50 Years of Climbing on the Squamish Sheriff’s Badge

And the unrepeated Daily Universe that climbs through the big roof

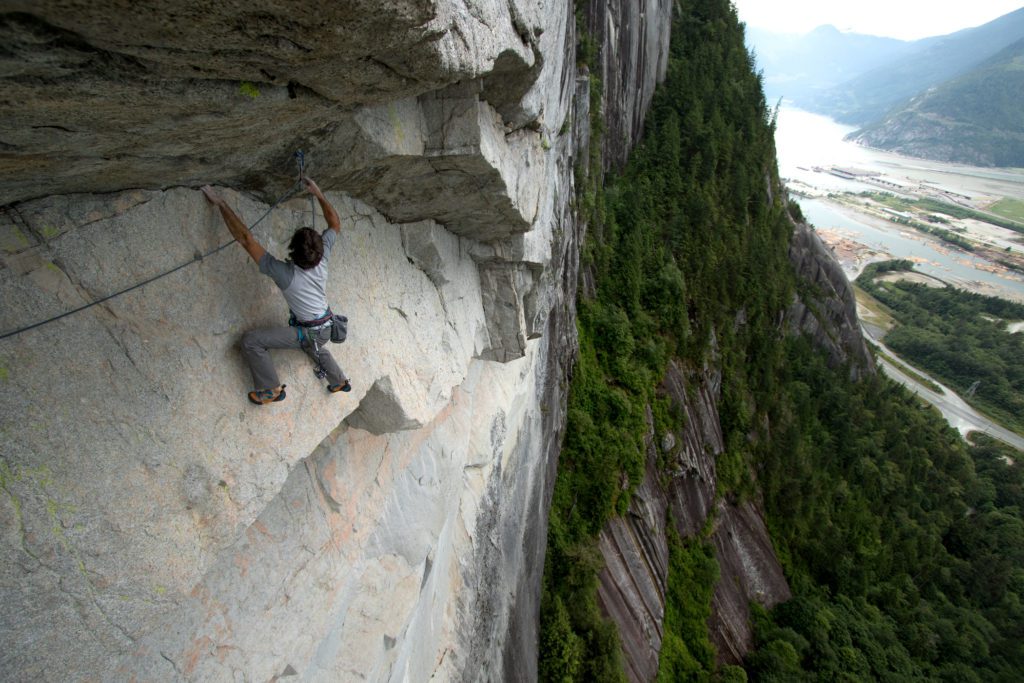

The following was written by Squamish-based photographer and climbers Kieran Brownie, who’s image of Brette Harrington on the Chinese Puzzle Wall is the cover of this year’s Canadian Alpine Journal.

It was July 2016 and my feet were numb; the harness I had been sitting in for the last 4 hours had cut through the fat of my thighs and was restricting blood flow. I cursed myself for not bringing a belay seat as I awkwardly leaned away from the wall to get a glimpse of Will Stanhope, just below me, but 30 feet away as he entered the Escher-esque horizontal monstrosity that protrudes dramatically half-way up the Sheriff’s Badge.

In 1962, 25 years before Stanhope was born; Fred Beckey, Les Macdonald and Hank Mather had skirted the upper ridge of this wall, the Angel’s Crest -noted by Beckey as one of the top 50 North American classics- has seen thousands of ascents since it was first climbed due to the unrivalled position atop the Badge –it provides many climbers with their first taste of an alpine adventure. Although Beckey scooped the ultra-classic ridge line, local climbers were still eying the outrageous gold pentangle rock-scar below; one could estimate it being 500 metres tall, 2/3rds of which are overhung, and then there was the Big Roof, would it even go? What would happen if it did? In 1976 Paul Prio and Greg Shannan couldn’t resist their curiosity any longer; The Sheriff’s Badge A4 was cutting edge in commitment for the area, Prio and Shannan established a new standard for the locals to test themselves against. Steve Sutten aid-soloed it shortly after, one of the first major solo walls in Squamish.

As was the status quo at the time, all ascents were ground-up and thus a by-any-means methodology was necessary, but once word was out that a route was possible it was just a matter of time until someone came along to realize the climbs potential. For instance, Angels Crest was climbed in two parts, at first Beckey et al approached via the North Gully, accessing the ridge just below the Acrophobes, Beckey would return later with Eric Bjornstad to climb the lower pitches. At the time, climbers couldn’t be bothered to consider such matters as free climbing, first-ascents were to be had. In 1975, 15 years after the first ascent, Dave Loecks, P. Charak and L. DuBois would climb Angels Crest from the ground, without aid.

