Defying Gravity: Justin Olsen’s Lens on Yosemite’s Sky Flyers

Olsen shares a six-year odyssey of capturing climbers, slackliners, and aerialists.

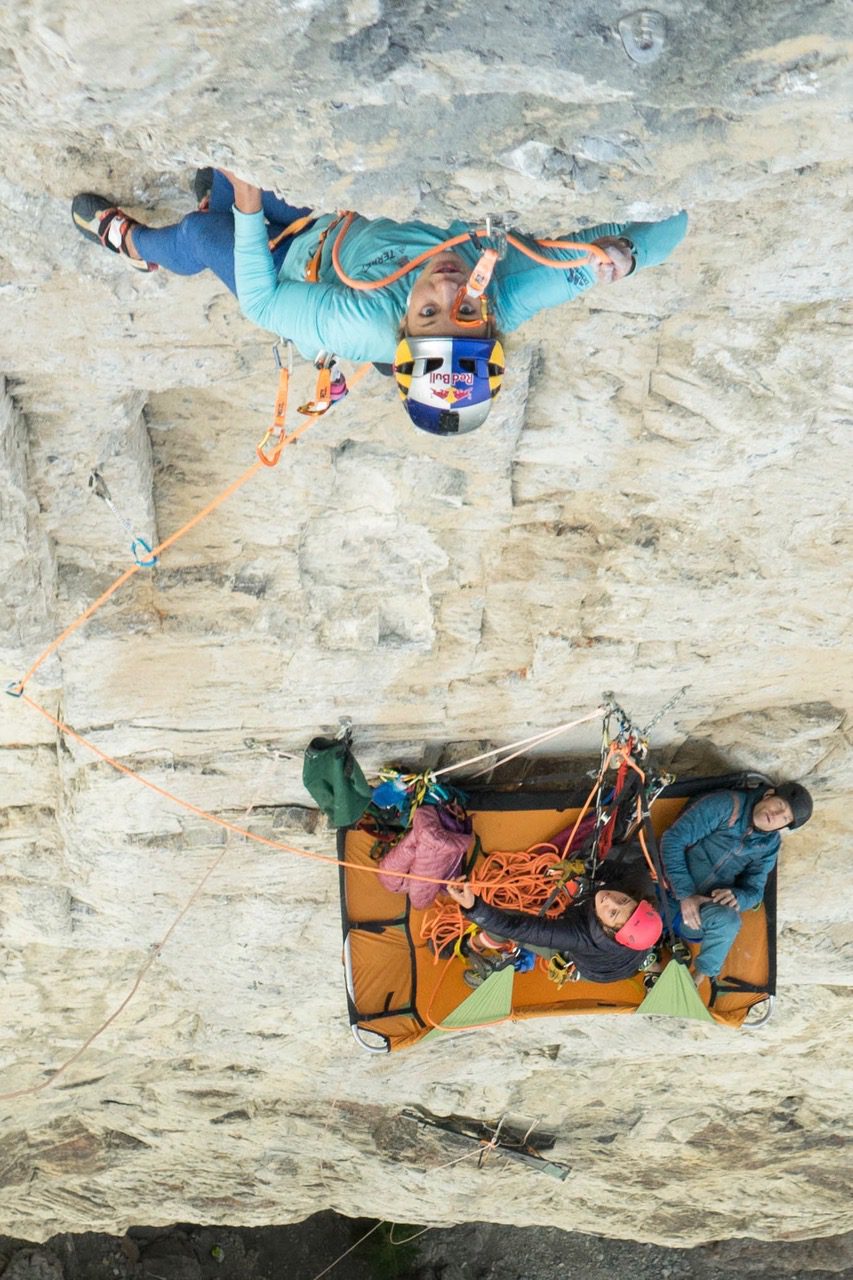

Photo by: Justin Olsen

Photo by: Justin Olsen

“Would you jump?” Photographer Justin Olsen asks his social media followers where he’s referring to his friend Daniel Bosch, who is flying like Superman — for his first rope jump — with two ropes tied to his harness helplessly dangling below and continuing out of the shot. Yosemite Falls thunders in the background as granite and blue sky surround the aerialist.

Olsen’s post continues: “A massive rope swing rigged off a highline in Yosemite [at Taft Point]. It’s a 60+ meter free fall until the rope catches, and then you swing.”

