of both the Mineral King Wilderness and the Kaiser.

His wife Nancy survives him.

Yosemite Local Holly Webb Remembers Her Friend

“George was such a multifaceted, amazing person,” Yosemite climber and resident Holly Webb told me today through tears. In his final years Whitmore visited her and her husband, enjoying hikes with them and their dogs. “I can’t believe he’s not going to reach his 90th birthday. He’s always been the youngest old person I’ve ever known.”

Before he contacted Covid-19, Webb described Whitmore as active and healthy. “He was energetic and spry, almost like an elf,” Webb says. “He loved to hike, and work, and he loved people — it’s a real tragedy.” After being admitted to the hospital where he recovered, his health depleted quickly after being discharged. Though Covid free at the time of his death at Sierra Vista Healthcare in Fresno, his body failed due to complications from the virus.

Though Whitmore’s wife Nancy was with him when he died, non-family was only allowed visits through the glass. On New Year’s Day, Webb and her husband Jeff, and their dog came to the hospice to see their friend one last time.

“It was sunny outside,” she says of the final moments. “I put my hand on the window to look in, and he looked very weakened. I told George how much I loved him and missed him and how bad I felt that I hadn’t seen him this year because of Covid. I told him I would see him again soon. He couldn’t speak clearly, but I could tell he said thank you.

“We lifted our dog up so he could see him through the glass, and he called her a good dog. He told me he wanted to go home. George wanted to die doing something, being active in the world.”

Though Whitmore wanted to die being active in the world, the gift he and his team brought through the first ascent of The Nose guaranteed that his effort would allow others to share in what was so important to him for generations to come.