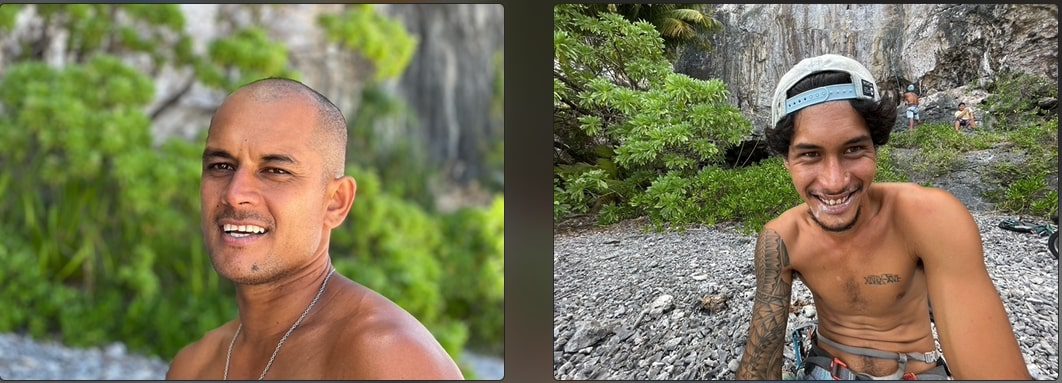

Heitapu “Tapu” Mai: The Architect of Makatea’s Climbing Renaissance

Mai shares his goals of transforming Makatea into a global climbing destination while nurturing the island’s natural and cultural heritage

Photo by: Chris Van Leuven

Photo by: Chris Van Leuven

It’s a chilly January day in the Sierra foothills outside Yosemite when I ring up my friend Heitapu “Tapu” Mai in French Polynesia to get the latest update on his efforts to make the island of Makatea a worldwide tourist destination.

Tapu, 39, shirtless due to the heat, picks up the video call at his home in Tahiti, where he’s between meetings with the French Polynesia tourism board with a friendly “Hey broo” and releases his wide grin and toothy smile. It’s a grin I’ve seen dozens of times since meeting him two years ago during my first visit to the islands of Tahiti. When I landed there by speedboat in 2021, looked up at the gorgeous walls shooting out of the Pacific Ocean, and connected with Tapu, I knew I was in the right place, somewhere I could see my future. Sometimes, you just know when you’re in the right place – like how I felt when coming to Yosemite for the first time to climb in the ‘90s.

Makatea is that good — world-class — but it’s barely developed.