Though Olsen and I have crossed paths over the years — we’re both Valley denizens, with me now living nearby and him in the heart of the action—I wanted to know more about his work. Despite his imagery appearing in my stories in Men’s Journal, our paths crossed when our projects overlapped with pro climbers Kevin Jorgeson and Sasha DiGiulian, I didn’t know much about him. So, I rang him up this January at his tiny place tucked in the east end of the Valley floor.

Little Siberia

Curry Village is the coldest part of the Valley, a good ten to fifteen degrees chillier than anywhere nearby, so locals call it Little Siberia. Facing north and tucked under the giant wall of stone called Glacier Point Apron, the area receives a maximum of one hour of daylight during winter. It’s so cold there’s even an ice rink a stone’s throw from his place.

“Before I got into climbing, I really hated heights. I still do,” Justin Olsen (he prefers Olsen) tells me from his ten-by-twelve WOB cabin in the Curry Village employee housing area called Huff House (Housing Under Fire Fall).

A WOB (With Out Bath) is a hard-walled room without plumbing — standard housing for concession employees — with a heater, electricity, and space for one roommate. As I did in the ’90s, some locals coat the inside of their WOBs with tools for the area — portaledges, ropes, and cams. Olsen’s camera gear is scattered about in his Tetris furniture configuration, where his bed is over dressers, a mini fridge sits by the front door, and a chair is shoved up to a small desk under the bed. He likes living in a small place as it reminds him of family outings during his youth.

Early Years

“I was homeschooled, and my parents would take me on huge road trips, and we went camping all the time,” he says. “Being in tents is pretty normal for me.”

His childhood was spent in a mix of country and mountains in the small town of Cottonwood in Northern California along Interstate 5 near Redding. He picked up photography while attending a charter high school with more flexibility than traditional classrooms. He knew his science teacher, Jefferey Rich, spent his summers traveling the world and shooting assignments for National Geographic. He signed up when he found his teacher’s name attached to a photography elective.

“I don’t think I was very good at all, but I liked it,” Olsen says, adding that he didn’t pick up a camera again until moving to Yosemite.

From Cottonwood, he moved to Redding for community college before relocating to Chico because his brother attended University there. However, Olsen didn’t hit the books. Instead, he hung out with friends and passed the time without direction. One fateful day, while playing soccer with friends, Robert Zebley suggested he join him for work during the summer in Yosemite.

“It didn’t take too much convincing,” Olsen says of when he moved to the Valley in 2016. “I’ve always loved Yosemite. Gone camping there with my family, like, every year of my life.”

“I was just going to do three months here. That turned into four years.” After a short stint at Mammoth Mountaineering on the East Side of the Sierra, Olsen returned to the Park in 2023. He currently manages a bar (name omitted), where the evening work keeps his days free to spend with friends to photograph and film the best climbers, slackliners, and aerialists.

Capturing the Action

“I started climbing, hiking, and backpacking and wanted to capture the moments. So, I bought a camera and started capturing all the amazing people in this place. I’m not a highliner myself. I enjoy being there and watching these guys do their thing out there, and it’s fun for me to rappel in and capture them.”

Olsen’s first route was the two-pitch Jamcrack by Lower Yosemite Falls. The first pitch is slick as snot, and though it’s a “secure” hand crack rated merely 5.7, many suiters fail even to get off the ground. Pitch two, 5.9. pinches down to fingers toward the top. “It terrified me,” he says. But he stuck with it.

One day, Olsen was hanging out in the Community Center behind the Curry Ice Rink / rafting stand when he connected with local crusher Ryan Sheridan, who took him under his wing. Now torn down, the CC was a rotting trailer with a dark interior where employees would watch T.V., play ping pong, read, and party by night. He’d seen Ryan there many times, where he’d be hunched over a table and looking at hand-drawn climbing topos of big wall routes in the Park.

Like Olsen, Sheridan works for the concession. He rigs bolt-free highlines on El Cap in his free time for slacklining and aerial silks. His background is in technical rigging, and Sheridan helped fix lines during the filming of Dawn Wall and for Sasha DiGiulian in Canada and Spain. He’s also a hard-aid big wall climber who enjoys making record-breaking rope jumps off Yosemite’s walls.

“I just started striking up a conversation with him and asking questions. And one day, he’s like, ‘Hey, I need help going up on this wall. Do you know how to ascend ropes?’ I didn’t, but I lied to him. I was like, yeah, dude, of course.”