The underlying competitive nature within the climbing community has always been to improve upon the style of previous ascents. If it can be climbed in five days, can it go in one? If it can be aided, can it go free? If it can be red-pointed, can it be on-sighted? If it can be on-sighted, can it be free-soloed? It is a form of distillation, the process of many generations slowly boiling down a discipline to its essence. The cathartic pursuit – though purifying – is born from certain energies that can also cause great harm. As in the incidental (and unintentional) first prospective “in a day” ascent of the Sheriff’s Badge in 2000; when the leader, Chris Geisler, took an unexpected fall in mundane terrain and broke his leg, forcing a reluctant retreat. Geisler is no stranger to this wall though, and no slouch – his new-age A5 route The Temptation of St. Anthony stood as the least likely route to be repeated (ever). That was until in 2011 when 23-year-old Marc-Andre Leclerc began exploring the seven-pitch route as a free climb. Apart from adding a variant to the second pitch (which he aided, placing protection bolts on lead) Leclerc did not alter the route, even when faced with pitch-four where a thin white dyke splits a black wall. Three bolts protect the first 30 metres of serious climbing up to 5.12+ and the difficulty relents for the final 20 metres. This pitch, which Marc-Andre named Cerebral Fornication; went free at 5.12d r/x in 2013, closing a two-year project that had required hundreds of hours of effort from Leclerc and friends.

This is the new standard, these new-wave ascents often require odious amounts of work to prepare. Cracks choked with dirt and rainforest must be excavated, loose blocks trundled, and for the harder pitches the holds need to be cleaned. In modern day Squamish, so much of the bedrock has been exposed that it almost seems as if it was always this way, but without heavy cleaning practices most of the granite would still be buried under a foot of dirt and moss, except for the steepest walls. Hundreds of thousands of hours of hard labour have gone into preparing the experience for us. It is a massive impact, one that started small in the mid 1970s as a new generation of climbers became interested in pushing the athletic standards on the smaller rocks, crags which the hardcore had considered piddly, mere stepping stones on the path to the alpine -why bother wasting time on “practice rocks” they would say. But it is in this era, sometimes referred to as “the golden age,” when Squamish climbing as we see it today began to take shape. A dedicated group were beginning to feel their way up the granite, squandering the unquenchable energy of their youth on pursuits considered meaningless among the mainstream culture.

Their names are linked to routes that are sought after by thousands of climbers each year: Perry Beckham, Scott Cosgrove, Peter Croft, Tami Knight, Hamish Fraser and Eric Weinstein (among many others) are linked to a period of Squamish climbing that paralleled the Stone Masters in Yosemite. It was an era of freedom and of exploring the unknown for those with the privilege to do so. The local free-climbing standards rose rapidly; 5.12 became the new norm beginning with Eric Weinsteins 5.12a Sentry Box at Murrin Park in ’75, followed by a host of hard climbs around Squamish, most of which still stand as test-pieces for the modern trad-smith. As they worked their way through the plums, a few of the tribe began to take these new abilities to the big-stone. In 1981, Perry Beckham and Blake Robinson explored a strikingly clean dihedral on the bottom left edge of the Sheriff’s Badge and a year later, Beckham freed the route at 5.12a with Mike Beaubien and John Simpson. Simpson returned that year and soloed a second pitch, prepping it for Beckham and Beaubien who unlocked it before continuing up to complete a third pitch, which Croft freed after on-sighting the first two pitches with Hamish Fraser. By the end of 1982, The Daily Planet was three pitches long, still shy of the great roof, and the way forward was unclear and considered damn near impossible.

Before 1982 was over, Beckham, Beaubien and Simpson established another route in the area called Blazing Saddles. It’s a classic 5.10 crack on the left edge of the Terrace (the ramp that accesses The Daily Planet). Croft would return to the Terrace in ’84 to free Astronomy (originally Mad Englishman and Poodle A1) at 5.12b, slightly upping the ante. McLane and Beckham joined forces in 1985, adding a three-pitch 5.11+ called Hot Rod, also off the Terrace. One year later, Beckham was back, adding a fourth pitch at 5.12b to The Daily Planet with Brooke Sandahl. They came within arms-reach of the massive roof before calling it off. Beckham would return in ’89, alone, with his focus on the centre of the wall and the possibility of a new aid-route. He retreated after three pitches, but his infatuation with the wall would reach beyond the golden age.