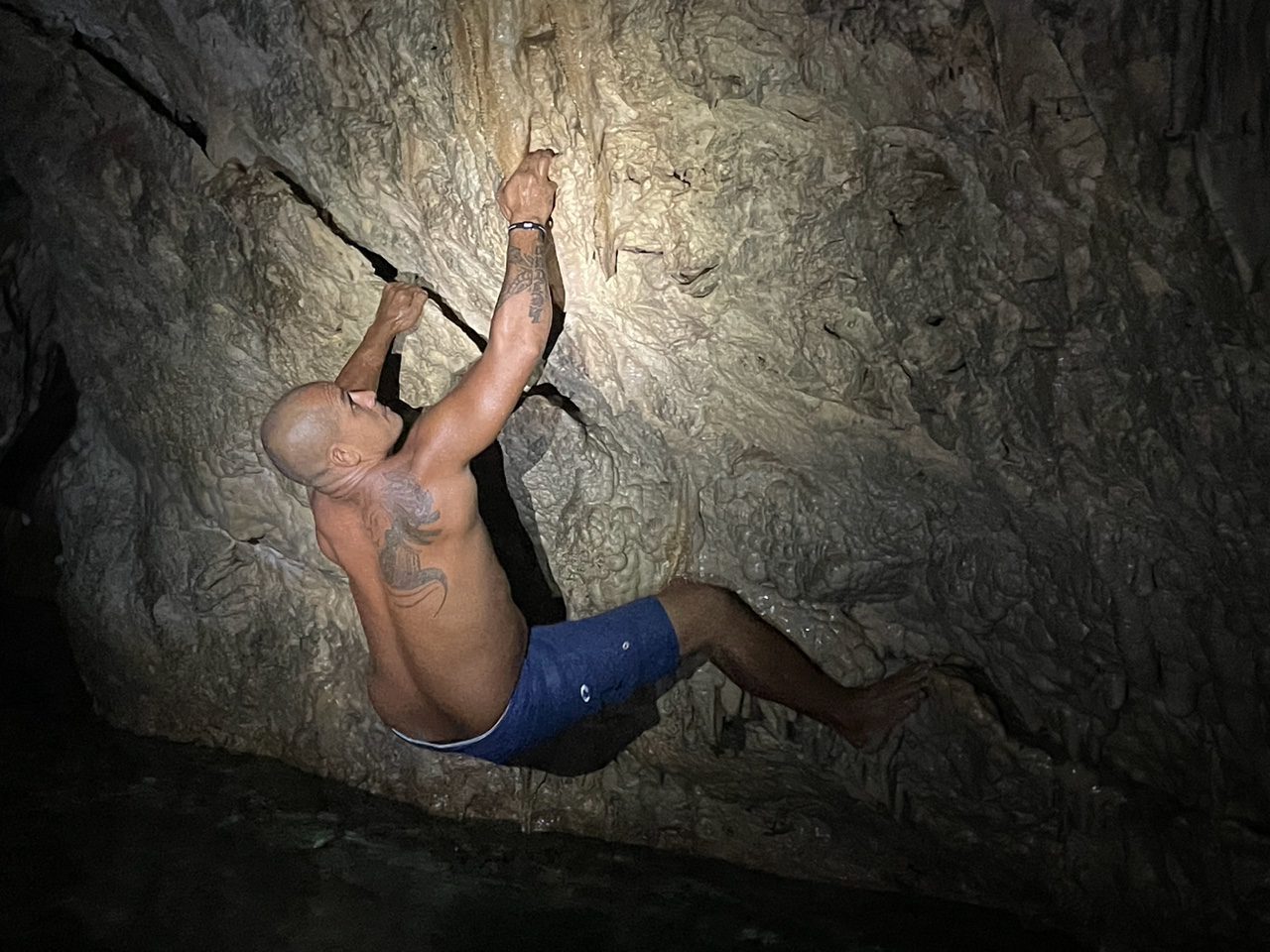

Unlike Yosemite’s granite walls, which are peppered with thousands of routes that zig-zag up the gigantic faces, Makatea’s limestone walls are sheer white, gray, and black, with single to three pitch lines stretching from the beach to the jungle at the top of the wall. It contains five sectors offering some 100 routes, with potential for hundreds more.

The difficulty is that Makatea is 4,000 miles from me here in California, which requires an eight-hour flight from Los Angeles to Tahiti, an additional quick flight to Rangiroa, and a multi-hour speedboat ride that rips through the open ocean. Traveling to Makatea may be expensive and lengthy, but the lodging, activities, and food are comparably affordable once you’re there.

I wrote in my journal during the first visit:

The boat ride to Makatea was bumpy and long. At one point, I had the captain stop so I could put on more sun protection and my foldable sun hat, as I didn’t want to burn my skin further.

When we landed, we pulled into an aging phosphate loading port. A giant sign guarded the entrance, looking like something out of a zombie apocalypse. Covid 19 was written in big white letters, giving dates of the outbreak and containment. Concrete piers and broken and rusting steel surrounded our small motorboat. Julian, my host and Tapu’s dad, picked me up. We followed a coral road laid over train tracks to his place. Rusting train cars overgrown with jungle covered the hillsides of the world’s highest atoll. Makatea, one of the raised coral islands in the Tuamotu Archipelago, has a geological history that involves uplifting coral reefs and exposing rich phosphate deposits. These phosphate deposits, created over centuries, made the island a significant site for phosphate mining. Millions of tons of the white, gray, and tan powder were extracted from 1906 to 1966, with boats from Japan and surrounding countries making frequent trips to collect it. In ‘66, operations closed overnight, and 3,000 workers were suddenly out. Everyone but a few dozen left, and the island was mostly forgotten. Today, old power lines, decrepit factories, and aging train tracks parallel a modern cell phone tower, oil drums, and four-door trucks. Giant white limestone walls surround the island. The ground crunches underfoot, where white coral is the foundation for everything.