After the meeting, Olsen went online to see what tools were needed to ascend ropes. He walked to the Mountain Shop and bought daisy chains, aiders, and ascenders.

The next thing he knew, Olsen was carrying a heavy load up to 2,000 foot Middle Cathedral to help take photos of a new line Kevin Jorgeson was eying. Olsen, who’d only been climbing for one year, hadn’t seen Dawn Wall or even heard of Jorgeson.

Jorgeson’s route ended up not going, and he switched to High Cathedral Spire, which turned into a new 1,200-foot 5.13d called Blue Collar.

Olsen says, “I would work all day and get off work at 10 p.m. I’d meet up with Ryan at Huff; we’d get in his van and drive over to the Cathedral Spires, and we’d be on that wall all night climbing or cleaning the route or putting in bolts. At 3 or 4 a.m., we’d go back home, get a couple of hours of sleep, and return to work. We did that for weeks. It was crazy. I don’t know how we had the energy to do it.”

I reported on this climb for Men’s Journal. It reads: Two and a half years, multiple climbing partners, and chossy rock didn’t stop the co-star in Dawn Wall from completing his historic one-day climb. Olsen worked on the rigging team to help produce this film:

After his success on Higher Cathedral Spire, Olsen says, “I suddenly fell deep into the whole climbing world and got to like to meet cool climbers like Kevin and Sasha DiGiulian.” Under Sheridan’s tutelage, Olsen didn’t let his fear of heights get in the way of suspending himself on the precipice of Yosemite’s steepest walls and filming his crew leaping off the edge. “I was put on these projects, helping rig and take photos and videos. It’s pretty amazing.”

Today, when Olsen isn’t busy filming with Sheridan, he captures bouldering, cragging, and slacklining throughout the Park and travels internationally.

Sleeping over the Void in the Canadian Rockies

In 2019, Olsen, Sheridan, and his partner Priscilla (Prilla) Mewborne headed north from Yosemite to rig lines and captured DiGiulian on her quest to free three 5.14 alpine sport routes established by Sonnie Trotter. Low on time, Olsen could only shoot two of the three walls, Mount Yamnuska and Mount Louis.

He told me a story of an epic bivy he had on the way to film Sasha climbing The Shining Uncut on Mount Louis.

To get ropes in place for filming, Olsen, Prilla, and Ryan climbed up Mount Louis above Banff via a route they reconned would take one day for fast parties. But they were weighted down with heavy static lines and camera gear, so they required two days, which meant breaking it up. They aimed for a comfy, safe ledge but never found it, so they huddled on the side of the wall at one of the most exposed sections of rock they encountered. To this day, it was the worst night he’d spent out in the open.

“It was like the most heinous ledge ever,” Olsen says. “This thing was so tiny, falling apart and sharp.” Olsen believes he could be on a boat-sized block that could just come off at any moment.

In the dark, wrapped in sleeping bags, the team eked all the security they could from a web of slings clipped to various cams placed around them with a thousand-foot drop below. “We had a spider web of gear going everywhere just to be safe. Wish we had a bolt.”

But their perseverance paid off. The next day, with bags under their eyes from a restless night, the trio successfully rigged the lines and filmed Sasha climbing into the night to send the 13 pitch 5.14.

After capturing her send and safely on the top of a 2,682-meter wall, “I gave her a fist bump on the top,” he says.

Photographing Aerialists

After traveling to Canada, Olsen continued capturing Sheridan and his friends highlining at Taft Point and Cathedral Gully and leaping off Yosemite’s walls. Once, he helped capture Sheridan’s leap off the 700-foot Rostrum, even handing him his GoPro 360 and stitching the footage together so Sheridan could capture this heart-fluttering scene:

In 2021, Olsen was supposed to capture Sheridan’s record-breaking Leaning Tower jump, a homage to the late Dan Osman, but he couldn’t make it because he broke his hand while climbing with DiGiulian. He was leading a dirty hand crack at the Cookie Cliff when his feet slipped, and his weight jolted onto his hand in the crack, snapping it in two places. He tried to jug ropes up Leaning Tower, but it was too painful, so instead, he watched from the base as his friends flung themselves off the wall.

“It’s dangerous,” he says. “These climbs and rigging, you know, rockfall could happen, or something could go very wrong, and someone could die or get hurt. They’re pushing the limits. However, it’s cool to capture when it all comes together.”

To learn more about Olsen, check out his Instagram page.