In 1999, when Matt Maddaloni and Damien Kelly (the up-and-coming young guns) were repeating the namesake Sheriff’s Badge route, they spotted bolts in the middle of nowhere which on their return they questioned Beckham about. Beckham, seemingly caught up in the flow of life, started as if he had forgotten to turn the oven off and a few days later, and 10 years after it began, he topped-out Cowboys and Indians A3, solo. It is one of the most outstanding moderate aid-lines on The Chief in terms of position and quality of rock. During Beckham’s decade-long hiatus during the 90’s, the Badge had seen more contributions. In ’97 Susan Bolton, David Harris and Eric Hirst linked discontinuous crack systems above the Terrace towards the lower pitches of Angels Crest and called it Borderline 5.10d. It’s another “classic” by todays standards and is a variation to Beckey’s Angels Crest. It addsa few bonus pitches of delightful 5.10 climbing to an already stellar outing.

Maddaloni and Kelly were among a new generation of climbers that had arrived. In 1996, Skull Fuck, a techno-aid A5 nightmare through the entirety of the white wall was authored by the increasingly agro duo of Sean Isaac and S. Easton (their Canadian Alpine Journal entry is both hilarious and horrifying). The second ascent was quickly claimed by Chris Geisler, solo, to which he described as no-big-deal despite commuting from his tent to his high-point every day, while simultaneously organizing an insurance claim. In 1999, the notorious Andrew Boyd would make his contribution with Derrick Horne and Mike Mott. I Shot the Sheriff A4 is a committing line on the less explored right side of the Badge, the wall is steep and scale is easy to lose as the imposing roof crowds your peripheries. As the millennium loomed, the Badge was beginning to fill in with the imaginative visions of four generations of Squamish climber and as a result, the question was no longer would it go free, but when.

In 2001, Croft returned from his adopted home range of the Californian Sierras to catch up with friends in his old stomping ground. Plans were made to revisit The Daily Planet. Hamish Fraser, who Croft has described as the best climber you’ve never heard of, along with Greg Foweraker had been eyeing the possibility of freeing the Big Roof and continuing to the top of the badge. The three climbers spent several days poking at the problem, exploring every direction until they finally discovered a way through the Roof in the dark rock off to the left. Croft aided the last two pitches with Dave Humphreys to reach the walls logical finish, Sasquatch Ledge, where they fixed ropes for easy access.

Croft and Foweraker spent a day scrubbing in the rain to prepare these pitches and on the last day of the trip, Croft and Fraser freed the five-pitch addition despite the lingering wetness. They named it The Fortress (of Solitude) to honour the seemingly impenetrable Big Roof. A wonderful example of Crofts resolve is printed in the 2001 Canadian Alpine Journal entry, “On the down-side there was no shining summit, I had to yo-yo the wet 5.12 pitch and worst of all, Greg (Foweraker) wasn’t there. On the up side, we got buttered in mud and after finishing our climb after sunset, had to feel our way down in pitch dark, on all fours, like bugs. Perfect.”

In 2015, 40 years after the first ascent of the Sheriff’s Badge, Tony McLane and Jorge Aakermaan set off from the top of The Daily Planet, forging into terrain deemed unclimbable by their heroes. The vision was a new free variation to the top of the wall that would solve the problem of the Big Roof, once and for all. Where Croft and Fraser had gone left, The Daily Universe traversed right, joining the original Sheriff’s Badge aid route through the Big Roof via a series of difficult boulder problems. In the end, they sent a new 17-pitch 5.12c free-route.

This is where we started the story, with Will Stanhope considering his next move. He gave the sequence a final thought before committing, with his feet were tucked into his chest, his hands almost at the same level and below him a thousand feet of air.

He generated force through some ineffable means and hoisted himself upwards, stabbing a long arm at a shallow pocket under the main roof, he missed. The air rushed up to greet him as he plummeted. He stared up at the spot he just came from, a slow “FuUUuck” escaped his lips as he slowly rotated at the end of the rope, now level with Tony McLane at the belay. The climbing is physical and unforgiving, no place for subtleties or second chances. Stanhope swang back to the belay and untied, pulling the rope to give the pitch another go, only to come flying off a second time.

A few weeks later, I found myself at the lip of the Big Roof again, Stanhope had sent the boulder problem and was battling to turn the lip, but just as he seemed to solve the sequence, he was pumped off the rock on the final moves. After resting for a minute, the climbing appeared mundane, so close. About 50 metres of dynamic moves between slopers weave between patches of friable rock with a mixture of bolts and cracks. By the time they finished climbing it was dark and their long descent was illuminated by cell-phone. Stanhope’s ground-up efforts were impressive but, as of yet, the route has not seen a second free ascent.

Over the course of almost 60 years, the white stone of the Sheriff’s Badge has reflected the values and desires of a tenacious group of individuals known as Squamish climbers. Their clothes have changed, the equipment is now refined and the style has progressed, but the same question that has burned brightly in the imaginations of each generation will be asked by this one; what’s next?