This is where Tapu grew up among some 60 neighbors who live on the island. His dad, a former professional dancer, raised Tapu and his brother Tarariki on the island. They attended small schools set within thin platform walls. The boys, now grown and with their own families, spent their childhood fishing, hiking, hunting coconut crabs, and caving. At 18, Tapu moved to Tahiti for work, and today, he shares his time between his homes on the two islands 100 miles apart. Here, he and his wife Minarii raise his 13-year-old daughter, while Tapu guides outings in Makatea with rope access work and rescue training in Tahiti.

He tells me his daughter, Hanatea, has climbed a few times and that his wife doesn’t, but “she helps me a lot with bolting, organizing the climbing trips, and gives me ideas to make good routes.” His main climbing partner is his brother, who lives with his family down the street in Makatea.

I asked him how sport climbing came to be on Makatea.

He says he was sick of hearing about mining on the island. “While I was growing up, all the people, when they talk about Makatea, they talk about it for phosphate extraction,” he says.

Phosphate mining isn’t the only reason Makatea was occupied. Polynesian settlers arrived there around 800 AD where they used Makatea’s fertile soil to grow crops such as taro, coconut, and breadfruit. They also fished in the surrounding waters.

Fast forward to 2018. Over a beer in Makatea with his friends from a society of professional rope access, canyoneering, and climbing in French Polynesia called Acropol, Tapu started spitballing ideas.

“We decided to do other things for the island, and we chose the vertical activities,” he says. They chose rock climbing for the initial stage, then added via Ferrata. But first, they had to come up with money to bolt the cliffs. Tapu applied for a grant from the Ministry of Tourism and Sports in French Polynesia, which supported his project and funded the hardware for some 40 routes.

Next, Tapu reached out to Maewan, an organization that operates as an adventure base for exploration and environmental projects. Maewan helped Tapu spread the word and contact Petzl, Arc’teryx, and others. This led to Jonathan Siegrist, Nina Caprez, and crew coming in 2019 for three weeks, where they bolted an additional 60 routes.

In 2021 and 2022, I made two trips, first to pen a story on a shark swimmer on the island of Tikehau and see Makatea, known as the “Forgotten Island.” Between incredible climbs on Makatea, I munched on different fruits, raw fish, coconut crab from the island, and food brought in on boats, including rice, chicken, and beef.

I was so impressed after my brief visit that upon returning to the States, I invited Sasha DiGiulian, who asked Brette Harrington, and a month later, I was back in Makatea. During this visit, Sasha filmed an episode of her show No Days Off, and Tapu and I began brainstorming about working together so I could continue to visit the island and help grow interest in the area.

I launched a website to help bring visitors to the island. Sasha’s video made it on the in-flight entertainment for Air Tahiti Nui. Due to Sasha and Brette’s social media influence, dozens of people contacted Tapu and me.

Another way Tapu spreads the word is through the annual Makatea Adventure Festival, where he hires a 200-passenger vessel from Tahiti overnight to shuttle visitors to the island. Now in its third year, the “festival includes all the activities you can do in Makatea: climbing, rappelling, via Ferrata, hiking, visiting the caves, snorkeling, and fishing,” he says. “You can spend your time hunting coconut crab or chilling in nature.”

The next Makatea Adventure Festival is coming up on from Sept. 16 to 20.

Beyond the climbing, the incredible views, and the warm locals, I ask him what really makes the island special.

He pauses. “Mana. The spirit of the island. I can feel it when I’m on the trails, the routes. When I close my eyes, close my mouth, and open my soul, of course you can feel it.”

To Tapu, it’s the combination of spirituality and the nature-based therapy of climbing the routes and exploring by foot on the island that makes it unique for him and the next generation.

He says his favorite route is the three-pitch Kaveu Night Fever, 5c (5.8), which he says can be accessed directly off the beach or from the top of the island and make three rappels down the route to begin. “I like it because it’s high, the view is beautiful, and it’s not too hard. You can see the big ocean, the reef, the sandy beach, and the coconut trees below. And if you are there in the morning, you can see the sunrise.”

“I hope the young people and the children, the next generation, try to get into these sports and activities and build their future on the island.” Instead of phosphate mining, which decimates the landscape, he says, “I think outdoor activities will be a big part of the island. For now, it’s me, my brother, and my friends. I want to see our children make the next step of the future.”